Community Education

Holocaust survivor shares harrowing story with Kopachuck Middle School students

Students at Kopachuck Middle School listened with rapt attention to the guest speaker at Tuesday’s assembly. They gave him rousing applause afterward, with whistles and cheers. Some approached the podium to shake his hand and get his autograph.

This was no pop star, sports hero or Internet influencer, however. Pete Metzelaar, 90, came to tell the students about his youth hiding and fleeing from soldiers of the Nazi regime during World War II.

Metzelaar, who is Jewish, was there to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day on behalf of the Holocaust Center for Humanity of Seattle. Eighth graders at the school will study the Holocaust this year as part of their English Language Arts curriculum. The entire student body, grades six through eight, heard his speech.

Pete Metzelaar discusses his experience during the Holocaust with Kopachuck Middle School students on Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2026. Photo by Vince Dice

Metzelaar has been sharing his story with students and other groups since 1993. Each time, he relives the details of those harrowing years.

“Everything that I’m telling you now, there is no Hollywood,” he said. “There’s no playing in there. Everything in fact happened. If I remember it, it is part of the historical documentation of these things that happened.”

Nazis occupy Netherlands

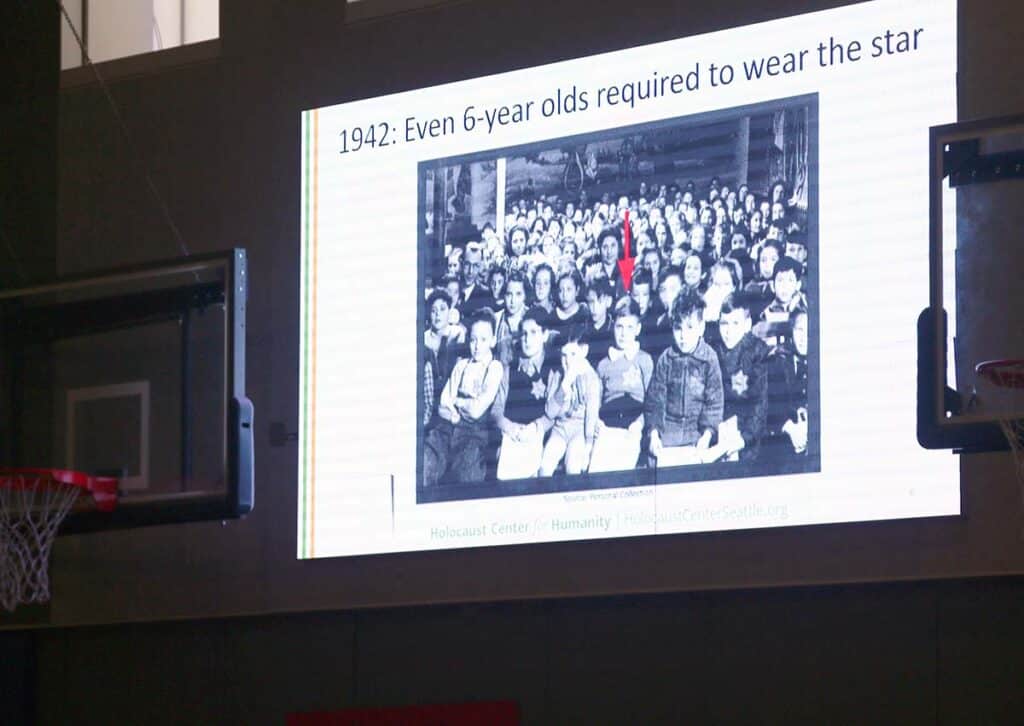

Metzelaar was born an only child in 1935 in Amsterdam, Netherlands. He was 6 or 7 years old when the Nazis increased pressure on Dutch Jews in the country, which had been occupied by Adolf Hitler’s regime since 1940.

People of the Jewish faith were forced to abide by Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws, a lengthy list of rules meant to strip Jews of their human rights. They had to abide by curfews, couldn’t attend movie theaters and were banned from public transit, as examples. They weren’t even allowed to own radios, bicycles or boats.

Metzelaar showed a photo of his mother wearing the humiliating yellow star with the word “Jew” that the Nazis required. Failing to wear the star would do no good, as the Nazis kept track of Jews’ identification through hospital records. They’d stop you on the street for no reason and ask for ID, Metzelaar said.

The Nazis began rounding up Jews and taking them away for “relocation.” No one knew where. Everyone asked “why?”

“It turned out that more and more people started to disappear,” Metzelaar said. “Somebody’s aunt, somebody’s dad, somebody’s grandmother didn’t show up home that night. Where did they go?”

Pete Metzelaar discusses his experience during the Holocaust with Kopachuck Middle School students on Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2026. Photo by Vince Dice

Family members arrested

In 1942, Metzelaar’s own family was caught up in the relocation. His uncle, then his grandparents were arrested. As a 7-year-old boy, he didn’t understand any of this, but he knew it had something to do with the German soldiers out in the street.

His father, who owned a small rowboat and loved to fish, was arrested in June 1942. “And that was the last we ever saw of him. We had no idea where he went,” Metzelaar said.

Later, after he moved to the United States following the war, Metzelaar found a document showing that his father, grandparents and uncle had died at a concentration camp. Nazis killed 6 million Jews during their occupation of Europe, many exterminated in gas chambers or killed by disease or starvation in camps such as the notorious Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in occupied Poland.

His mother, now fully alarmed for their safety, sought help from the Dutch Underground, a network that aided Jews at great risk to themselves and their families.

“These people, if they ever got caught by a German, helping a Jew, it would be a bullet in the head on the spot,” Metzelaar said.

Hiding under floorboards

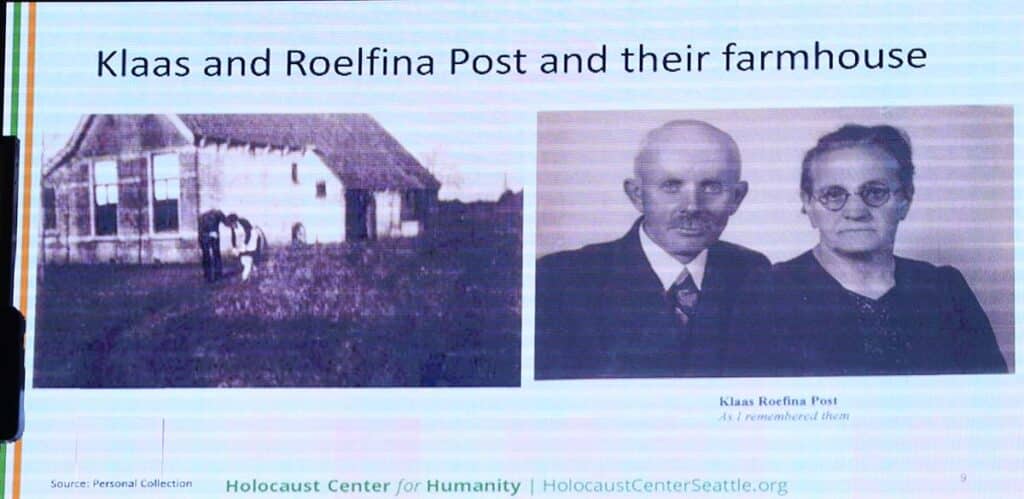

A couple with a farm in the northern Netherlands took in Metzelaar and his mother. Klaas and Roefina Post worked hard from sunup to sundown and readily shared what they grew with the refugees.

“They became like surrogate parents to me,” Metzelaar said. “They were such decent, compassionate people. Not only did they take us in, they risked their lives and their entire family’s life by doing it.”

Soon the Nazi raids broadened to the countryside. Klaas knew it was just a matter of time before trucks full of soldiers came rumbling down their lane. He sawed up a section of pine floorboards to create a coffin-like chamber underneath. When the Nazis would come, Metzelaar and his mother would crawl into the chamber and lie side by side. Klass would put the boards back, and Roefina would toss a rug on top.

“Mom and I would lay in the dirt, petrified, soldiers walking a foot over our heads,” Metzelaar recounted. “All it would have taken was one cough, one sneeze, one hiccup, and it would have been over.”

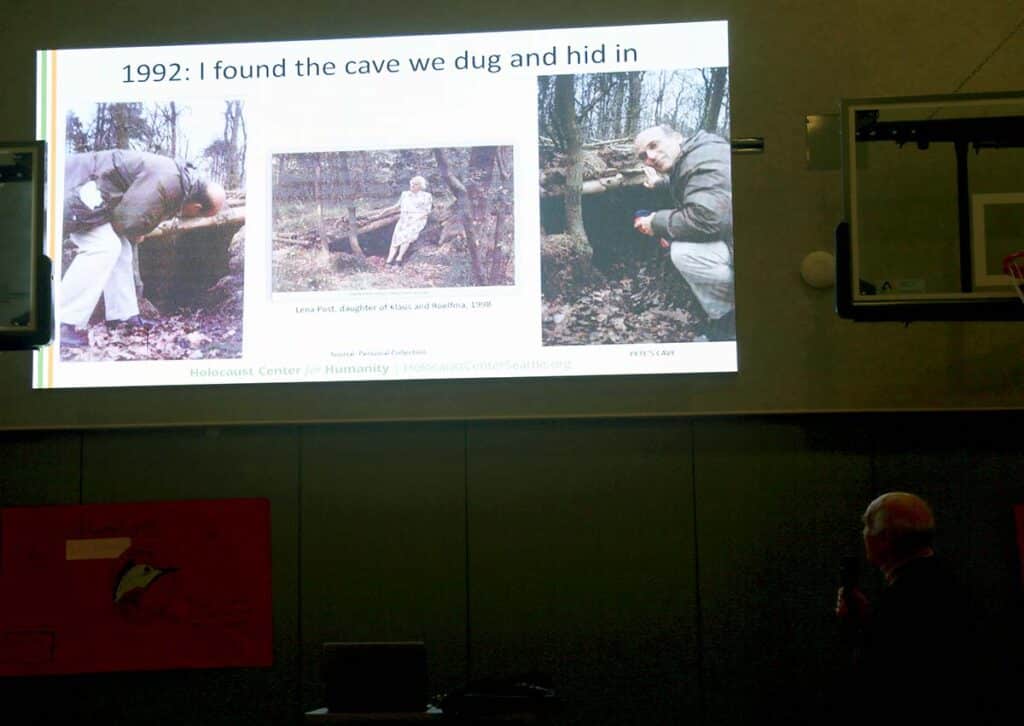

As the raids became more frequent, Klaas decided a better hiding place was needed. He and young Metzelaar dug a “cave” in the woods about 200 yards from the house. Klaas covered it with branches and made a stick-lattice door.

“There was just enough room for Mom and I, body to body, to lay in there,” Metzelaar said.

Whenever the dirt trickled down on them, he was terrified of being buried alive. But the cave held, and it saved them from discovery on multiple occasions.

Allied air raids begin

Metzelaar and his mother spent more than two years on the Posts’ farm. In all that time, the refugees never went out in the daylight, lest neighbors not bent on saving the Jews see them and turn them in. Klaas made homemade toys for the boy, but Metzelaar felt isolated, invisible, erased.

Forced into hiding, he said, “We don’t exist. We don’t have a body, we don’t have a soul. We don’t have anything, because that could be the last day on this planet.”

During the latter part of their stay, the Allies began bombing runs out of Britain to destroy the German war machine.

Metzelaar remembers his terror the first time a squadron of B-17 Bombers flew at night over the farm, which was in their flight path. The windows rattled and vapor trails covered the sky.

“They came over by the thousands,” he said. “The noise of those bombers flying overhead was just deafening.”

Images from the presentation show Klaas and Roefina Post and the farmhouse in which they sheltered Peter Metzelaar and his mother. Photo by Vince Dice

The Nazis’ raids became yet more frequent. Metzelaar’s mother decided staying on the farm was too dangerous for everyone. Again, through the Underground, she found two women in The Hague willing to let them stay in their apartment building.

“I remember so much about Klaas and Roefina, their decency, their humanity, their courage,” Metzler said. “These women … they weren’t very nice.”

Pete goes to school

The Germans instituted strict rationing. Metzelaar’s new hosts, unlike the Posts, were stingy with their probably meager supplies.

“They wouldn’t share their food. We had scraps from their table. I was hungry all the time,” he said.

Twice, his mother broke curfew and took an enormous risk, sneaking out at night for a loaf of bread.

Somehow, she got a fake ID for young Pete and enrolled him in the local public school under the last name of “Pelt,” He was terrified at first. But without his yellow star, he blended in.

“They didn’t know who I was. I was just one of the guys,” he said.

Eventually, the women got scared. Metzelaar’s mother learned that they planned to turn them in. Again, through the Underground, she found a safe apartment back in their hometown of Amsterdam. Getting there, however, would be a problem as the only highway was closed to the public, for use only by Nazi troops.

Mother’s escape plan

It was then that Metzelaar’s mother hatched the boldest — some might say craziest — plan ever.

One night, Metzelaar found his mother sewing some bedsheets. What was she doing? She told him to go back to sleep. Out of those bedsheets she made a skirt, a top and a head covering.

They left the apartment in the middle of a cold winter night with nothing but the clothes on their backs, in his mother’s case, the outfit she had made. Metzelaar still had no clue about her plan.

“She wrapped that contraption around herself and we tippy toed out of the apartment,” he said.

A slide shows Peter Metzelaar as a child, wearing a Star of David patch. Photo by Vince Dice

Hitchhiking with the Nazis

Now nearly 10 years old, Metzelaar figured out they were heading to the highway, and he was “petrified.” When he protested, his mother told him to be quiet and follow her. They trudged several miles through the snow until Metzelaar could hear the soldiers and see the trucks and tanks rumbling by.

“We came to the highway, I’m hanging onto my mom for dear life. And now, my mom does something that, as the expression goes, the doo doo was going to hit the fan,” Metzelaar said, his voice rising. “As she’s standing by the highway, she started to hitchhike. I said, ‘What are you doing? … These people want to kill us!”

No Plan B

Before long, a flatbed truck pulled to a stop. A Nazi officer jumped out and read his mom the riot act. Miraculously though, he gave her the chance to explain why they were there.

Metzelaar’s mom told the officer she was escorting the boy to safety since his parents had been killed in a British bombing raid.

“As you can see, I’m a nurse with the International Red Cross. I’m taking him to an orphanage in Amsterdam,” she said.

Metzelaar was “scared out of my gourd,” as the Nazi officer walked his mother over to the cab and helped her up beside the driver. Then, without a word, he lifted Metzelaar up into the snow-filled back of the truck.

“My mom is sitting between the two Nazi officers, and I’m sitting in the snow by myself,” Metzelaar said. “Are you ready for this? They took us to Amsterdam. She fooled ’em! She fooled ’em! … How did she ever come up with a plan like that? To hitchhike with the people who wanted to kill us!”

Life after the war

In May 1945, Allied forces liberated the Netherlands.

In 1949, Metzelaar and his mother moved to the United States. He became a citizen, served in the U.S. Army and had a career as a radiology technologist.

Metzelaar has made several trips to Europe to visit sites of the war, including Klaas and Roefina’s farm, which he and his family found through inquiries at a bank in the town nearby. They also found the “cave” in the forest, which was still intact, untouched over decades.

“The strangest feeling, it was like I was 7, 8 years old again,” he said.

Klaas and Roefina had been dead about a decade by the time he made his pilgrimage. Metzelaar bitterly regrets that he didn’t make the trip sooner.

He now lives in Seattle with his wife, Bea. His mother, who lived in Los Angeles, died in 1994 at age 89.

Peter Metzelaar gestures at a projector screen while discussing his experience during the Holocaust with students at Kopachuck Middle School on Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2026. Photo by Vince Dice

Message to students

Metzelaar said he shared his story as a cautionary tale for the students, warning them against the power of propaganda, “misleading information to promote a particular cause or view.”

Everyone is entitled to their opinion, he said, but don’t let opinion stand as fact. Learn the history and look for documentation of events. He said he hopes to promote tolerance and independent thinking. He ended with this:

“So, guys, stick with your studies. You might not think that you have anything to do with it, but absolutely, right now in the world, there are things that are happening that happened when Hitler came to power, and you’ve just got to be aware of it.”

He left them with one last message: “Go, Seahawks!”

Peter Metzelaar explains how he found the cave in which he and his mother hid from Nazi soldiers, 50 years later. Photo by Vince Dice

What students said

Hannah Siegert, in eighth grade, said she found Metzelaar’s talk “emotional.”

“It was nice to hear from someone who was actually there and experienced it,” said Laila Gilchrist, also in eighth grade.

She was interested to learn how many people helped the Jews.

Both students had a chance to hear Metzelaar speak before, as he was invited back to Kopachuck for an encore this year. But it was sixth grader Ellie Stephens’ first time hearing about the Holocaust.

“I believe it was very inspiring but also a little heartbreaking because of how he had to hide and being scared all the time,” she said.

Stephens was sad to hear how Metzelaar lost most of his family. She was uplifted to hear that, although he never saw Klaas and Roefina again, he connected with their daughter and extended family decades after the war. “It kind of brought him a little joy,” she said.

Peter Metzelaar, a Holocaust survivor, speaks to students at Kopachuck Middle School on Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2026. Photo by Vince Dice