Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The Gig Harbor Clay Company, Part 2

In our previous column, we began the story of Gig Harbor’s only brickyard. Albert Jonsoni had come from South Africa in 1907 to enter the brick-making business, but it was not going well. In Part 2, we pick up the story in 1908.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

The following is a condensed version of The Gig Harbor Clay Company of Gig Harbor, Copyright 2019 by Greg Spadoni. (The italic numbers in parenthesis are footnotes.)

The Gig Harbor Clay Company, Part 2

Gig Harbor’s local weekly newspaper, The Country Home, reported in March 1908, that Frank Curtis, who owned the old Patrick home in Millville, on Gig Harbor’s west side, was “having two new brick chimneys made from Gig Harbor brick.” (31) (The house no longer exists today.) The newspaper reported in the same issue that another prominent Gig Harbor resident had gone to Vashon Island for the bricks to build his house. “Mr. Andrew Skansie has purchased one of the beautiful waterfront lots of Mrs. Jeresich, opposite Mrs. McGuire’s place, and will erect a fine brick residence. The brick were purchased from a yard at Quartermaster Harbor.”

Andrew Skansie’s house, now a part of Skansie Brothers Park in Gig Harbor, is not faced with Gig Harbor brick. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Why Andrew Skansie didn’t buy his brick in Gig Harbor is not known. The less-than-premium-quality brick he used suggests the Gig Harbor Clay Company’s product was even worse, though there are other possibilities. Jonsoni’s struggling plant may have not been producing enough brick for Skansie’s house at the time, or the Vashon brick may have been cheaper.

Rather than use brick from the Gig Harbor brickyard to build his house in 1908, Andrew Skansie bought these bricks from a yard on Vashon Island. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

That summer, while Jonsoni was working to correct the deficiencies of the brick plant’s production, his wife gave birth to their fifth (and last) child, Gordon. (32)

As the warm season neared its end, the measures taken by the company to improve the quality of its brick were not working. It was becoming clear that much more money needed to be spent, for the processing machinery installed was not capable of handling the type of clay on the site.

Going all in

Although the terms of the property lease with John Novak were very favorable to the brick makers (with the possible exception of the per-brick fee), they either decided on their own or were persuaded by Novak to purchase the land outright. In September of 1908, Joseph Cozzi loaned his three partners $2,600, secured by a mortgage on the brickyard real estate and “all improvements, machinery, fixtures and equipment of every kind” on the premises. (33)

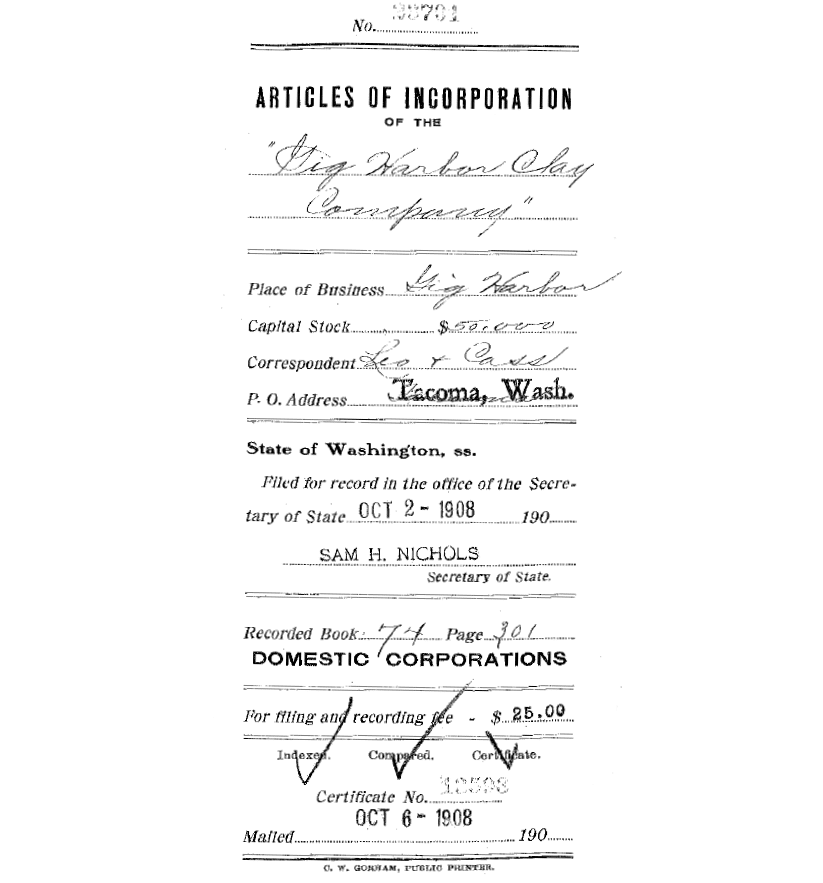

The four partners of the Gig Harbor Brick and Trading Company incorporated the business in October 1908. (34) At the same time the name was changed to the Gig Harbor Clay Company.

The Gig Harbor Clay Company Articles of Incorporation were found in the Washington State Archives in Olympia, WA.

While the other three primary stockholders became trustees of the new corporation, Gasloli did not, having taken a job in Mexico shortly before the incorporation. (35) He remained an owner, however, and Jonsoni signed the incorporation papers on his behalf.

Production troubles continued

Having no practical alternative, in late 1908 the new company bought additional machinery in an attempt to improve the quality of its product. The Clay-Worker, a national trade publication, explained the situation.

“The Gig Harbor Clay Company, of Gig Harbor, a suburb of Tacoma, has been incorporated by C. D. Fuller, J. Cozza, A. J. Jonsoni, and Louis Gasloli, with a capitalization of $50,000. The plant of this company has been erected some time, and, while they have been making brick, the process which they installed has not proven to be a success. The dry press process was not adapted to the blue, hard clay which the plant operates, and the new firm will install a stiff mud machine and a dryer, and hopes to be ready for operation for the next spring trade. They have an excellent opportunity, and will find a ready market in Tacoma for all their brick.” (36)

Seeking outside help

Jonsoni must have finally admitted that his abilities in brick manufacturing were not sufficient to make the business a success, for in the same issue of The Clay-Worker the company was advertising for a knowledgeable superintendent. (37) They wanted the new hire to be confident enough in his abilities as a brick maker to also become an investor.

“SUPERINTENDENT WANTED A brick company on Puget Sound, Wash. wants a competent superintendent. One who is able and willing to back his experience by taking an interest in the business. Here is an excellent opportunity for the right man to establish himself in a good business. Market unlimited, prices good. Do not answer this unless you know your business. Write C. D. Fuller, Gig Harbor, Wash.”

The man they hired, 40-year-old George Beam, (38) was a seasoned clay worker. The News Tribune said that “Mr. Beam comes well recommended as a practical brick maker and has taken charge of the brick business.”

Beam rented the Prentice summer home at the head of the bay and moved his family down from Seattle.

Admitting defeat

The economy, both regional and national, began to show signs of meaningful recovery in the second half of 1908. Albert Jonsoni and his partners had weathered the bad times and were planning on taking advantage of better times ahead as they continued to work on improving the output of the Gig Harbor Clay Company. But some had less patience than others.

In the beginning of 1909, Albert Jonsoni finally threw in the towel on the brick business, either from general frustration or the realization that it was a futile effort. He either sold or gave his stake to Cassius Fuller and Joseph Cozza, sold his house at the north end of the bay, (39) and joined Louis Gasloli in Mexico. (40)

George Beam stayed with the company after Jonsoni left. He bought two lots in the Woodworth Addition to Gig Harbor City in October 1909, (41) apparently expecting to remain in Gig Harbor for a while. If there was not already a house on the property, he built one.

The elusive quality

The Gig Harbor Clay Company’s struggles with quality continued throughout 1909. In April 1909, the Brick and Clay Record reported that “The Gig Harbor Brick Co. made a practical demonstration on their property at Gig Harbor, and proved that the blue clays of the Puget Sound country are not well adapted for the manufacturing of brick by the dry-press process.”

(That is a peculiar statement by the Brick and Clay Record. In 1984, when I excavated for the foundation of the clubhouse of the marina that now occupies the site, I didn’t encounter any blue clay; only gray. In my experience, gray clay is far more common on the Peninsula than blue. Could the gray be considered part of the blue category by the clay industry?)

This brick produced by the Gig Harbor Clay Co. is contaminated with small rocks and sand. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The same brick is not very square. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Having proved their dry-press process to be a failure, Fuller and Cozza doubled down. The Brick and Clay Record went on to say that the company “will remodel the plant into a stiff-mud yard, and start operations again next spring.”

The lack of success continued into 1910.

A money pit

Fuller and Cozza sank even more money into the struggling project. In May, 1910, The Clay-Worker reported that the company had contracted with the Excelsior Kiln Company for the construction of a new kiln. “The Gig Harbor yard has always had some trouble with burning their dry pressed brick,” the note said. “The management hopes with the assistance of this new kiln to eliminate this trouble and make good brick hereafter.”

George Beam was either not convinced and quit, or he was fired, for he went to work as a foreman at the Far West Clay Company in Clay City in East Pierce County, well before the end of 1910. (42)

The January 1, 1911, issue of the Brick and Clay Record noted that the Gig Harbor Clay Company had not solved its production problems in 1910: “The Gig Harbor Brick Co. [actually the Gig Harbor Clay Co. at that time] is still experimenting without very satisfactory results yet.” (43)

In a short mention of the company in February, The News Tribune said a new kiln (it’s not known if it was an Excelsior kiln) was a success, and that the brickyard was back in production with a full crew. “… the Gig Harbor Clay company has begun operations and is now employing about 30 men. … An experimental kiln was tried recently with excellent results, and enough brick for another kiln are now about completed.” (44)

Cassius Fuller doesn’t appear to have been convinced the quality tide had turned. He sold his interest in the still-struggling business to Joseph Cozza. (45)

The 1908 mortgage on the brickworks was declared satisfied by Joseph Cozza on March 4, 1911. (46) That doesn’t convey if the $2,600 he loaned his partners was fully repaid, or whether he forgave all or a part of it. Either way, the grantors were no longer legally liable for any further service on the debt.

False hope

The April 30, 1911, edition of the Tacoma Daily Ledger printed an upbeat piece, forecasting great success for the Gig Harbor Clay Co.

“To the list of Tacoma industries for whose product there has long been an urgent need, is to be added the Gig Harbor Clay company, manufacturers of facing, pressed and common red brick, with an output of 25,000 brick daily, which will hereafter be handled through a Tacoma firm.

“While there are several brick yards in the Northwest and one large one in Tacoma, the Tacoma plant turns out red brick only and none of the other plants produce facing and pressed brick in any considerable quantities. The result has been that the greater part of the pressed and facing brick used in Tacoma has been shipped from the East, against a heavy freight rate and consequent high cost to the consumer.

“During the past week an agreement has been made whereby a firm of dealers in building materials will handle the output of the Gig Harbor yards and the latter will be enlarged and their capacity increased by the addition of new derricks, wharves and kilns, etc., at a cost of $5,000.”

The optimistic outlook seems to have been completely misplaced. The brick yard doesn’t appear to have been operating through most of that summer, if at all. The last newspaper mention found of the Gig Harbor Clay Company is from The News Tribune on August 12. It simply said, “The Gig Harbor brick yard is soon to start making brick again. This will give many employment.” (47)

Harsh reality

The Gig Harbor Clay Company’s long, hard, profitless struggle never turned around. In spite of Albert Jonsoni’s early efforts, and Joseph Cozza’s later attempts, the brick factory in Gig Harbor was a failure. The company was never able to consistently make a product good enough to compete with the other brickyards in the Puget Sound area, or match the quality of facing and pressed brick from out-of-state yards.

The last year of its operation appears to have been 1911, sometime after the rose-colored article in the Tacoma Daily Ledger made the future of Gig Harbor clay products sound bright. That is, if it operated at all that year.

Fini

In 1914 the Gig Harbor Clay Company made the Washington state “List of Companies Stricken From Record Since Last Report Sept. 30, 1912, For Failure To Pay Annual License Fee.” (48)

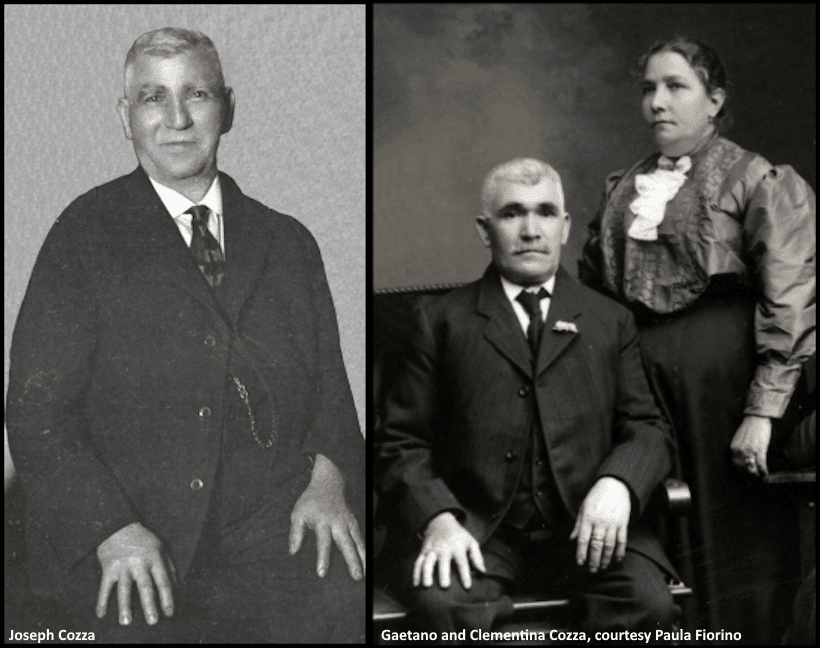

Fractured relationship

After the company’s failure, Joseph Cozza’s very successful poultry store in Tacoma continued to prosper, but his personal life was permanently damaged. His brother Gaetano was so upset over losing his investment in the brickyard that he refused to speak to Joe for the next 16 years. He relented in 1926, only when he learned Joseph was dying.

In 2018, Joe’s great-granddaughter Paula Fiorino recalled what she had been told about Gaetano’s reaction to the news of Joseph’s impending death:

“Gaetano heard about it and came to see him to apologize and say goodbye. My great aunt Lana [Elina Cozza Strommer] told me the story many times and she claims that Gaetano invested in the brickyard, and when it failed his wife Clementina forced an alienation between the two brothers, who lived a few blocks from each other. It was awful, I guess. When Gaetano came to his deathbed, the men were both crying and sobbing and Gaetano kept saying, ‘perdonami, ero così sciocco, perdonami (forgive me, I was such a fool, forgive me)’ and he was hugging Joe as he lay there. I guess it was very touching and the whole family was sobbing.”

The reunion was short-lived, as Joe died the following day.

Joseph Cozza, left, in 1925, and his brother, Gaetano, didn’t speak for 16 years after the Gig Harbor Clay Company went bust. Photos provided by Paula Fiorino.

After the bricks

When the plant closed, the equipment was likely sold to (only slightly) offset the tremendous financial losses of the investors. The buildings, however, remained. Ownership of the abandoned structures reverted to John Novak when he re-acquired the property. What happened on the site — if anything — during the rest of the 1910s has been lost to history.

The Bay-Island News recorded what was planned there for 1920. (49)

“Gig Harbor is to have a fruit cannery. It is to be made ready for the present season’s crop. Novak Brothers are the men who are providing us with this much-needed improvement. The site is that of the old brickyard adjoining the C. O. Austin sawmill. The old buildings are now being torn down and ground cleared for the new structure … The site is ideal for the purpose, there being an abundance of spring water available — a most necessary and valuable feature — while the bay will take care of all the waste water, fruits, etc. … For several years there have been efforts to induce outside parties to come in and establish a cannery; this failing, home talent comes to the rescue and supplies the thing needed.”

The newspaper followed up the next month with a progress report. (50)

“Work is progressing steadily on the cannery building erected by the Novak Brothers … The boys are putting up a good building and have one of the finest sites possible for such an industry. They also have an abundance of pure spring water for their purpose, and all refuse can easily be dumped into the bay at the back of the building.”

The “much-needed improvement” was never realized. Gig Harbor never did get a fruit cannery. A building was constructed, partly on land and partly over the water, but sat unused.

(That may have been for the better. The mess such a business would’ve dumped into the harbor would likely not have been tolerated by other waterfront property owners for very long.)

A new use for an empty building

In early 1921 the Bay-Island News revealed that “The building which the Novak boys put up last year with the intention of establishing a canning factory is being re-floored and placed in condition to roller skating and dance purposes.” (51)

Known variously as the Silvery Glide Hall, the Silver Glide Hall, and Novak’s Hall, it was a local fixture for the next 12 years. It hosted dances, parties and political, church, and club meetings, but no roller skating was ever documented. The last known function in the hall, sponsored by the Crescent Valley P.T.A., was a “Hard Times” dance on the third Saturday in January 1933, (52) during the Great Depression.

The hall was torn down later in 1933 and some of the salvaged lumber was used to build the Gilich netshed about a thousand feet to the east-southeast, by John Novak’s son-in-law, Tony Gilich. It’s still in use today, as the Blair netshed.

The Blair netshed, made from lumber salvaged from the old Silvery Glide Hall, will continue to be in use for many more years, for just five days before this story was posted, it was in the process of getting a new roof. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The barren brickyard site then became a log dump, used by a variety of local loggers into the 1950s and possibly the early 1960s. An occasional building was barged in to the harbor and offloaded there for transport elsewhere.

The site was sometimes used for the importation and storage of other things, even when the Silvery Glide was in operation. In 1925 Tacoma City Light rented the area beside the hall from John Novak during the construction of the Cushman power lines for “a storage ground for supplies for the Cushman project in [the] form of wire cable, lumber, etc. These supplies will be transported by auto truck.” (53)

Next time

On Feb. 9, Part 3 of The Gig Harbor Clay Company follows the Jonsolis and Gaslolis after they’d moved on to other things. It also ties a local family to the current use of the old brickyard site.

Greg Spadoni, Jan. 26, 2026

Footnotes

- The Country Home, March 7(?), 1908, page 11, column 3.

- The News Tribune, August 29, 1908, page 13, and the Tacoma Daily Ledger, August 30, 1908, page 28, under Gig Harbor news, “Born—Wednesday, August 24, to Mr. and Mrs. Jonsoin [sic], a boy.”

Find A Grave Memorial ID: 228081043. - Mortgage dated September 22, 1908, recorded at the Pierce County Auditor’s Office on September 30, 1908, Fee No. 275592, Book 164 of Mortgages, page 337. Parties of the first part, C. D. Fuller and Nellie Osborn, his wife; Albert Jonsoni and Rose Annie Jonsoni, his wife; Louis Gasloli and Martina Gasloli, his wife, to the party of the second part, Joseph Cozza.

No deed or contract for the actual sale was found. - Gig Harbor Clay Company Articles of Incorporation, October 6, 1908, accessed at the Washington State Archives in Olympia, WA.

- The Tacoma Daily Ledger, October 11, 1908, page 28, Gig Harbor News, “Mr. Gasloli left for Old Mexico last week, where he will spend the winter.”

- The Clay-Worker, Volumes 49-50, page 377, “Puget Sound Clay Notes.”

- The Clay-Worker, Volumes 49-50, page 312.

- 38. The News Tribune, August 15, 1908, page 13.

- Deed, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 285165, dated February 8, 1909, recorded February 9, 1909, Grantor Albert Jonsoni and Rose Anna Jonsoni.

- The News Tribune, February 20, 1909, “Mr. Johnson [sic] has sold his little home at the head of the bay … and will move his family to Mexico at once.”

- Deed, Pierce County Auditor’s Fee No. 301669, dated October 4, 1909, recorded October 18, 1909, Grantee Mrs. Mary Beam (George Beam’s wife).

- The Tacoma Daily Ledger, September 11, 1910, page 38

- Page 91

- The News Tribune, February 14, 1911, page 2.

- The News Tribune, February 17, 1911, page 11.

- Face Satisfaction of Mortgage, dated March 6, 1911, recorded March 6, 1911, Fee No. 335083, Book 164 of Mortgages, page 337. (“Face” meaning that the notice of satisfaction was printed across the face of the original mortgage record.)

The description of the property mortgaged might be in error. - The News Tribune, August 12, 1911, page 8. The same two sentences appeared in the August 13, 1911 Tacoma Daily Ledger, page 30.

- State of Washington Thirteenth Biennial Report of the Secretary of State, October 1, 1912, September 30, 1914, I. M. Howell, Secretary of State, page 66.

- Bay-Island News, March 12, 1920, page 1, column 5, “Cannery For Gig Harbor.”

- Bay-Island News, April 16, 1920, page 1, column 5, “Cannery Building.”

- Bay-Island News, March 25, 1921, page 6, column 2.

- An advertising bill for the dance in the collection of The Washington State Historical Society, Catalog ID: 1998.1.18.

- The Peninsula Gateway, July 3, 1925, page 8, column 2.