Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | A history mystery at the Donkey Creek Bridge

In addition to being a history mystery, today’s subject is also a traffic mystery. But history mystery sounds better, so that’s the title. History traffic mystery is more to the point, but sounds worse. Specifically, it’s a traffic accidents history mystery, but that’s even worser.

Speaking of accidents, the choice of the last word in the previous paragraph is not one. It’s a serious experiment to see if the editor lets me get away with using worser … OK, a semi-serious experiment. If I was truly serious, I’d simply ask him in advance. But I don’t like bothering people with such trivial matters. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say he’s got more important things to do than advise Spadoni on minor fluctuations of the English language.

(Editor’s note: I don’t, really. That’s sort of what my job is.)

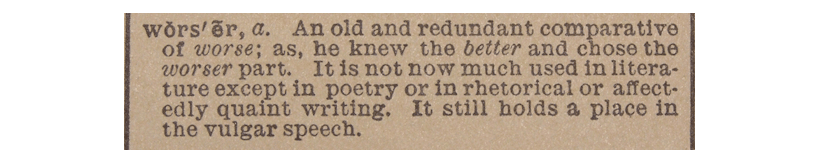

It’s interesting to note, however, that in the time it took me to type that ridiculous explanation, I could’ve come up with a better word than worser. It’s just one of those cases where after investing a certain amount of time in something, even if it’s stupid, you’re reluctant to give it up. Besides, to let it go would almost be an admission of failure, which it isn’t. Worser is actually a real, acceptable word. At least it was, according to the 1942 edition of Webster’s Universities Dictionary, Unabridged.

The definition of “worser” in the 1942 edition of Webster’s Universities Dictionary, Unabridged, page 1985, column 2.

“worser, a. An old and redundant comparative of worse; as, he knew the better and chose the worser part. It is not now much used in literature except in poetry or in rhetorical or affectedly quaint writing. It still holds a place in the vulgar speech.”

Look at how many times it perfectly describes my writing style: old and redundant; affectedly quaint; vulgar speech.

Why, it’s almost as if Daniel Webster himself had been reading my column!

Donkey Creek Bridge

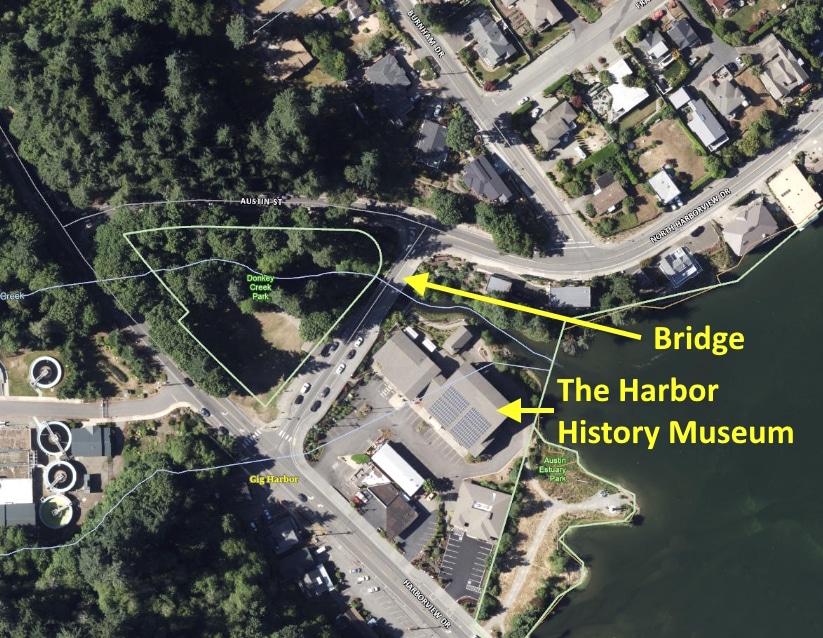

Anyway, today North Harborview Drive crosses a concrete bridge as it passes over Donkey Creek beside the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor. Every car that starts across it makes it to the other side. Nobody drives off the side of it, through the railing. But many people did drive off the side of the previous bridge, through the railing.

The current bridge over Donkey Creek next to the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

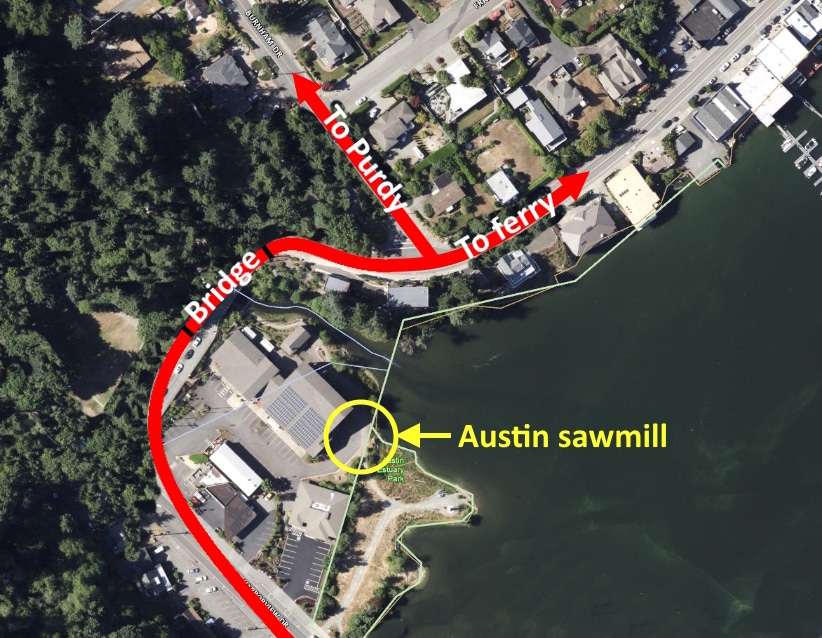

Built in 1920 and removed in 1949, the previous bridge, made of wood, was the most traffic accident-prone site in Gig Harbor for a good number of years. The newspaper descriptions of the crashes very often mentioned a sharp curve involved. Old maps show the curves, but they don’t look particularly sharp. It took me a couple years to find the clue that finally made sense out of all the sharp curve talk. That clue is part of the answer to today’s questions, so won’t be revealed this week.

The following is how I saw the situation before finding the key clue. It’s a clear demonstration of how my ignorance sometimes gets in the way of understanding something.

Nameless creek, nameless bridge

As far as local residents were concerned, Donkey Creek had no official or even unofficial name during the first half of the 20th century. That made referring to the old, wooden bridge problematic. As the location of many automobile accidents over many years, it needed to be identified in news reports. The Bay-Island News, the local weekly newspaper (renamed The Peninsula Gateway after a change of ownership), sometimes referred to it as being near whatever other landmark was closest to it at the time.

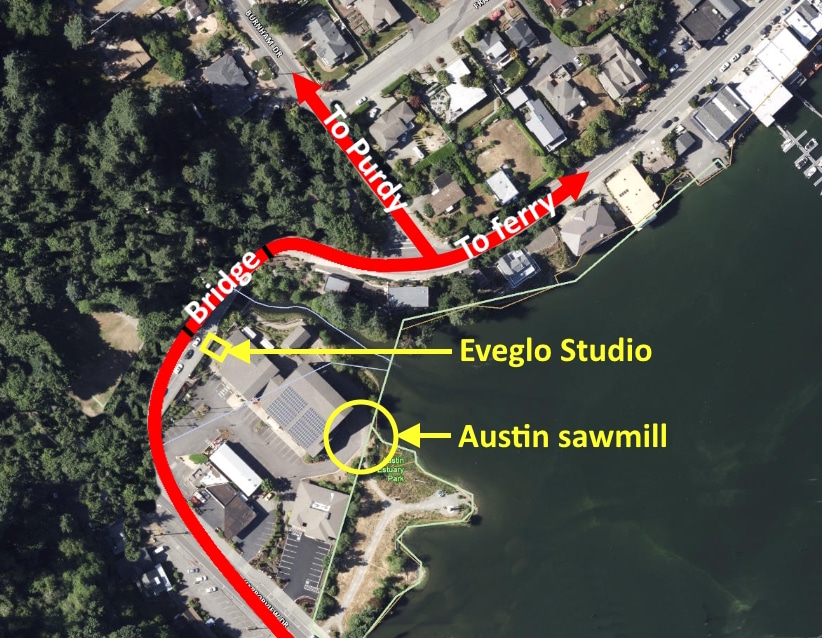

One of the earliest mentions in the newspaper called it “the big bridge near the Austin mill,” because the mill, which was located at the east end of where the Harbor History Museum now stands, was the only other notable feature in the area.

The red line shows the route of the new road and bridge in 1920. The road to Bremerton, through Purdy, began at the bottom of the steep hill on Burnham Drive. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Although it originally had a wood deck, the bridge was part of the first paved road on the Gig Harbor Peninsula. In 1920, when the road from the ferry landing at the north end of the bay to the steamer dock at the foot of Soundview Drive was being prepared for a concrete surface, the bridge was built to replace the original span. The first wooden bridge was built for wagons and horses. The new bridge was constructed for automobiles. Pedestrians crossed it at their own peril. Inattentive or out-of-control drivers were a real danger to people crossing the bridge on foot.

A good example of a car out of control on the bridge involved a local man, Pete Skarponi. On Feb. 2, 1923, the Bay-Island News said that “Pete Skarponi had a narrow escape last Sunday afternoon when his car skidded on the bridge at Austin’s sawmill and came near going over into the bay. A broken bumper, a front wheel torn off, a badly bent fender, and a good scare to the occupants of the car was the result.”

Taking note of the rising number of accidents and near-accidents on the still almost-new wooden span, The Peninsula Gateway ran an editorial in its March 20, 1925, edition.

“It has been noted by many pedestrians that at time ones [sic] life is in danger while crossing on foot, the big bridge near the Austin mill. This is because of reckless auto drivers. It is not uncommon for pedestrians to be forced to climb upon the railings of the bridge to escape being knocked down. With the advent of the heavy spring and summer traffic conditions will be much worse and it will be a wonder if some one is not killed at this bridge. A solution of this problem would be a narrow walk along one side of the bridge for the accommodation of pedestrians.

We believe that the county should by all means, put a walk in at this place.”

Although the U.S. was well into the automobile age by the time that editorial was published, walking was still a very common means of transportation. Many people did not have a car in the 1920s. With no sidewalks anywhere in Gig Harbor except for boardwalks in front of a few commercial buildings, being a pedestrian on public roads could be a risky endeavor, especially on a bridge where there was nowhere to retreat to avoid a recklessly driven car.

A new location reference

In 1926 a new building, the Eveglo Studio, was put up right next to the bridge, where the west end of the museum now stands. Since it was much closer to the bridge than the sawmill, it became a new reference point in describing the location of the accident-plagued bridge. On June 4, 1926, The Peninsula Gateway reported a head-on collision “on the bridge by the new Hunt music store.”

The Eveglo Studio, built right next to the bridge, gave its location in its early advertising as “At The Bridge.” Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

For no discernible reason, at random times the newspaper wouldn’t use any reference to the bridge’s location, calling it simply “the Gig Harbor bridge,” as it did later in 1926. This, in spite of the fact that there was more than one bridge in Gig Harbor at the time.

In September, 1927, the Federated Clubs of the Peninsula proposed to pay for lighting the “Gig Harbor and Purdy bridges.” No mention was made of the Austin sawmill or the Hunt music store.

The Peninsula Gateway was again calling it “the Austin bridge” in 1930, even though the Hunt music store building was still closer to it than the mill. “The matter of straightening the state highway at the Austin bridge was turned over to a committee composed of Lee Makovitch, N. C. Neilson and Mitchell Skansie.”

That’s an indirect reference to one or more sharp curves approaching the bridge.

At the beginning of 1932, the newspaper decided to call it “the state highway bridge at the Austin mill.” That description was used when reporting that N.P. Shyleen, chairman of the local projects committee of the Peninsula Federated Clubs, “made his regular report at the close of which he recommended action in regard to the widening of the state highway bridge at the Austin mill. Mr. Shyleen pointed out that accidents were taking place very frequently at this point, and that something should be done on account of the danger to life and property which the bridge in its present condition, engendered.”

More sharp curve talk

The accidents at the bridge in 1933 started off with a local driver and an out-of-towner crashing into one another at the fateful corner. “The sharp curve approaching the Austin bridge was the scene of another automobile accident last Sunday. A car driven by I. C. Griffin of Bremerton skidded and collided with the car of Ivan McKenzie. Both cars were damaged but not seriously.”

Six months later, after another accident, the Gateway editor expressed long-building frustration with the situation. “The bridge near the Austin mill was again the scene of a spectacular automobile accident last Saturday evening. Accidents on this bridge are common and the cost of making repairs on broken railings must amount to considerable during a year’s time. … Much effort has been made by our different organizations to have necessary improvements made to eliminate the sharp curve at this part of the state highway. But to no avail!”

The crash in question involved Harry Steinseifer, who was, of all things, the foreman of a Pierce County bridge gang working at Rocky Bay. The June 23, 1933, Gateway described the crash. “Escaping injury after his car had plunged through a bridge railing and landed upside down 20 feet below was the experience of Harry Stiensieffer [sic] of Tacoma last Saturday. Unable to make the sharp curve approaching the Austin creek bridge, Stienseffer [sic] was forced into the railing which splintered despite its heaviness and let the car, a Buick sedan, crash down the slope below.”

In early 1934, the Gateway spread a bit of misplaced hope about the near future of the unnamed bridge. “We have it on good authority that 80 men will be put to work by the state under the CWA to improve and enlarge the Austin mill bridge, that has given us so much trouble in the past.”

There was no later mention of anything having been done to improve the bridge that year, but something was done in 1935 that at least reduced the number of accidents there.

Question No. 1. Why were so many cars driving off the side of the unnamed bridge at North Gig Harbor before 1935?

The sharp curve was blamed in several of the above-mentioned examples, but the turn onto the bridge from the west side was more sweeping and gentler than it is now, and the curve of the bridge’s east approach appears to have been slightly less severe than it is today.

Question No. 2. What was done in 1935 to reduce the number of accidents on the unnamed bridge at North Gig Harbor?

Hint: it was a major something.

Another, bigger hint: it did not involve replacing or rebuilding the bridge.

A third question could be what the clue was that finally broke my ignorance on the subject, but any discussion of my ignorance would run another 10 pages, at least. I’ll consider it a public service to avoid that.

Something new

For some strange reason, October is the time of year for spooky things and dead people. (Often times the two are one in the same.) In recognition of that, this year there are going to be eight guided tours of the Artondale Cemetery, near Gig Harbor. In recognition of that recognition, Gig Harbor Now and Then will join in with the spooky and the dead theme. On Sept. 22, our subject will be Death and Burial on the Early Gig Harbor Peninsula. Among other interesting facts, it will point out that there are dead pioneers around the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas who are not in cemeteries. They are widely scattered and mostly undocumented. That means they could be anywhere. Even under your house. Yes, your house. OooooOOOOOooh!

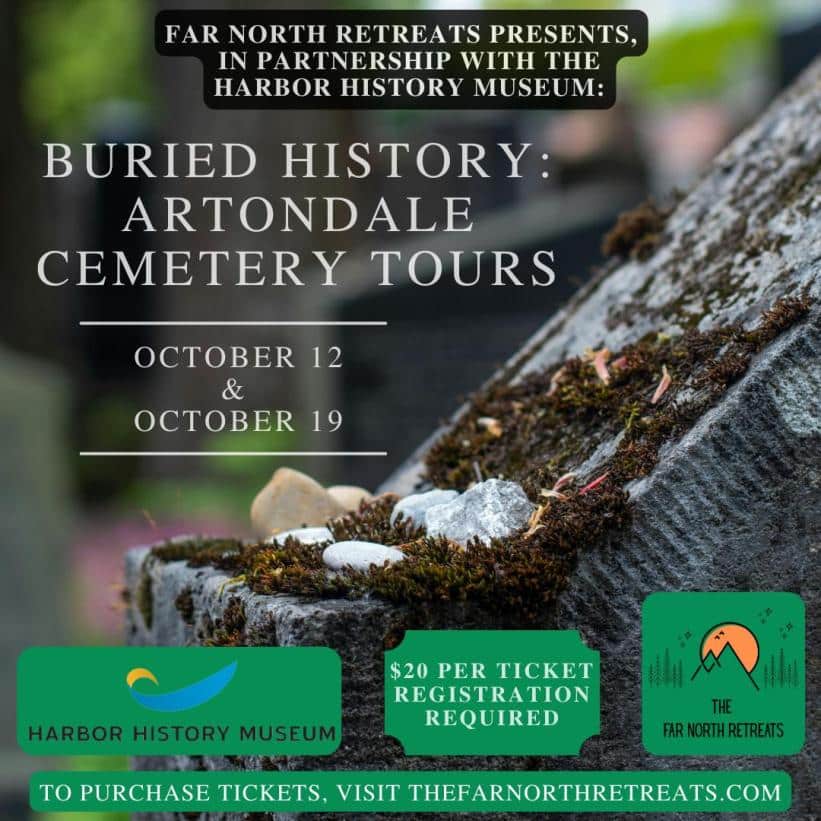

The tours are being sponsored by The Far North Retreats in collaboration with the Harbor History Museum. The event is a fundraiser for both the museum and the Artondale Cemetery Association.

Tours are offered on Sunday, Oct. 12, and Sunday, Oct. 19, with four tours each day. Two tours are offered at 1:30 p.m. and two tours are offered at 4 p.m. Each tour is limited to 20 people.

To purchase a ticket for the Oct. 12 1:30 p.m. tours, click here. At the bottom of that page are links to purchase tickets to the Oct. 12 4 p.m. tours, the Oct. 19 1:30 p.m. tours, and the Oct. 19 4 p.m. tours.

The cemetery tours run about an hour, and will feature profiles on a handful of the dearly departed, all either important figures in the early years of settlement on the Peninsula, or simply the most interesting. The list of featurees has been prepared, but I ain’t tellin’. Not because it’s a closely guarded secret, but because it may change. Their stories haven’t yet been evaluated for order of appearance or consideration as an alternate.

Being what should be the last line under the subhead Something new, this is where I’m supposed to write a smooth, snappy, or cute conclusion. As you may have noticed, I didn’t. I’m too afraid that a bad cemetery/dead people pun will escape onto the page. I definitely don’t want that. If you do, you should’ve heard them flying around at the cemetery tour planning meeting last Friday!

Next Time

Before we jump on the cemetery bandwagon (that phrase sounds just a little too festive for the subject, doesn’t it?) with our Sept. 22 column, we first have to finish today’s story. We will do that on Sept. 8, when we’ll have the answers to both of this week’s questions. They stem from the evidence I lacked for years before figuring out why so many cars drove off the side of the old wooden bridge over a then-unnamed Donkey Creek.

Also, there is a possibility that I’ll go off on a dull and time-wasting explanation of the word worstest. Although after the clumsy introduction to today’s column, that possibility is pretty remote.

— Greg Spadoni, August 25, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.