Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Dying was trying in the early days of the Peninsula

Pioneer life on the greater Gig Harbor Peninsula was not easy, and death was no picnic either. There were no funeral homes, undertakers, or even cemeteries, leaving every aspect of death to family members, friends, or both. The demise of three early residents illustrates the process of death and burial on the early Peninsula, and the beginning of progress toward a more developed approach to both.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

1890

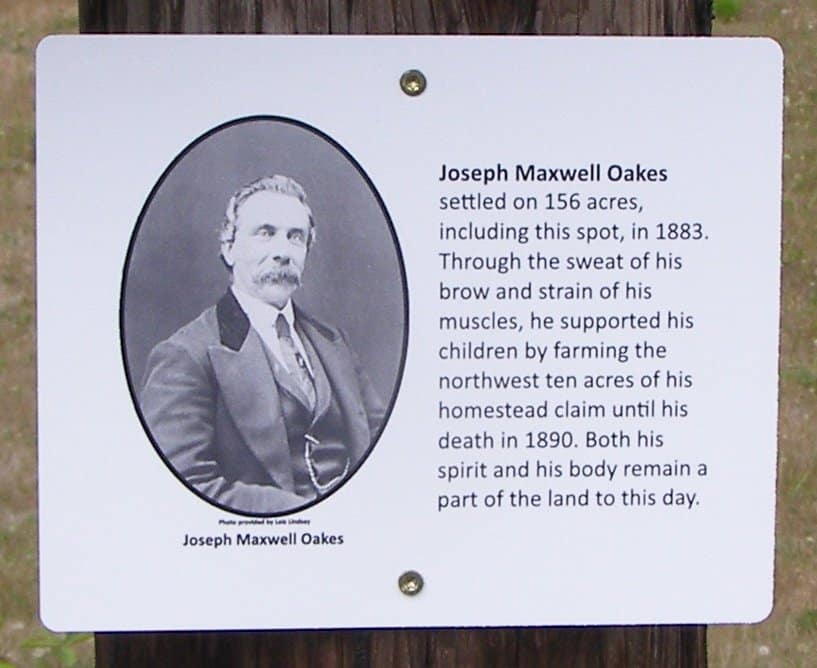

Joseph Oakes had carved out a homestead from the old-growth forest in Rosedale in the several years following his filing of a land claim in 1883. He was among the first to both settle that part of the Peninsula, and to die there. When he passed away from some kind of respiratory problem two days before Christmas in 1890, his immediate family consisted of himself and two minor children, Blanche, 13, and Wilbur, 10. They were obviously too young to handle the burial or the estate, so others had to step in. Oakes’ probate file, provided by Angeles Oakes, the wife of a descendant, tells the tale.

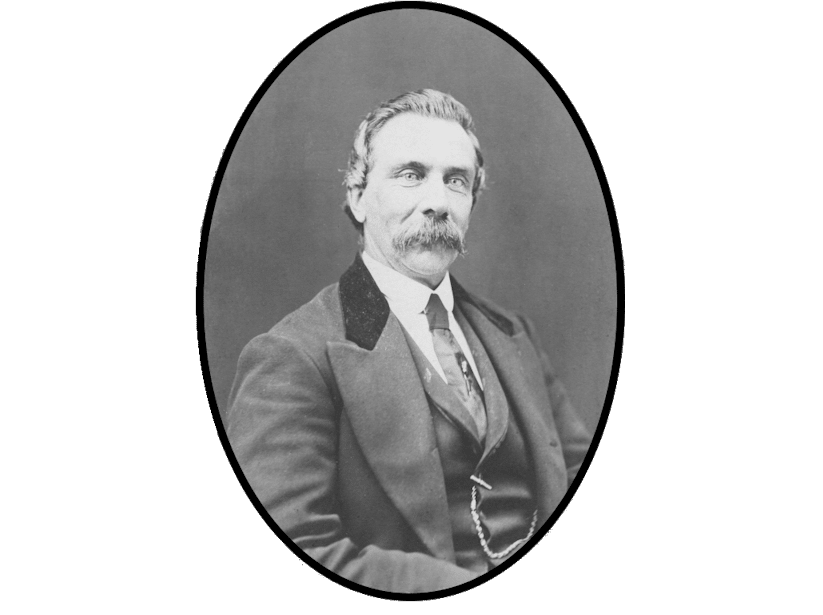

Joseph Maxwell Oakes. Photo provided by Lois Lindsey.

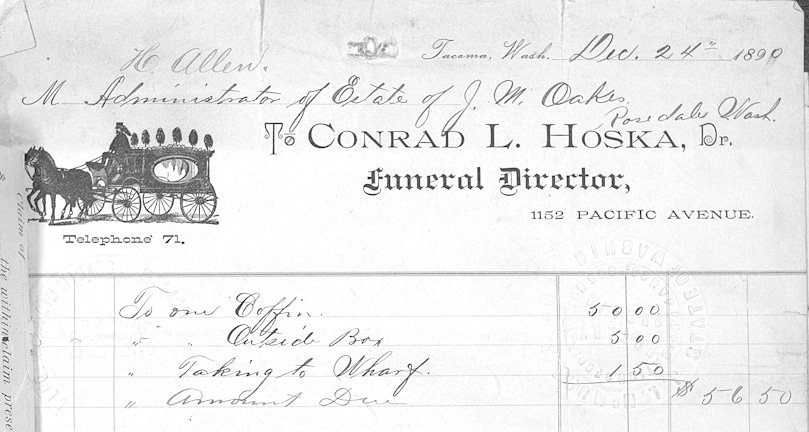

The probate file includes an invoice from Conrad Hoska, Tacoma’s second-ever undertaker. It is a bill for one coffin, one “outside box” (a shipping crate?), and a fee of $1.50 for “taking to wharf.”

What is most telling about Hoska’s bill is that it doesn’t include any undertaking services — no washing, no shaving, no dressing, no embalming, no preparation of the body whatsoever. He simply sold the estate a coffin and delivered it to a dock in downtown Tacoma to be picked up by a steamer.

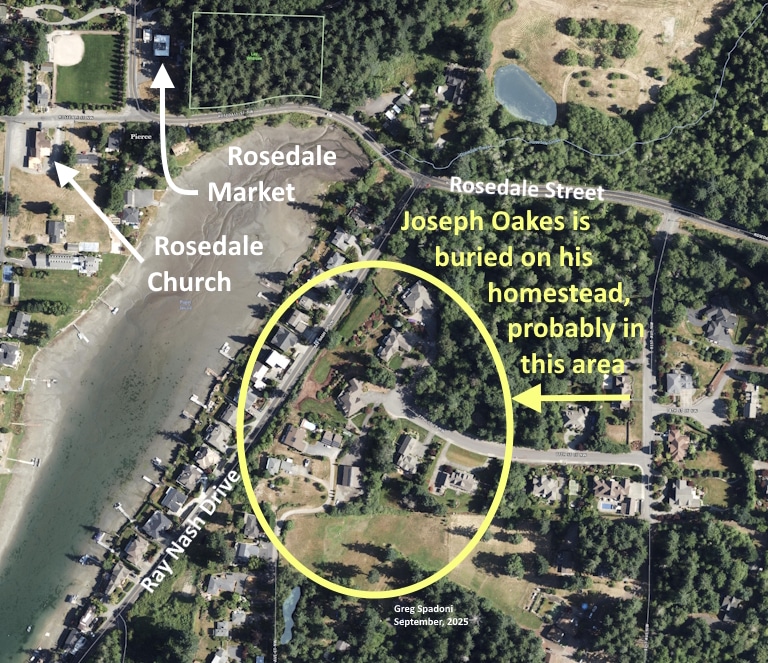

The coffin (cheaper than a casket, but at $50, still rather expensive) was delivered to Rosedale on Christmas Eve, where the body was placed inside and buried on the farm by neighbors. There was nowhere else he could’ve been buried, for in 1890 there were no graveyards in the area. The Rosedale Cemetery was still five years in the future, as was the Artondale Cemetery. Gig Harbor’s formal graveyard wasn’t officially established until August, 1891.

One of Oakes’ descendants, Lois Lindsay, confirmed in 2020 that he was indeed buried on his Rosedale homestead.

Before there were cemeteries on the Peninsula, the area’s dead were buried either in Tacoma or on their own land. How many unmarked graves on early pioneers’ properties have been lost, we’ll never know.

Precise location unknown

Exactly where on his property Joseph Oakes is buried is not known. It’s reasonable to suspect the location is somewhere near where the farmhouse stood, which was on the north one-third of the homestead. The area was fairly thoroughly explored by neighborhood kids in the last half of the 20th century, but no marker was ever found. By that time it would have long since rotted away had it been made of wood, and been completely overgrown were it made of a pile of stones. And had it been marked with large stones, there’s a very real possibility that those rocks could have been found by an oddball hermit who owned and lived on the north portion of the land from 1929 to 1961, and used for other purposes.

Joseph Oakes’ grave marker was never found by succeeding owners of his homestead or the neighborhood kids. It may have looked something like this. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Joseph Oakes is likely buried somewhere within this yellow outline. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Helping hands

As was the custom in rural America at the time, friends and neighbors relied on each other in times of crisis. Joseph Oakes’ friend and homestead proof witness Joseph Allen, 60, became the executor of the estate. Miles Hunt, 55, Joseph Whitmore, 57, and Fabius Fleming, 75, were appointed to appraise the value of Oakes’ property and personal possessions. Any of the four men, all Union Army veterans of the Civil War, or several of their grown sons, may have participated in the burial.

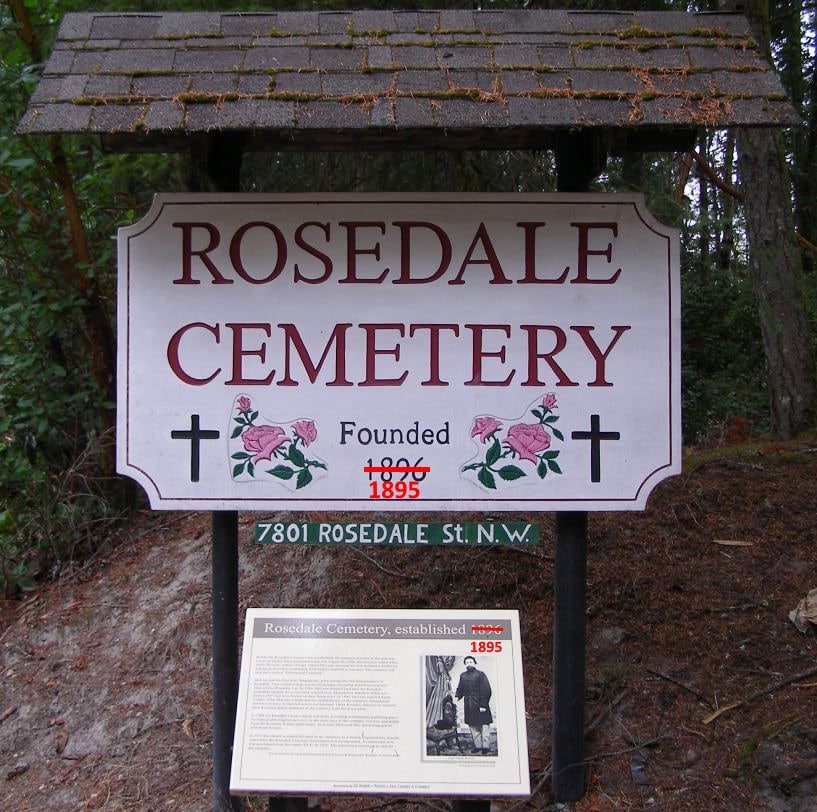

There should be no doubt that Oakes’ situation, along with a number of others, including his own, was on Daniel McLean’s mind when he donated one acre of his land to the community for the establishment of the Rosedale Cemetery in February 1895.

Lacking a local cemetery, McLean’s second wife and their child had been buried on his homestead in the late 1880s. At the beginning of 1895, in poor health, he likely saw his own death as imminent. His act of donating one acre of his homestead to the community was timely, for he died two months later, and was buried in his gift to the community.

Joseph Oakes’ situation (and others’) must’ve also been on the mind of Miles Hunt when he donated three acres for the Artondale Cemetery in March 1895. Perhaps he was also inspired by the generous act of fellow Civil War veteran Daniel McLean in neighboring Rosedale.

The creation of the Rosedale and Artondale cemeteries, one month apart in 1895, eliminated the need for burials on private property on that part of the Peninsula.

A different date and name

It is commonly accepted that the Rosedale Cemetery was established on Aug. 20, 1896. That is the date printed on the sign and plaque at the entrance of the cemetery on Rosedale Street, and is repeated elsewhere as well. That, however, is a misreading of the deed. The actual date the original one acre was granted to J. George Schindler, William Maloney, and H. Sehmel, as trustees of the then-Greenwood Cemetery, is Feb. 4, 1895. The incorrect date of Aug. 20, 1896, is simply the date the deed was recorded with Pierce County. It has no bearing on the establishment of the cemetery.

A misreading of the 1895 deed for the cemetery has resulted in an error in the date given for its creation. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Two months after the deed was executed, the site was called the Rosedale Cemetery in McLean’s funeral notice. The name Greenwood Cemetery continued to be used by the trustees who controlled the cemetery until 1924, when the Rosedale Cemetery Association was formed to take over management. But every reference found in newspaper obituary and funeral notices from 1895 to 1924 referred to it as the Rosedale Cemetery.

Restoring respect

In early 2024, Paul Spadoni restored the memory of Joseph Oakes to his homestead in Rosedale. Using text suggested by me, he created a memorial plaque and posted it on a spot that overlooks Oakes’ home site, orchard, and hay field. From that spot it’s virtually certain that we could see his grave, if only we knew where it is.

In 2024, Paul Spadoni erected a memorial to Joseph Oakes on his 1883 homestead in Rosedale. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

1892: cemeteries lose graves too

Even when cemeteries became available, there was no guarantee the resting place of the dead would be remembered. We know what happened to our next pioneer, but we don’t know how he was lost and forgotten.

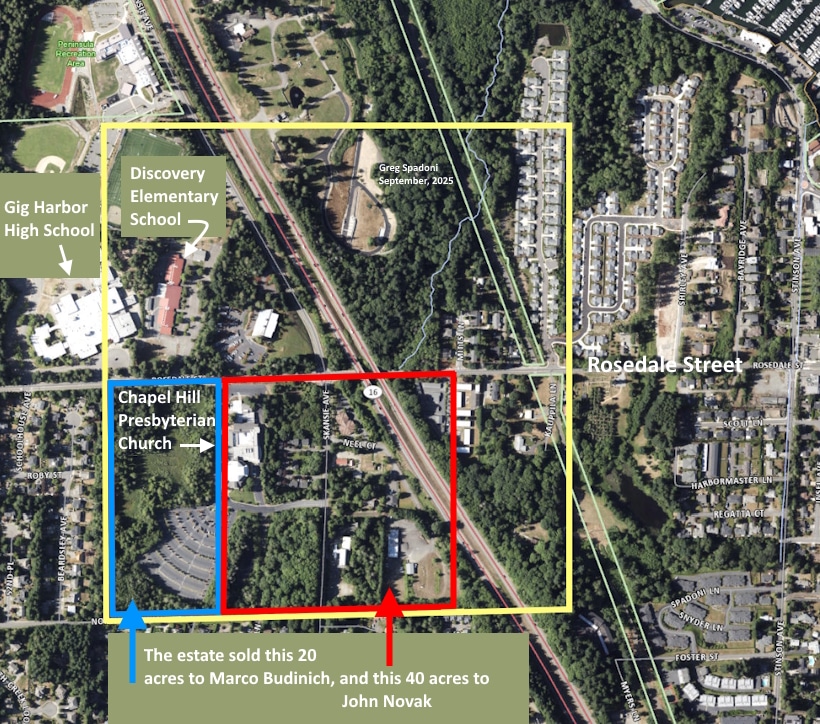

John Giblin homesteaded the 160 acres outlined in yellow. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Bachelor Irishman John Giblin, in his 20s or 30s, filed a homestead claim at Gig Harbor on Sept. 18, 1883, the same year that Joseph Oakes arrived in Rosedale. His land spanned both sides of today’s Rosedale Street, including Discovery Elementary School, part of Gig Harbor High School, and the Legacy Telecommunications building on the north side of the street; and Chapel Hill Presbyterian Church on the south side.

The property is today bisected at an angle by Highway 16. The Homestead Act required U.S. citizenship before a deed could be issued, and he became a citizen on April 21, 1890, before proving up four months later.

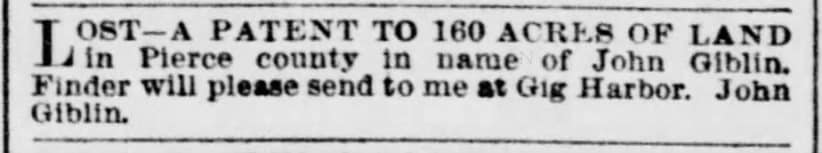

The first information found on John Giblin is the newspaper advertisement he ran in Seattle’s Post-Intelligencer in November 1891, asking for the return of the deed to his homestead, which he had lost.

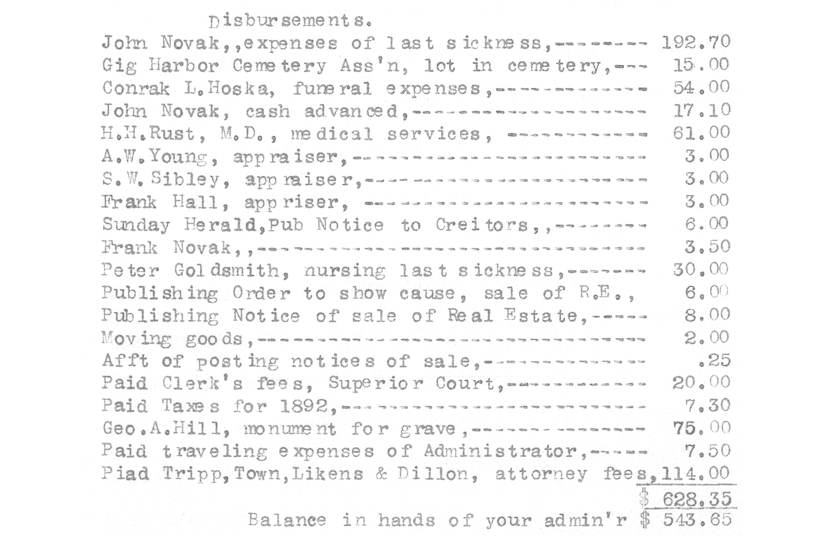

Lacking any relatives in Washington state, Giblin relied entirely on friends and neighbors for his end-of-life and after-death care. When his estate was being settled, those friends and neighbors submitted compensation claims for the care given, which may sound rather mercenary today, but was legitimate at the time. After all, some of them had expended considerable time to his benefit, and their efforts to be paid made no difference to Giblin’s heirs, who could not be found.

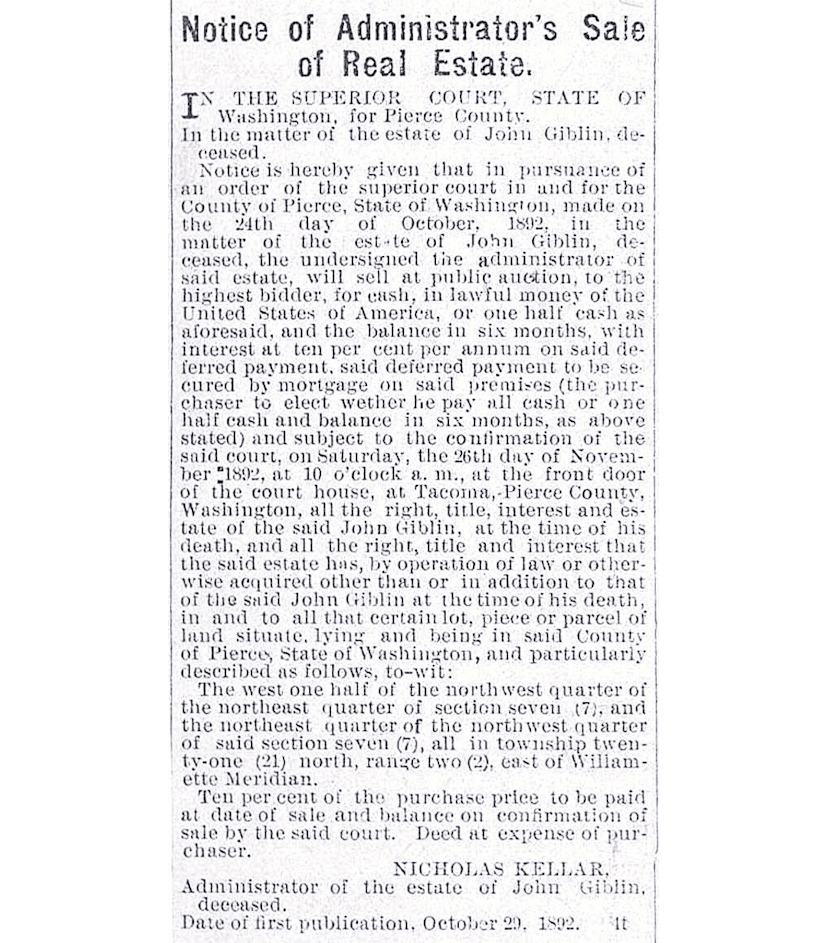

In spite of John Novak first applying for the position, Nicholas Keller, a neighbor, fellow homesteader and immigrant (from France), was appointed as administrator of Giblin’s estate.

Unlike when Joseph Oakes died in 1890, Gig Harbor did have a cemetery when Giblin passed away in 1892. His plot there was among the first few sold. Keller paid $15 out of the estate to the Gig Harbor Cemetery Association for it. He also spent $75 on a monument for the grave, from marble and granite dealer George A. Hill on Yakima Avenue in Tacoma. It was not noted in Giblin’s probate file whether the monument was marble or granite.

Both the grave and marker have been lost, for Giblin is not on the burial list of the Gig Harbor Cemetery.

With daily wages being about $2.50 for unskilled labor, seventy-five dollars (about 30 days’ wages) would’ve purchased quite an impressive monument. Perhaps it’s still there, in an overgrown section of the cemetery. If toppled over, it could be buried in the topsoil by now. A number of graves were lost on the southwest end of the cemetery when maintenance was no longer practiced there, allowing the forest to regenerate.

In any case, while John Giblin’s final resting place is in an established cemetery, his grave, like that of Joseph Oakes, has been lost.

A few Giblin estate details

Giblin, of uncertain age — somewhere between 38 and 46 — died on July 8, 1892. His probate file gives some clues to what living on the Peninsula in the 1890s was like, including how few possessions people had in those times.

The following transcription of a handwritten note states Peter Goldsmith’s request for compensation for his efforts on Giblin’s behalf:

Gig Harbor Wash. Sept. 14/92

John Giblin Deceased Due

To Peter Goldsmith

July 5th went with John Novak

to his house and cleaned it out

and took care of him chrg $14.00

July 6th 7 and 8th day and night with

boy $24.00

To watch dead body 41 hours 20.50

Total $58.50

The house referred to was Giblin’s, not Novak’s. The boy was probably Goldsmith’s 10-year-old son, Peter Jr. (The 1892 Washington census shows both Peter Goldsmiths living in Gig Harbor with no other members in the household.) There is no explanation of why Peter Goldsmith, Sr., watched Giblin’s dead body for 41 hours. Perhaps that’s how long it took to get him buried?

For an unknown reason, either the probate judge or the administrator (Keller) allowed Goldsmith only $30 of his claim.

Frank M. Novak (John Novak’s brother, not his son) went to Tacoma the day after Giblin’s death to get a coffin from Conrad Hoska, the same undertaker who had supplied the burial box of Joseph Oakes. He brought it back to Gig Harbor the same day. For his time and expenses, he charged the estate $2.50 for one day’s wages, 50 cents for passenger steamer fare for himself, and 50 cents fare for the coffin. The $3.50 total was approved in full, and he was eventually reimbursed.

Among Giblin’s personal effects was supposed to be a note of indebtedness from Joseph Dorotich, which couldn’t be found. Giblin had loaned him $200. (In 1891 Dorotich bought 20 acres of Giblin’s homestead. Perhaps the $200 note was for that purchase.) At the time of Giblin’s death, a balance of $165.70 remained to be paid. How convenient it must have been for Dorotich to not have to repay the debt. He claimed he was willing to make good on the note if only it could be found. (Not sure if that deserves a “wink, wink,” but I tend to think so. If he was so willing to make good on his debt, why didn’t he, with or without the note being found?)

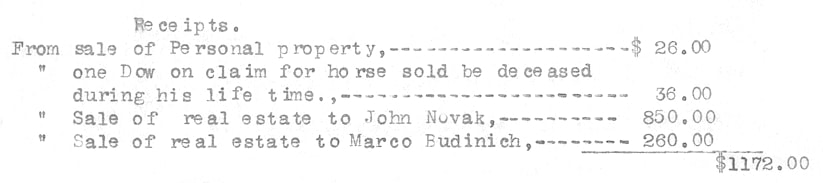

The estate was owed a balance of $36 for a horse that Giblin had sold to Edson Dow of the Midway area for $75. That debt was collected. (Edson Dow was the donator of the land upon which the Midway School was built in 1893.)

Selling Giblin’s assets

One month after Giblin’s death, Keller pointed out to the probate judge, John Beverly, that Giblin had left no cash, leaving the estate unable to pay its expenses. No bills incurred to date had been paid. He therefor requested the court’s permission to begin selling the decedent’s non-real estate assets. Keller also noted that among the assets of the estate were “some garden products and a small amount of hay … the said garden produce and hay is perishable and unless sold immediately will be lost to the estate.” The judge agreed and granted permission for selling to begin.

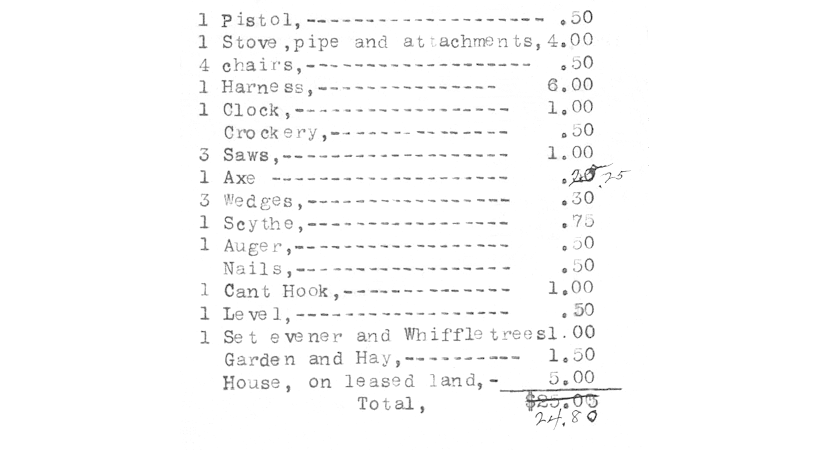

The estate sale of household goods and farm tools and products did not bring in a lot of money. Appraised in total at $28.80, they sold for $24.80. Keller itemized the results for the probate court:

The last entry in the list, a house on leased land that sold for five dollars, is not entirely clear. Keller described the house as “being owned by deceased and located on land not owned by him with privilege of moving same.”

Previous to his death, Giblin had sold off the north 80 acres and the southeast 20 acres of his original 160-acre homestead. What seems like a reasonable guess would be that the house was Giblin’s original residence on his homestead, and was located somewhere on the 100 acres he had sold. The option of moving it would make sense only if it was reasonably close to land he still owned.

At a selling price of $5, the house couldn’t have been more than a one-room shack, and a poor one at that. As we noted in Gig Harbor Now and Then column #5, the average size of settlers’ houses on Military Reservation No. 23 at Point Evans in 1916 was just 215 square feet. One-third of them were considerably smaller than that. So, many houses in those times were usually not what we think of today. They were very small, very simple shelter; nothing more. That’s why its furnishings, as listed in the asset sale, were merely a stove and four chairs, plus a bed that had no value.

Unsold remainders

Keller also noted the items that didn’t sell, saying, “the following named articles your administrator has been unable to sell and the same are unsalable and practically valueless: 1 Bed stead and springs; 1 axe, 1 mattress, 1 Pr shears, 1 Rake, 1 Square, 1 wheel Borrow [sic], 1 Bush [brush] Hook, 1 Hammer, 1 Chisel, all of which are old and of no use to anyone.”

Twenty-four dollars and eighty cents wouldn’t cover even half of the cost of the coffin or monument, and not many of the lesser expenses. Giblin’s 60 acres couldn’t be sold without first determining the status of any possible heirs, leaving Keller to fend off creditors’ late notices.

Elusive heirs

John Novak said that Giblin had mentioned to him of having siblings in Chicago, Jersey City, and Ireland. Novak could recall having heard only one first name, Patsy, the brother in Jersey City, New Jersey. He could not be located.

Because no heirs to inherit the real estate could be found, Keller petitioned the court to allow him to sell the remainder of Giblin’s homestead, the only land he owned at the time of his death. Keller described the 60 acres as “unimproved with the exception of about three acres, and wholly unproductive.” The three cleared acres were in the northeast corner of the property, where Rosedale Mini-storage is today, next to Rosedale Street and Highway 16.

For sale twice

With permission granted, the 60 acres were put up for public auction on Nov. 26, 1892. The sale drew only one bid, which was determined by Keller to be insufficient, so he canceled the proceedings. As required by law, he posted notices of adjournment of the sale “in four of the most public places in Pierce County,” which were “the bulletin board in the hall of the Court House, at Tacoma … a telegraph pole on the corner of South 11th St. and Railroad St. in Tacoma … on the front of Hall’s Store at Gig Harbor,” and “on the warehouse on Burnham’s Wharf, at Gig Harbor.”

(Hall’s store was on the present-day site of Millville Pizza in the Millville neighborhood of Gig Harbor, and Burnham’s wharf was diagonally across the street from today’s Finholm’s Market on North Harborview Drive.)

The sale was rescheduled for Dec. 10, and it went well. John Novak bought the east 40 acres for $850, and Marco Budinich of Tacoma the west 20 for $260, which today includes a substantial portion of the Chapel Hill Church parking lot.

John Novak had purchased the northwest 40 acres of Giblin’s homestead in 1890 for $1,400. Around the same time, he bought the northeast quarter of the homestead. His 1892 acquisition of 40 acres from the estate gave him fully three quarters of Giblin’s property.

Final accounting

When Nicholas Keller had done all he could as the administer of the Giblin estate, he presented the probate court with a full accounting:

Among John Novak’s expenses relating to Giblin’s last sickness was 60 cents for some rope he bought from Margaret Hall “for use at funeral of John Giblin.” Could that have been for lowering the coffin into the grave?

With no survivors, the remainder of John Giblin’s estate, $543.65, went wherever such stranded money ended up in the 1890s.

Too late

In 1909 a niece of John Giblin who lived in Ireland somehow made some inquiries regarding her uncle that made it to the Peninsula. The newspaper clip reporting the story said that Clarence Burnham of Gig Harbor responded with the information of Giblin’s death, many years prior.

It’s also too late to finish our story of Death & Burial on the Early Gig Harbor Peninsula. The conclusion will be posted on Oct. 6.

New business

Today’s topic of Death and Burial on the Early Peninsula had been planned for later publication, but something came up. No, it wasn’t a ghost from a grave, but that’s not too far off. Liberty Henderson and the Harbor History Museum are sponsoring local cemetery tours in October. It seemed like a logical thing to do would be to run history columns that compliment the idea of the tours.

According to several sources I’ve consulted, this year October follows September, which means those tours are next month.

If you would like to be one of the tourists (and why wouldn’t you?), here’s where you can buy tickets and find out when and where to show up.

Next time

The Oct. 6 Gig Harbor Now and Then column will pick up with the story of the demise of one of the very earliest settlers of Gig Harbor, John Farrague. Unlike Oakes and Giblin, the whereabouts of his final resting place have not been lost. His will be one of the featured graves on the Artondale Cemetery tours next month.

— Greg Spadoni, Sept. 22, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.