Arts & Entertainment Community

BoatShop digitizing a photographic ‘treasure trove of history’

Leaders of the non-profit Gig Harbor BoatShop are dealing with a lot of negatives.

A whole lot.

Some 10,000 or so, they say — photographic negatives on glass, 4×5 flat film, 35mm roll film, slides and even a few movie films.

“It’s an incredible treasure trove of history, showcasing the Golden Age of yachting,” enthuses Jan Hein, a BoatShop volunteer. Hein is among those spearheading a project to digitize the collection

Prolific photographer

The negatives, mostly maritime scenes, are a mere fraction of the life’s work of a prolific 20th century Northwest professional photographer you may never have heard of. However, if you’ve been in Gig Harbor for a while, you are likely to have seen one or more of his photographs, often displayed as art in local museums, publications, clubs and homes.

If nothing else, you may have at least encountered a famous panorama of 30 or more fishing boats lined up in the harbor for a Blessing of the Fleet ceremony in the early 1970s.

A photo mural created from Ollar images of the 1971 Blessing of the Fleet.

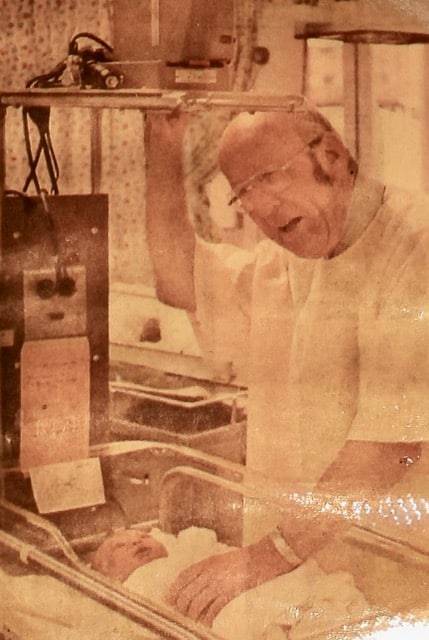

Beyond that, if you were born at Tacoma General Hospital between the 1940s and mid-1970s, there’s beyond a fair chance that he took the first picture of baby you.

When retiring in 1977 as staff photographer at the hospital for more than three decades, he estimated to an interviewer that he had taken 80,000 pictures of newborns, “give or take a few.”

And beyond that, if you were aboard most any kind of boat in the harbor, on Puget Sound, or on other local waters during the heart of the 20th century, he may have taken pictures of that too, possibly while out and about on his own wooden cabin cruiser “Shutter Bug.”

Or, as a small plane pilot, he might have been overhead, taking iconic aerial photo of boats and our region’s seascapes and landscapes.

Kenny Ollar

The photographer: Kenneth Griffin Ollar, or “Kenny,” as those who remember him tend to call him.

One of those who remembers Kenny is Guy Hoppen, executive director of the Gig Harbor BoatShop. Hoppen is the son of Ed Hoppen, former co-owner of the Eddon Boatyard, and present owner of the Ollar maritime negatives.

“I knew him all my life,” Hoppen told Gig Harbor Now.

“When I was a kid, I used to see him around my dad’s boatyard,” he recalls. Later in both their lives, they became closer and Ollar, a few years before his death in 2007, transferred ownership of the mostly maritime-related negatives to Hoppen.

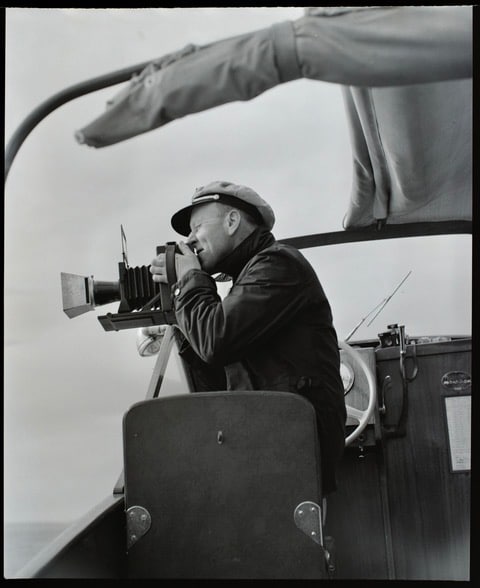

Kenny Ollar. Photo credit: Zebeck, GHB Photo Archive

Hoppen, a photographer himself, says both he and Ollar wanted to see the negatives kept together as a collection.

Presently, they are in the custody of the BoatShop nonprofit while its board and Hoppen work out a lease or other agreements intended to provide both long-term public access to them and to allow their use to help support the organization.

While those details develop, the task of digitizing so many images has begun in a neat and clean makeshift studio in city-owned Eddon Boat Park.

A daunting task

In the years since acquiring the negatives, Hoppen has done some organizing, sorting and printing of Ollar’s work. Recently, the BoatShop acquired digitizing gear and hired a part-time employee to speed processing of the collection.

The worker, Monica Veles, who was raised in — and lives in — Gig Harbor, formerly served as a staff volunteer at the BoatShop.

“I didn’t grow up boating,” the 29-year-old told Gig Harbor Now, but says she learned much of what she now knows of it through her association with the BoatShop.

Loving photography, she honed her skills with training through a University of Washington program, helping lay a foundation for her own local business. She specializes in portrait, family group and special occasion pictures, most taken — like Ollar’s work — in natural light and outdoor settings.

On her “first solo day on the job,” she told a Gig Harbor Now reporter why she’s looking forward to doing the daunting task now arrayed on shelves and files laden with cardboard boxes, files, and stacks of negatives.

“It’s really important to document these photos,” she said, adding moments later, “and to share this history.”

Monica Veles examines a Kenny Ollar negative at the Gig Harbor BoatShop. Photo by Chapin Day

A particular set of skills

A BoatShop board member who carries impeccable mentor credentials trained Veles to do the work.

Professor Emeritus Richard Gray, 70, is an internationally known and exhibited photographer who has lived in Gig Harbor since 2021. He served almost 40 years on the faculty at Notre Dame, including nine as chairman the Indiana university’s Department of Art, Art History, and Design.

His resume also includes “former Chair of the National Board of Directors for the Society for Photographic Education.”

A quote from his Notre Dame departmental biography: “The majority of his creative career at Notre Dame focused on exploring photography’s representation of human identity and the dialectic relationship between the visible and sub-visible aspects of our lives. His work utilizing microscopes to photograph human cells or thermal cameras to record the phenomenon of body heat repositioned these trusted conveyors of information as complex provocateurs of what it means to be photographed.”

(Reporter’s note: Whew! Seems qualified.)

He also qualifies as a mariner. The Grays have a 38-foot Ocean Alexander motor yacht moored in Gig Harbor.

A Kenny Ollar photo of a ferry, with Mount Rainier in the background.

Time-consuming process

As Gray tells it, a year or so after he and his wife moved to Gig Harbor he went to the Boatshop, hoping to crew on one of its prize attractions, the fishing vessel “Veteran.”

Meeting and chatting with Hoppen, Gray mentioned his photography art and education career and his interest in digital gear.

Suddenly, the focus of the conversation changed as Hoppen said something along the lines of “Hmmm. I’ve got something I’d like to show you” and led him to the stash of negatives.

“I fell right into that trap,” Gray chuckled while speaking last week to Gig Harbor Now.

In the next two years after that fateful chat, the digitization plan developed and slowly took shape. Then, Gray says, “About a year ago, we put the hammer down,” accelerating progress within a small but committed team. To date, Gray estimates that only 8 to 10% of the negatives have been processed.

Gray, Hoppen, new employee Veles, and board member Hein presently are among the very few people trained — and possessing the needed skillset and patience — to artfully perform the careful, time-consuming steps in processing the fragile, aging negatives.

Gig Harbor BoatShop board member Jan Hein and volunteer Richard Gray. Photo by Chapin Day

Film deteriorating

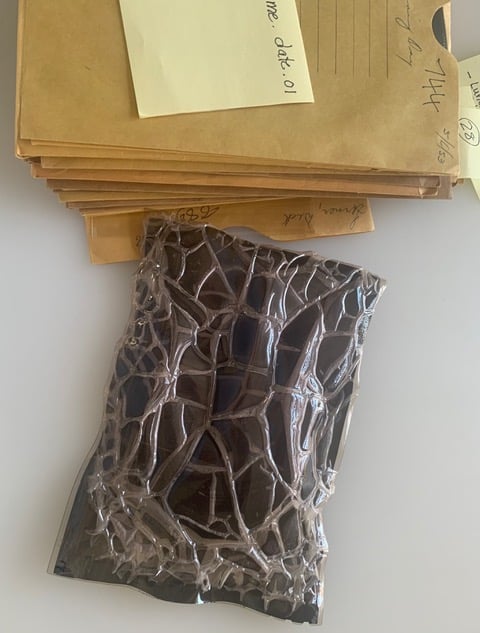

Time and storage have already damaged some of them, causing flaws or, in a few cases, turning flat film into cracked, swollen, and unreadable trash.

Such deterioration creates “some urgency,” Hoppen noted, to get the digitization project done.

Negatives are deteriorating, lending urgency to the BoatShop’s project.

Recently, team members have been discussing among themselves and others involved in the project whether the time is right to seek interested volunteers.

Among even the best-intended volunteers, Gray says, “Not everyone is suitable for the task. This is serious business.”

While Hoppen shares some of those concerns, he does encourage anyone who happens to have Ollar negatives or prints to at least allow the Boatshop team to make digital copies of images not already in the collection.

A few completed and mounted Ollar photos from the negative collection.

In addition, Hoppen’s not at all hesitant about seeking another resource to complete the project.

Money.

He credits generous support from Sutter-family owned “Fisheries Supply,” a 96-year-old Seattle-based chandlery, for helping seed the digitization. He harbors hopes more donors will step forward as they learn of the project and of Ollar’s work, which he likens in some respects to the photographs of Northwest photography giants like Edward and Asahel Curtis.

As they were, Hoppen says, “Kenny was very passionate about his photography.”

Kenny Ollar’s journey to photography

In a biographical interview Hoppen recorded with Ollar a few years before his death in 2007, Ollar recalled a 1950s yacht club magazine article. Its author compared him to one of classic yachting’s pioneer and premier photographers, Morris “Rosy” Rosenfeld, a noted East Coast chronicler of the dramatic and graceful J-Boats and later America’s Cup sail racing yachts throughout the first half of the 20th century.

“We consider him as the Rosenfeld of the Northwest,” as Ollar remembered the writer’s words.

“That was the biggest compliment I think I have ever had paid me. Yeah. Rosenfeld of the Northwest.”

In addition to offering selected Ollar photo prints at its annual fundraising events, the BoatShop sells quality framed prints of some of Ollar’s photos in its retail shop. A black-and-white Ollar aerial of Day Island on a store display wall recently bore a $425 price tag.

A Kenny Ollar photo for sale at the Gig Harbor BoatShop. Photo by Chapin Day

Funds from the nonprofit’s store sales help finance BoatShop community programs. Project leaders envision other fundraising opportunities, online and off, when the digitization is complete.

Ollar, who grew up in Tacoma, would understand the effort needed to turn his photographic work into income.

In his recorded interview with Hoppen, Ollan recalled, “Shortly after birth I was having pictures taken of me with a camera in my hand,” likely snapped by his father, who he described as “a very fine amateur photographer.

“As I started to walk, well Dad kept showing me how to use a tripod and all the good things about what not to do. I guess it just came natural.”

‘A sissy hobby’

However, he said, he didn’t put those lessons to work during his childhood because he regarded photography as “a sissy hobby.” His interest revved up in his teen and college years and, at age 19 in Depression-wracked 1931, he began to freelance, shooting pictures for pay.

Among those whose could pay in those financially perilous times were boat builders, not to mention the people who bought those sail, power, and commercial vessels.

“As time went on,” he told Hoppen, “I built a little business by hearsay, by word of mouth, did newspaper work.”

Kenny Ollar with an infant in 1977. The Tacoma News Tribune newspaper ran a story about his retirement.

In 1940, he turned a part-time, low-pay job at Tacoma General into full-time. It also led to his marriage to his wife Kathryn, a nurse he met in the new-born nursery while taking some of the first of those “80,000 … give or take a few” baby pictures.

In 1942, his Army service during World War II interrupted the couple’s time together and his job. Ollar spent much of his Army stint in photography and signal corps units under General George S. Patton.

With the end of the war in 1945, he came back home and went right back to work at Tacoma General as its staff photographer, a job entailing an assignment range from nurse graduations, to publicity shots, to detailed medical procedures, to autopsies, and, of course, the babies.

A measurable legacy

In his free time, along with raising a family, he continued to freelance and pursue other interests, foremost among them his love of boating, boaters, and boating photography.

The Ollar headstone at Haven of Rest in Gig Harbor.

What Hoppen called Ollar’s passion for his profession is engraved in stone on an Ollar family niche in a columbarium at Gig Harbor’s Haven of Rest cemetery. Next to Kenny’s name: A classic camera mounted on a tripod.

That “sissy hobby” had become a fitting memorial to a 94-year life and an inspiration to those now trying to ensure that his legacy of negatives yields a positive result for the historical record and the worlds and people he loved.

Kenny Ollar and others aboard the Shutter Bug.