Community Environment Government

North Creek culvert replacement on hold for now

Editor’s note: The project will cost an estimated $9 million. An earlier version of this story contained an incorrect figure. Also, the city of Gig Harbor insists that the project is only “partially on hold,” because some work that is independent of remote site incubators can continue.

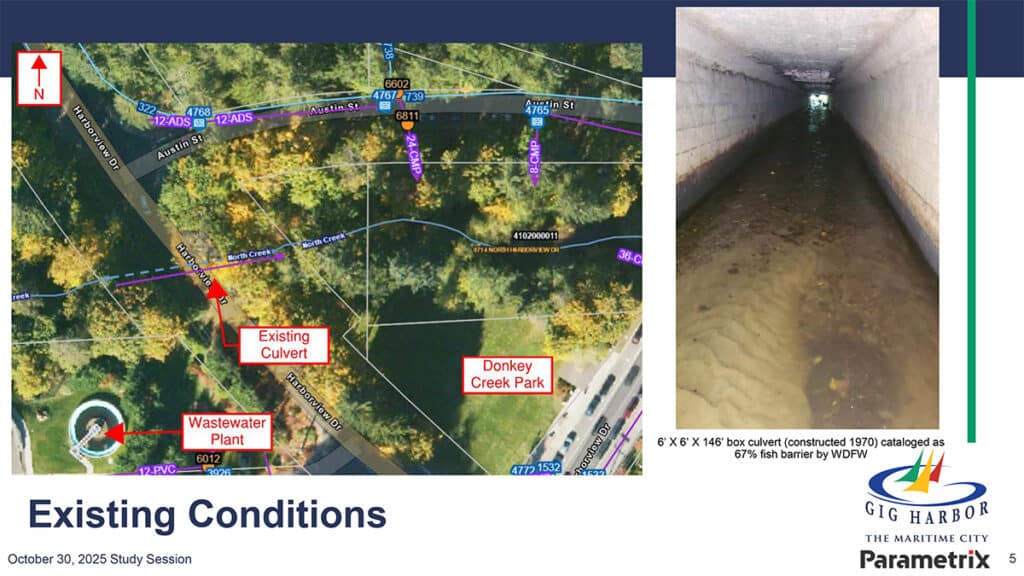

Since its construction in the 1940s, the box culvert in North Creek — also known as Donkey Creek — has been an obstacle for spawning chum salmon, who have to surmount the culvert on their passage upstream.

It’s not the only barrier these salmon face in North Creek, but it is one the city of Gig Harbor aims to tackle. The city plans to replace the culvert with a bridge, which will cost an estimated $9 million.

Public Works Director Jeff Langhelm said the culvert removal aligns with Gig Harbor’s strategic plan “to promote environmental sustainability and preserve Gig Harbor’s natural beauty.”

The box culvert is at the northwest corner of Donkey Creek Park. Photo by Vince Dice

“As such,” he continued, “the city is attempting to use best available science to restore habitat for native fish, which includes removals of fish barriers, and conserving and restoring critical areas.”

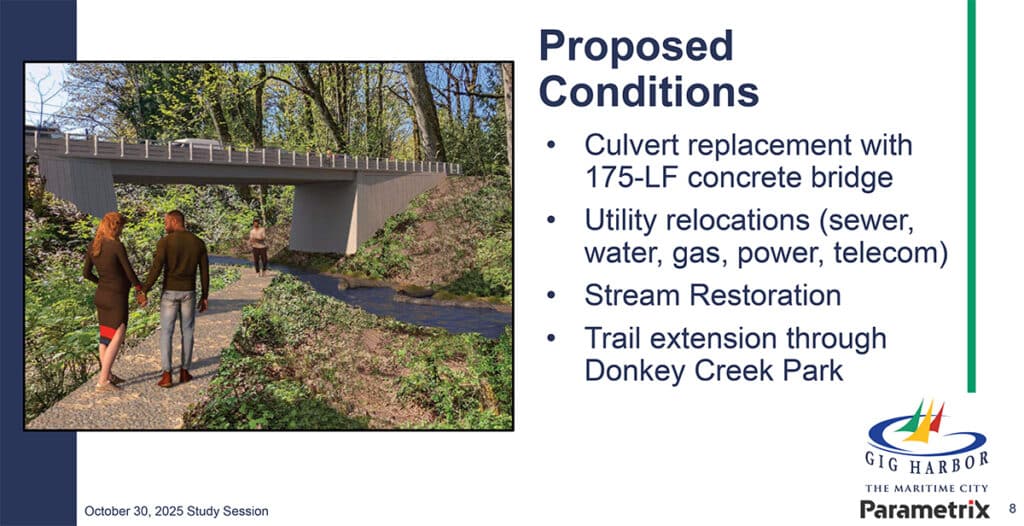

However, the project is on hold. Presenters told the Gig Harbor City Council at its Oct. 30 study session that they have paused design of the bridge because of possibly reintroducing remote site incubators (RSIs) for salmon eggs at the project site. Reintroducing RSIs could affect bridge design, timeline and cost, because the incubators need upgrades and require additional or new permitting work.

The Gig Harbor Commercial Fishermen’s Civic Club, which operates and maintains the incubators, wants them to remain. Most of the council appeared to favor including the incubators.

Culvert replacement

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) classified the culvert as a less severe partial barrier, or 67% passable for fish. The 175-linear foot concrete bridge with which the city is considering replacing the culvert would make the creek 100% passable.

The city began planning the culvert replacement in 2022. It contracted with Parametrix, a Washington-based planning firm, to conduct a feasibility study and propose alternatives to the culvert. The city chose the bridge rather than a three-sided box culvert alternative.

The project was slated to cost $9 million, city senior engineer Steven Demmer said. But that estimate is based on 2023 dollars and only a partial design. The city now expects it to cost more, but Demmer didn’t say how much.

Remote site incubators

The site has remote site incubators for salmon eggs, but the Gig Harbor Commercial Fishermen’s Civic Club hasn’t operated them since before 2020.

Steve Seville, the director of salmon recovery at Parametrix, explained that building a bridge will change water flow by restoring the stream and floodplain. This means that “there’s going to be a lot of flow moving through there without the culvert blocking it, and so we need to find a new location for the RSI.”

The process is fairly complicated. It may involve, among other things, an entirely new permitting process and handling water rights questions.

Seville presented a new, more compact vertical incubator design, which upgrades the quality of the incubators and their security. The new design would require water diversion as well as an electrical supply.

The new incubator design would also be mobile. It could be moved into the park from October through May and removed when not in use. He said the city would store the incubator in a shaded structure at the park.

Remote site incubators in North Creek at Donkey Creek Park. Photo by Vince Dice

More expensive

He said that they have not yet figured out the exact cost to upgrade the incubators, but gave a few estimated numbers.

The incubator design details would cost an extra $75,000, while permitting would fall somewhere between $30,000 and $150,000, depending on whether they would have to restart the permitting process. The new incubator materials would cost $125,000, while construction would cost an estimated $200,000. Seville did not have a maintenance cost for the incubators.

Including the incubators in the overall culvert removal and bridge installation could set the project back about two years, Seville said. This is because they would have to modify the permit submittal and overall design. This involves engaging an incubator supplier, negotiating with WDFW, and managing a water rights changeover with the DOE.

Without including incubators, however, they are on target to release a final design package by early spring 2026.

Seville said that while remote incubators are “a great low-tech” alternative to a massive, formal hatchery, the operation of these incubators relies on the available salmon broodstock from WDFW hatcheries. That broodstock may have limited genetic diversity.

“Whatever WDFW is able to provide kind of dictates the efficacy of the propagation of the species, and local and wild genetics are more and more preferred,” Seville said. “Hatchery eggs that you’re getting from the hatchery are less desirable unless they have specific genetics.”

A page from a city of Gig Harbor presentation about the Donkey Creek culvert project.

Professional opinion

He also said that water quality can affect the incubators, but that Gig Harbor is “doing a great job of protecting the watershed, and the water quality in North Creek is really pretty good, so that … is a great source, and so that’s positive.”

However, no one is formally monitoring the operation of the current incubators, he said. The effectiveness of incubators is crucial to justify investing in them.

“Considering potential monitoring data year over year to show how that investment is being successful is something to keep in mind, and not a lot of work is done in that capacity right now,” he said.

He also pointed out that, thanks to the city’s protection of the local watershed, the area is beneficial to other kinds of salmonids, not just chum salmon.

“The running and the timing of the facility should be considered against other species that are in Puget Sound and could access and may have accessed the stream in the past, including coho and other species,” he said. “It’s not just a chum stream, although primarily that’s what’s there. The city has the potential to consider larger benefits with not just the RSI. So I’d say that it’s been a great facility, and considering moving forward, there’s a lot to kind of absorb to figure out if it’s worth the investment.”

Public opinion

The Fisherman’s Club has repeatedly told the city it would like the incubators to remain at the site. The club committed to operating and maintaining the incubators through 2040.

The current incubator barrels can hold about a million eggs, which WDFW has provided when the incubators were running. Langhelm said that the city has discussed with the Fisherman’s Club whether half that number would be acceptable, as a way to lower costs.

A few members of the club attended the study session and spoke in favor of the incubators.

Tom Lorovich acknowledged that “it’s a difficult decision to make to spend that kind of money to keep this going.” He added that the club is open to downsizing the number to decrease cost. However, because the state would not let them put eggs into the incubators starting in 2020, due to the onset of the COVID pandemic, “that’s why you see everything looks like it’s in disrepair, because we were unable to get eggs for three years.”

He also floated the idea of a different kind of incubator that could cost less.

Club member Greg Lorovich said that the project “is no benefit to fishermen,” and that it was instead an historical site that the club would like to see continued.

Opposition

However, not everyone supports the incubators.

Langhelm cited the Wild Fish Conservancy’s 2024 opinion letter to Gig Harbor Now that pointed to the conservancy’s 2018 survey work. The watershed is healthy and connected with streamside forest, and has the potential to naturally support a variety of fish populations, the conservancy wrote. It’s not a “glorified drainage ditch,” they said.

However, the incubators have neither proven to be sustainable nor beneficial, the conservancy wrote. The incubators may have also negatively impacted wild salmon.

“To our knowledge, there are no monitoring data to show the North Creek chum hatchery incubator benefits fisheries; and no data describing the extent to which the program’s hatchery chum salmon stray into other watersheds that support wild chum salmon, like nearby Crescent Creek,” the conservancy wrote. “As WDFW has reported, when hatchery fish spawn with wild fish, it harms wild fish populations — one of many negative unintended consequences of often well-intentioned hatchery programs.”

Langhelm said that Harbor WildWatch, the city’s educational nonprofit focusing on local water health and biodiversity, has not taken a stance on the incubators.

A page from a city of Gig Harbor presentation about the Donkey Creek culvert project.

Tribe’s view

The Puyallup Tribe also does not have an opinion on the incubators, Langhelm said. However, it did note that a historical tribal village located there thrived because “of the fish and the life that was there at the outlet of the creek. “They wanted to acknowledge that they believe that there is sustainability of the salmon moving forward.”

“They very much look forward to and appreciate the culvert replacement project, but as far as the RSIs go, they don’t have an opinion one way or the other as to whether or not the RSIs stay,” Langhelm said.

He also said that, despite providing salmon eggs for the incubators, WDFW does not rely on them to support the overall mission to increase salmon numbers in local waters. The department is also neutral about the incubators.

Council opinion

Most of the council appeared to support continuing the incubator project, but wanted to hear about other incubator options that may be cheaper than the one Parametrix presented.

Only Councilmember Roger Henderson said he did not support it, because the benefits did not seem to justify the extra cost and extended timeline. He said that the money spent on the addition of the incubators could go towards educational programs other than those attached to an incubator program.

“We are not giving the native population a chance to re-establish — and they do,” Henderson said. “Once we end up daylighting this culvert, there will be natives coming back and maybe some chum as well. So I’m not sure I can support this. I don’t believe the city is obligated to put it back or to pay for it.”

Rodenberg appeared to suggest that Parametrix only explored the most expensive options. He said the company has “a monetary interest” and “are making it as difficult as they can.” He said that he would like to hear Tom Lorovich’s idea that could be less expensive.

“I would much rather trust some guys that have been standing in that stream with water up to their knees since they were six years old, than somebody that lives 50 miles away that doesn’t know about our particular water,” he said.

Culvert impact

Rodenberg alleged that the Puyallup Tribe fished out the creek in the 1960s. He did not acknowledge that installation of the culvert in the 1940s caused a major disruption to migrating fish, just as other culverts around the state had done. This is why a state court ordered culverts removed.

The city’s own webpage regarding the project states that “prior to the 1920s, the North Creek basin was mostly free flowing (did not flow through man-made structures). However, as the local vehicle transportation system began to develop, the state of Washington and Pierce County placed roadways over North Creek and installed culverts and one bridge over North Creek.”

“Eventually the bridge was replaced with a culvert. While these culverts were maintained to allow the [creek] to flow through them, the culverts either partially or fully blocked the migration of anadromous fish,” the site reads. “Until the early [1950s], North Creek … flowed freely from its headwaters to Austin Estuary and into Gig Harbor Bay. In the 1950s, much of the estuary was filled in and a series of culverts were installed to divert the [creek] through town.”

Langhelm also pointed out that the Puyallup Tribe said that the creek had been a food source for them prior to European settlement.

“That culvert was installed in the ‘40s,” Langhelm said. “So we’re not talking about any of our lifetime [having] seen that site in its natural state.”