Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The Gig Harbor brickyard

Presenting a story of history in text takes different forms, depending upon the target audience. For Gig Harbor Now and Then, the audience is made up of casual readers. They are primarily interested in the overall story, without the minutia of specific attribution of facts, or how those facts were obtained.

Other audiences — for example the staff at the Harbor History Museum — require thorough documentation, as it’s critical to be sure that the information is correct, especially when it proves long-accepted facts to be false.

Documentation allows others to confirm the sources of the information. It also provides a starting point for anyone wanting to pursue a subject further than it has previously been explored, or follow a different branch of the same story.

I always use footnotes rather than endnotes to list the documentation of a story. When I adapt one of my previously written pieces for a Gig Harbor Now and Then column, I always strip out the footnotes, as they are of no interest to the casual reader, and can sometimes be distracting. I’ll often try to add some of the documentation into the main body of the text, mostly newspaper citations, but it’s never complete. For one thing, I almost always leave out the page number. (Although many early newspapers, including Gig Harbor’s weekly, The Peninsula Gateway, didn’t have page numbers for many years. It started numbering its pages in the 1950s.)

In today’s story, however, I’m going to leave the footnotes in as an example of what the documentation looks like.

Footnotes are normally at the bottom of each page, but since there are no page divisions on this website, I have moved them to the end of each of this story’s three parts (Part 1 today, Part 2 on Jan. 26, and Part 3 on Feb. 9). That makes them sort of hybrid footnotes/endnotes. While that placement doesn’t fully convey how distracting footnotes can be, it does show that I don’t make this stuff up. And sometimes readers do wonder where all the information comes from. (Footnotes are in parentheses and italicized.)

One category of sources I almost never use is previously written stories of local history. They commonly repeat mistakes of others before them. That serves only to mislead or confuse, preventing an accurate understanding of Peninsula history.

Instead, I rely on original sources, which include newspapers, magazines, land deeds, affidavits, city and telephone directories, immigration and citizenship documents, censuses, legal filings, courtroom testimony, diaries, letters, and photographs. It’s not the easy way; it’s the only way.

The following is a condensed version of The Gig Harbor Clay Company of Gig Harbor, Copyright 2019 by Greg Spadoni.

The Gig Harbor Clay Company, Part 1

Albert Jonsoni took an unusual route to America. Born in the northern Italian town of Belluno (or Bellino) in 1858 (1) with the name Filiberto Teobaldo Jonsoni, (2) he lived in Venice before moving to South Africa, which is probably where he changed his first name. He married a woman fifteen years his junior, Rose Ann Britton, from Australia. (3)

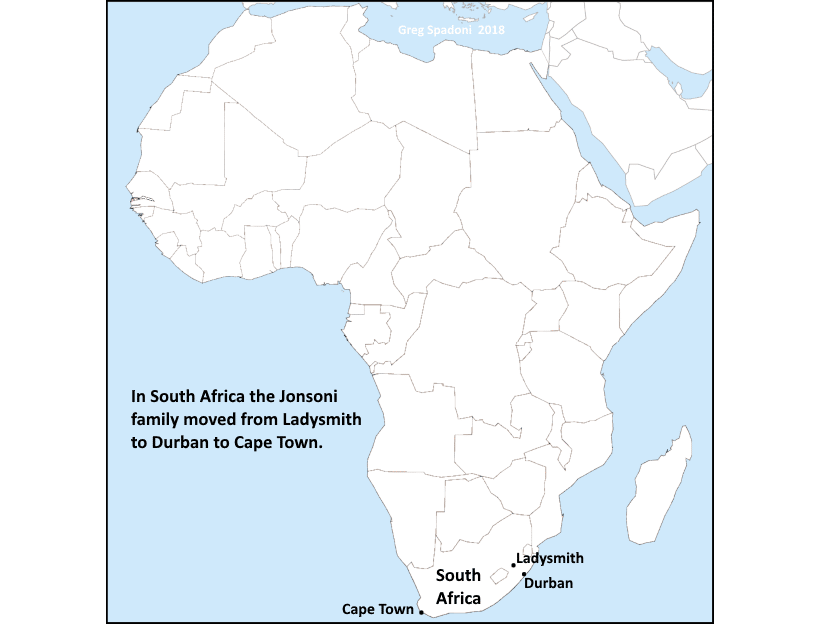

Their first two children were born in the British colony of Natal, in southeast Africa (today a province of the Republic of South Africa): Violet in Ladysmith, (4) and Albert Jr. in Durban. (5) The family then moved to Cape Town.

The Jonsoni family in South Africa in 1900. Photo provided by Dr. Randall McIntyre of Austin, Texas.

The Jonsonis lived in Ladysmith and Durban before ending up in Cape Town.

Jonsoni was primarily a building contractor, though he had a variety of other business interests. In at least one of those interests, he partnered with another man from Italy, Luigi Gasloli.

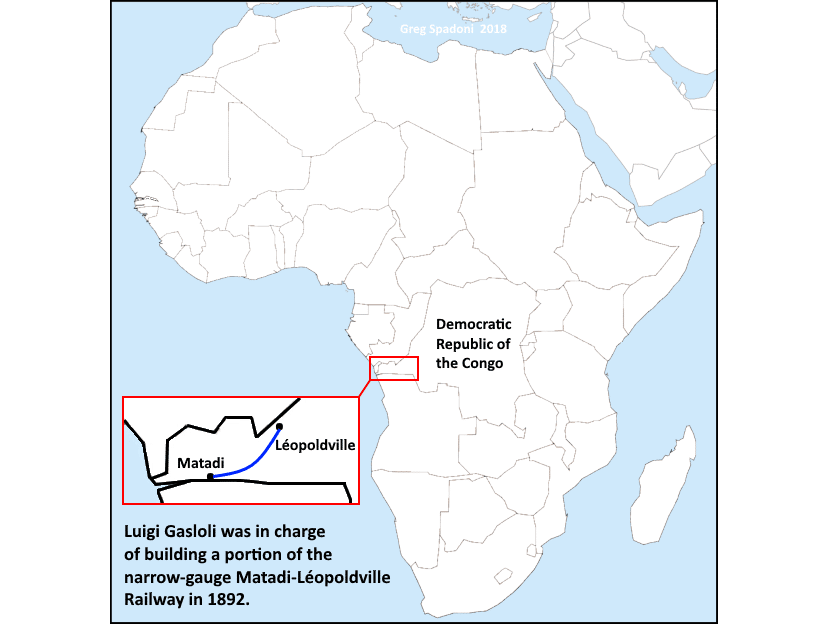

Luigi Gasloli was born in the town of Cuggiono in northern Italy in 1866. (6) He, like Jonsoni, was a contractor. But before arriving in South Africa, he spent some time in the central part of the continent. He was responsible for the construction of one of the first sections of the narrow-gauge Matadi-Léopoldville Railway in the Congo Free State. (7) Due mostly to disease, the building of the railroad was very dangerous work, costing just short of 2,000 lives before the line was completed in 1898. It is still in use today.

The railroad Luigi Gasloli helped build in the Congo is still in use today.

A South African business

By the late 1890s Gasloli was living in Salt River, a suburb of Cape Town, South Africa. Salt River was the industrial center of the area, an appropriate place for an industrious young man. Among other projects, he, along with Albert Jonsoni, assembled some kind of machinery or other setup having to do with the concrete industry. On May 20, 1898, they sold the project to the Salt River Cement Works for 5,000 shares of the acquiring company. (8) It was restricted stock, meaning they were not allowed to sell it to anyone outside the company for a specified period of time, in this case three years. (9)

At the end of the three-year restriction period, the stockholders of the Salt River Cement Works voted to liquidate the company. (10) Gasloli believed the liquidation was designed to sell the components of the company to the other stockholders at very low prices, thereby substantially reducing the value of his share of the company, if not cutting him out entirely. He filed suit against them and they agreed on a settlement. The company paid him 2,500 English pounds for his 2,500 shares. (11) That was equivalent to U.S. $12,175 (about $464,000 in 2026).

Louis (Luigi) Gasloi as an older man. Photo provided by Nina Kornell.

Other continents

In 1904, Gasloli left Cape Town for America, via Southampton, England. (12) He, his wife Nina (who most often used her middle name, Martina), and their first child went to Herrin, Illinois, where their American contact, Mrs. Rosa Moroni, lived. (13) (Born in the same town as Gasloli, Rosa, whose maiden name was Berra, may have been a relative.) Within a year or so Luigi went to China for work, leaving his wife and child in the States. He returned in 1906, (14) settling with his family in Tacoma.

From South Africa to Gig Harbor

The Jonsoni family stayed in South Africa after the Gaslolis moved to the United States. Albert renounced his Italian citizenship and became a British subject, (15) obviously intending to remain in the colony. Their stay on the continent ended, however, after their lives took a tragic turn in December of 1906. Their 16-year-old daughter, Violet, died in a kitchen fire. Their overwhelming grief would not let them continue to live in South Africa. To escape constant reminders of their daughter in Cape Town, they traveled to Switzerland, Italy, and England. Ultimately, they decided to move to America.

Leaving Southampton, England, on March 30, 1907, Albert, Rose, Albert Junior, Ruby and Sybil Jonsoni crossed the Atlantic Ocean on the steamer S.S. New York, landing at New York. (16) They had plans to meet up with their old friends, the Gaslolis, in Tacoma. (17)

Soon after the Jonsonis arrived in Tacoma by railroad, Albert decided he was going to become a manufacturer of clay products.

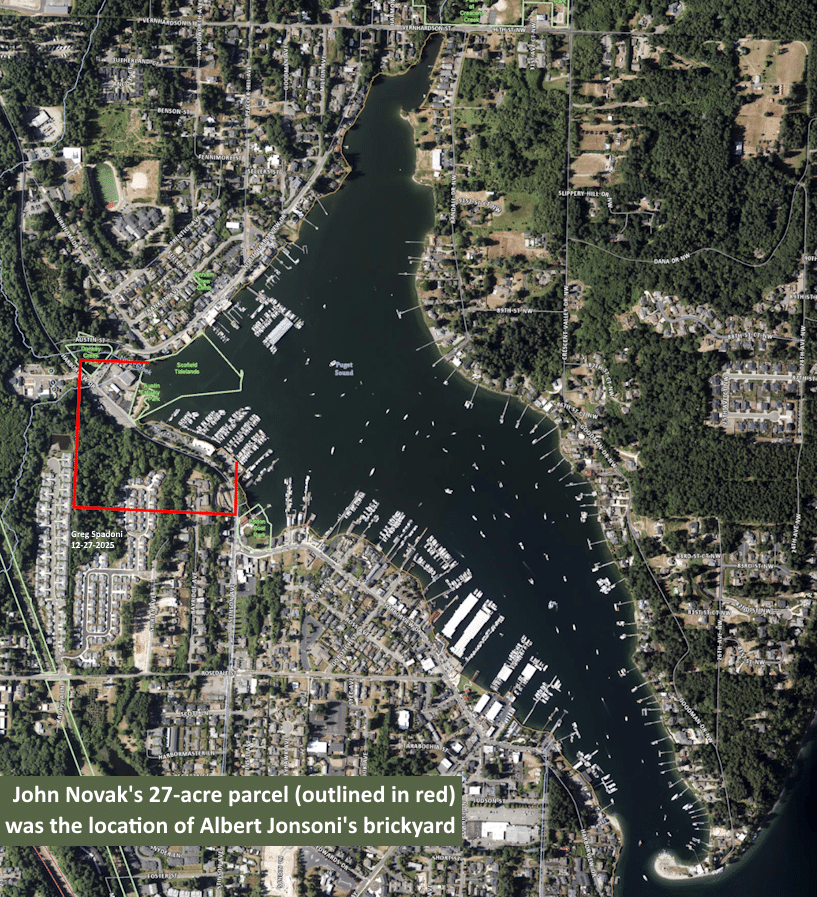

It was commonly known in south Puget Sound that John Novak was determined to see the Gig Harbor-Millville area grow. (18) He controlled a piece of waterfront land in Gig Harbor where his brother-in-law, Jack Cosgrove, used to live. (19) It had an entire hill of clay on it. Jonsoni somehow became connected with Novak and leased a portion of that clay hill. (20)

Novak was uncharacteristically generous to Jonsoni in the land lease for the brick plant. He required no money up front, no monthly or annual lease payments, and no minimum duration of the agreement. The contract obligated Novak for 10 years, yet Jonsoni was free to walk away from the land at any time without penalty or obligation, other than any and all broken brick remaining on the site becoming the property of John Novak. Compensation to Novak consisted entirely of fees based on the plant’s production. That allowed Jonsoni to apply his initial capital entirely to the plant.

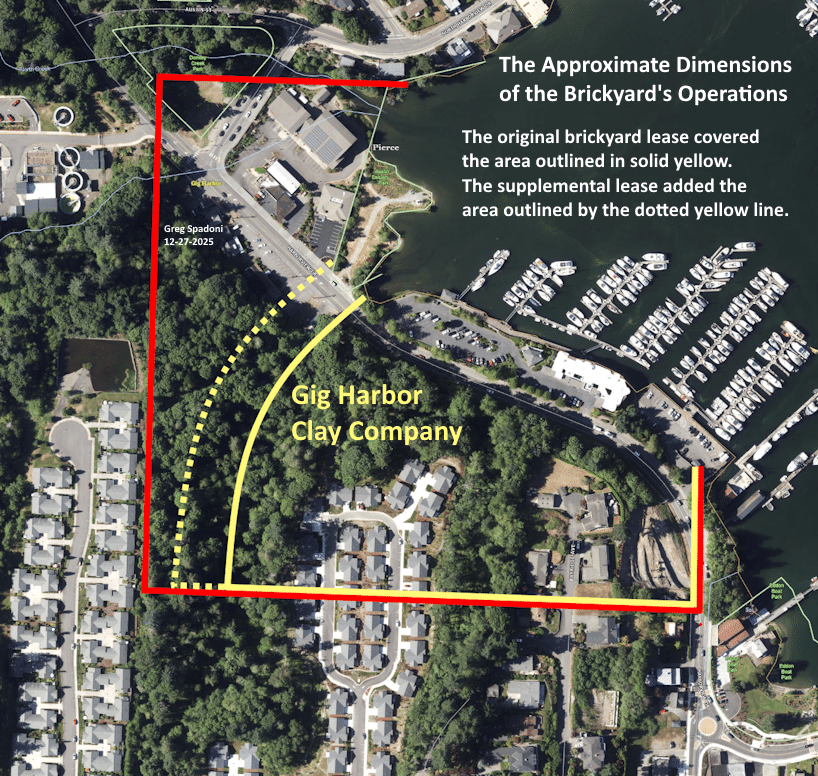

This 27-acre parcel was only one of John Novak’s many land holdings in Gig Harbor. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The lease contract allowed Jonsoni almost free rein over more than half of the dry land in the Northeast Quarter of the Southeast Quarter of Section 6.

The Gig Harbor Clay Co. did not take up John Novak’s entire 27-acre parcel. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Jonsoni was also given the right to use the water from an unnamed creek that today is piped underground, beneath Harborview Drive, between the dotted and solid yellow lines on the above map. He was restricted from damming it to the extent that it flooded neighbors’ properties without their permission.

In a line of the contract that would never be allowed today, Jonsoni was further granted the right “to dump refuse into the waters of said Gig Harbor,” although it was not something Novak had any authority to grant.

Production fees to be paid by Albert Jonsoni to John Novak were 20 cents for every 1,000 bricks and 25 cents for every 1,000 roofing tiles. Whether that was a reasonable rate is not known today.

The lease was signed by John and Josephine Novak (with their marks, as neither could write) and Albert Jonsoni on May 9, 1907, barely a month after he landed in New York. The signing of the lease was witnessed by George Novak, one of John and Josephine’s sons, and Luigi Gasloli, who had Americanized his first name by changing it to Louis.

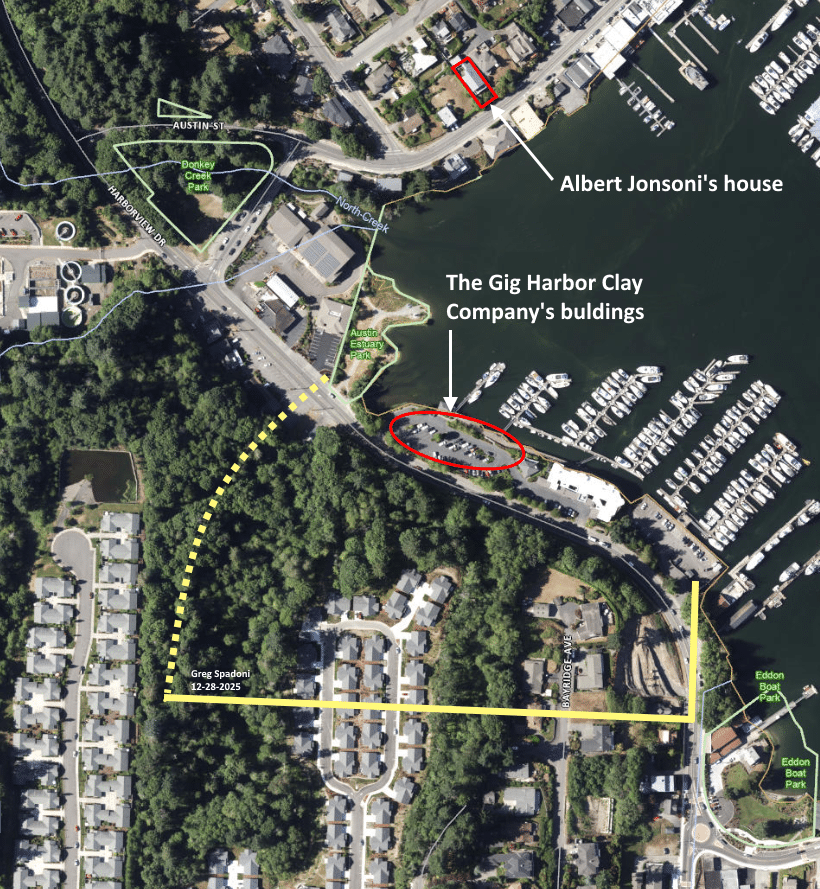

Possibly expecting to live in Tacoma, on May 17 Jonsoni bought four building lots there, (21) but never used them. On June 7, he bought a house at the north end of Gig Harbor (22) and brought his family over from Tacoma.

Albert Jonsoni’s house was straight across the northwest tip of the bay from the brickyard. His daily commute was a five-minute walk. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Satisfied that he was in America for good, on May 21, Jonsoni signed a declaration of intent to become a citizen of the U.S.A. (23)

Early expansion

As he began working on his clay brick and tile factory, Jonsoni apparently realized he needed more land for his operations. He and John Novak worked out new lease terms and signed a supplemental agreement on July 26. (24) It granted Jonsoni an additional 125 feet to the west for his brickworks, and higher payments for Novak. The new rate schedule was 25 cents per 1,000 bricks sold during the first 10 years; 30 cents per 1,000 bricks sold during the second 10 years (should Jonsoni renew the lease after the first 10 years); and for all clay used in the manufacture of any product other than brick, 15 cents per cubic yard.

Five days after signing the supplemental agreement with Novak, Jonsoni took in three partners and titled the operation the Gig Harbor Brick and Trading Company. (25)

The new partners

At the time of partnering in the brick-making business, Cassius D. Fuller, who had come to Tacoma with many other people from Albert Lea, Minnesota, in 1889, (26) was the new owner and operator of the Gig Harbor Trading Company. (27) It was a partnership with Christian O. Barness, (28) another Minnesotan who left Albert Lea for Washington in 1888. (29) They sold building materials and did plumbing and tin work. Fuller was also the Gig Harbor postmaster from 1906 to 1909.

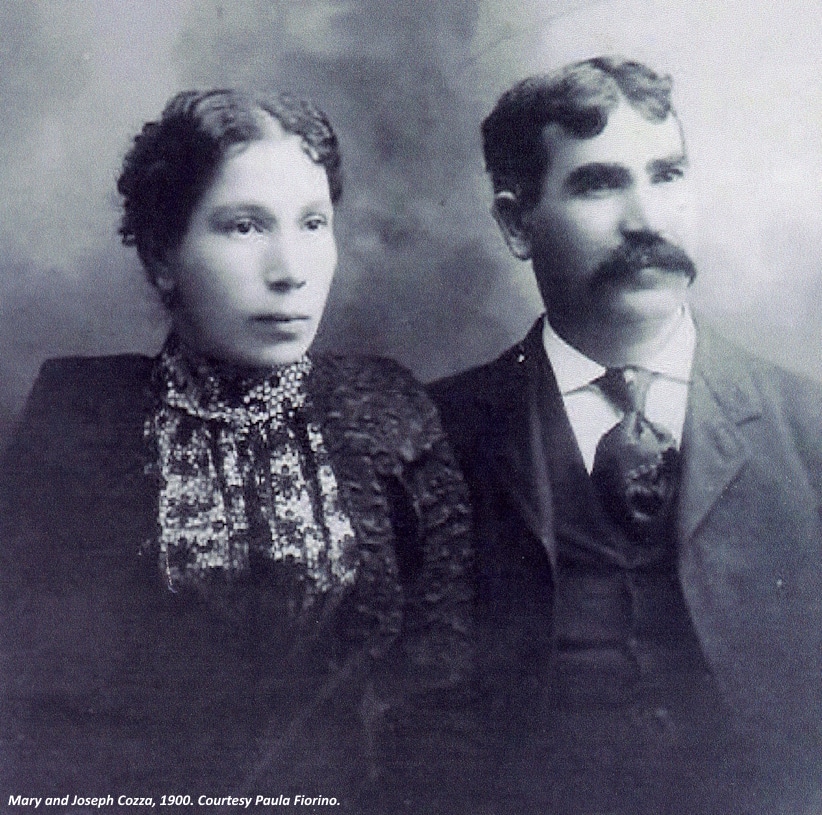

Joseph Cozza, a naturalized immigrant from Italy who changed his first name from Giuseppe when he arrived, was a veteran of several businesses in Tacoma. He ultimately focused on selling poultry, and would continue in that business during and after his participation in the brick yard.

Joseph and Mary Cozza in 1900. Joseph was an early investor in the Gig Harbor Clay Company. Photo provided by Paula Fiorino.

Louis Gasloli, who was working at a Tacoma furniture plant, once again joined his old business partner from South Africa. He, like Jonsoni, moved his family to Gig Harbor to be close to the brickyard.

Jonsoni, Gasloli, Cozza, and Fuller were the principal owners of the Gig Harbor Brick and Trading Company. Another Italian, Gaetano P. Cozza, an older brother of Joseph Cozza, later contributed money. (30)

Economic recession

In April 1907, the Puget Sound region was finishing up a full year of an unprecedented level of logging and lumber milling, spurred by the rebuilding of the San Francisco area after its devastating earthquake and fire the previous year. But by the middle of 1907, the national economy was entering a recession. Albert Jonsoni soldiered on with his brick works in spite of the economic downturn.

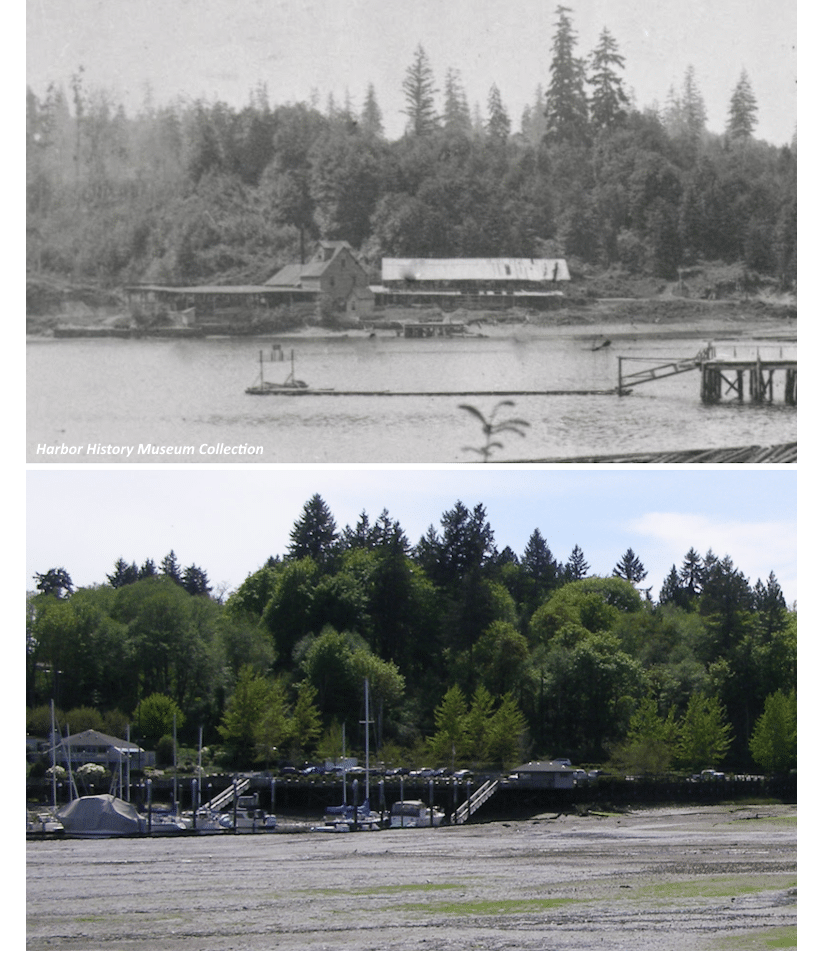

The Gig Harbor Brick and Trading Company erected buildings on the waterfront of its leased land to house materials, products, and the manufacturing machinery. To feed the works, clay was excavated at the base of the hill behind and beside the plant.

The upper picture is the only known photograph of the Gig Harbor Clay Company’s plant. The date is between late 1908 and late 1918. It looks abandoned, so may be from the upper end of that range. The lower picture shows the same site (now occupied by Murphy’s Landing marina) in 2018 from approximately the same distance and angle. Upper photo provided by the Harbor History Museum. Lower photo by Greg Spadoni.

Building the business from scratch was a major undertaking. Jonsoni was working hard on his new project and spending a lot of both his and his investors’ money. Despite the best efforts of himself and his employees, the brickyard was not manufacturing a good product. The crew struggled with poor results into 1908.

Next time

After failing to make a marketable product in 1907, Albert Jonsoni continued to work towards producing clay bricks in Gig Harbor that would sell. Just because his first year was unsuccessful didn’t mean he couldn’t turn it around in 1908.

Part 2 of The Gig Harbor Clay Company will be posted on Jan. 26.

— Greg Spadoni, January 12, 2026

Footnotes

- Albert Jonsoni’s Declaration of Intention (to become a U.S. citizen), May 21, 1907. (The handwriting is not entirely legible. It could say Belluno or Bellino, both being towns in Italy. Several other sources say Venice.)

- Note written on the back of a 1900 family photo by Sybil Jonsoni Ludlow.

- Note written on the back of a 1900 family photo by Sybil Jonsoni Ludlow.

Rose Jonsoni’s death certificate, May 31, 1957, State of Texas, State File No. 30969. - Note written on the back of a 1900 family photo by Sybil Jonsoni Ludlow.

Baptism record, South Africa, Church of the Province of South Africa, Parish Registers, 1801-2004, FamilySearch entry for Violet Rose Jonsoni, 23 Dec 1890. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6J33-9FJY : Fri Mar 08 22:51:23 UTC 2024) - Note written on the back of a 1900 family photo by Sybil Jonsoni Ludlow.

- The year of birth was found on Louis Gasloli’s 1940 death certificate; the place is given on many citizen and immigration documents.

- L’esplorazione commerciale e l’esploratore viaggi e geografia commerciale, page 346.

- Annuario scientifico e industriale by Augusto Righi, 1893, page 443.

- Cape Times Law Reports of All Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the Cape of Good Hope, Oct., Nov., Dec., 1901, reported by J. D. Shell, K. C., page 478.

- Cape Times Law Reports of All Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the Cape of Good Hope, Oct., Nov., Dec., 1901, reported by J. D. Shell, K. C., page 478.

- Cape Times Law Reports of All Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the Cape of Good Hope, Oct., Nov., Dec., 1901, reported by J. D. Shell, K. C., page 478.

- Cape Times Law Reports of All Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of the Cape of Good Hope, Oct., Nov., Dec., 1901, reported by J. D. Shell, K. C., page 478.

- Passenger manifest, S.S. Philadelphia, arrived at New York Oct. 1, 1904.

- Passenger manifest, S.S. Philadelphia, arrived at New York Oct. 1, 1904.

- Passenger manifest, the Kanagawa Maru, sailed from Shanghai, China on May 6, 1906, arrived in Seattle June 1, 1906 (Nina Gasloli, as the relative Luigi Gasloli would be meeting in the U.S., is listed as Martina, which was her middle name).

National Archives of South Africa, Database: Cape Town Archives Repository, Application for letters of Naturalization, Albert Jonsoni, 1904.

Albert Jonsoni’s Declaration of Intention (to become a U.S. citizen) dated May 21, 1907, shows that he had completed his naturalization in South Africa, as he was by then a British subject. - Passenger manifest, S.S. New York, April, 1907.

- Passenger manifest, S.S. New York, April, 1907.

- The Morning Olympian, September 15, 1904, “John Novack [sic] is anxious that a mill be located at Gig Harbor, and as an inducement, has offered to donate a site at the head of the bay.”

- John Novak did not receive legal title to the property until one full year later, on May 13, 1908. (Jack Cosgrove never owned it.)

- Lease Agreement, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 244439, May 7, 1907, Grantors John Novak and Josephine Novak, Grantee Albert Jonsoni.

- Deed, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 240034, May 17, 1907, Grantee Albert Jonsoni.

- Deed, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 241270, June 7, 1907, Grantee Albert Jonsoni.

- Albert Jonsoni’s Declaration of Intention (to become a U.S. citizen), filed in Pierce County Superior Court May 21, 1907.

- Supplemental Lease Agreement, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 244785, July 26, 1907, Grantors John Novak and Josephine Novak, Grantee Albert Jonsoni.

- Agreement, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 275591, September 22, 1908, parties of the first part Albert Jonsoni, Rose Annie Jonsoni, parties of the second part C. D. Fuller, Joseph Cozza, Louis Gasloi; background information for the new agreement.

- The Freeborn County Standard, February 21, 1889.

- Deed, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 241098, June 4, 1907, Grantee C. D. Fuller.

- Advertisement in The Country Home, March, 1908.

- The Freeborn County Standard, July 25, 1888.

- Paula Fiorino.