Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Smoke gets in everybody’s eyes

One of the pleasures of learning about history is the ability to retreat from the hassles and dangers of modern living by imagining yourself living in an easier, simpler time. And summer is the best time to go back to an earlier period, especially on the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas, where the pace was slower, the weather more enjoyable, and living was easy.

That’s what we’re going to do today.

We’re going to go there to temporarily forget an annual scourge of modern living, the invasive smoke from distant wildfires.

We’ll go back a bit more than a hundred years, to when the pace was relaxed, the air was clean, and the views were limitless.

Inescapable invasion

In the summer of 2025, the Puget Sound basin of Western Washington is again threatened to be visited by thin but noticeable smoke from Washington and British Columbia wildfires. With such fires more common than in the previous several decades, it’s now an annual practice to complain about the consequences suffered by people hundreds of miles from the out-of-control blazes.

“You can see a haze in the distance!”

“There’s a vague scent of smoke everywhere!”

“The mountains aren’t crystal-clear today!”

We’re no doubt being punished as a region for some undefined transgression against something or other.

It’s not just the Pacific Northwest that suffers. Earlier this year it got so bad on the country’s East Coast that on June 2, 2025, The Washington Post advised its readers that “it’s critical to know how you can protect yourself from potentially dangerous levels of air pollution” from “raging wildfires in Canada.”

We all know what it’s like. We don’t need to be reminded. What we need to do is harken back to the good ol’ days, when we didn’t have to be preoccupied with the terrible, inescapable invasion of wood smoke from beyond our northern border.

Ahh, yes, the good ol’ days. To get back to them, imagine the heavenly, soothing sounds of a gentle harp glissando, causing your vision to get wavy, just like it does on TV when they’re drifting into a dream sequence. Allow the soothing sensations to deliver you to a distant time in a familiar place, where you can take safe refuge in a far, far better world.

Photo by Ceibos, used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Your vision may be getting wavy, but don’t close your eyes during the transition, because you have to keep reading. I didn’t type all this just to put you to sleep early. Yes, I know, that’s a common side effect of Gig Harbor Now and Then, but try to fight it just this once, please? Delay your snooze to the ending? I’m not saying it will be worth making it to the end, but I finish this column by getting a little snippy for a change. Some of you might find that interesting. Maybe even refreshing.

In the good ol’ summertime

The fragrance of wood smoke in the fresh Peninsula air during the early years of settlement was a constant. Every household burned wood for heat in the winter and for cooking year-round. Logging locomotives and steam donkeys ran on wood. Sawmills throughout Western Washington burned scrap wood on open piles day and night. Steamboats used wood for fuel before coal or oil became affordable. In the cities along Puget Sound, the burning of wood created heat that powered municipal buildings, factories, water pumping, and construction equipment. There was always wood smoke rising from chimneys and stacks somewhere, even during the hottest days of summer.

Wood smoke from heating homes and buildings tapered off in the warmer months, yet summer was the worst season of the year for air pollution. It was a time when the fragrant scent of burning wood intensified to become a sting to the eyes and an ache to the lungs. The smoke from land-clear burning gone amuck and forest fires sparked by both man-made and natural causes was sometimes so thick it blotted out the sun as effectively as a heavy overcast of clouds. At its worst, it turned daytime as dark as midnight.

So common was oppressively thick wood smoke that it seldom made the newspapers. On the whole, it simply was not news. It was a regular fact of life. Only the most extreme episodes would be an event worth reporting.

Newspaper accounts of the annual “smoke season” paint a stark picture of what the people west of the Cascades had to endure virtually every year for decades. Like every other location on Puget Sound, from the Canadian border to Olympia, the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas were not spared from the all-invasive smoke. From July through September, it was common for that magnificent backdrop of countless photographs and illustrations of Gig Harbor, snow-capped Mount Rainier, to be invisible from the harbor for days or even weeks at a time, due solely to the smoke. Below is a variety of accounts of typical wood smoke events during random summers of the Gig Harbor Peninsula’s early days of settlement.

Emmett Hunt’s diary

Emmett Hunt, one of the early steamboat captains from the Peninsula, recorded his observations of the foul air in his diary on several occasions in 1885. On July 29 he wrote, “Quite warm but exceedingly smoky.” Aug. 5: “Smoke and sun about the same.” Aug. 12: “Just the same except the smoke which is worse and hurts my eyes at night.”

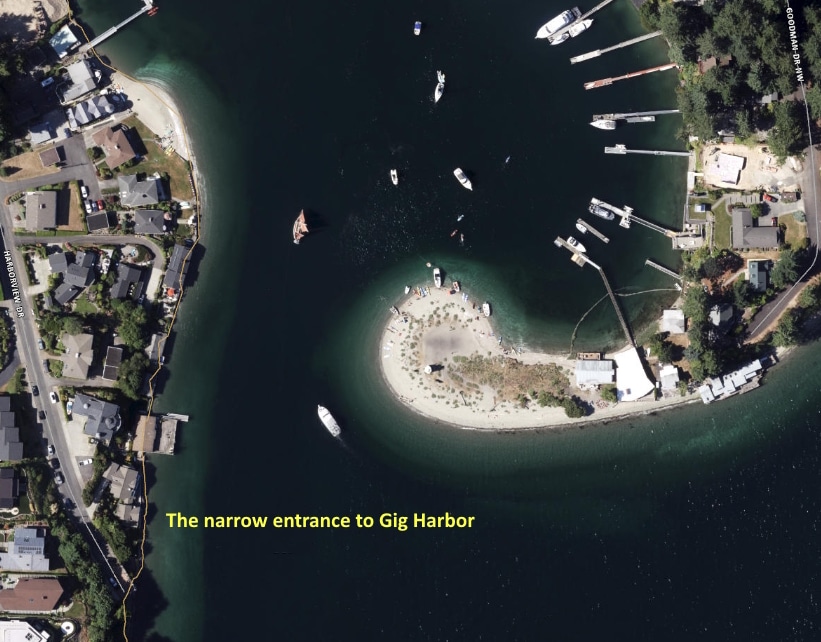

Nine years later, Hunt noted his experience of navigating his passenger steamer Victor through thick, dense smoke on Aug. 31, 1894: “Entered Gig Harbor without seeing either shore. On leaving Burnham’s I absent mindedly took a course four points wrong and soon found the beach, where we lay till the tide came back.”

Unimaginably thick smoke prevented Emmet Hunt from seeing either shore when entering the exceedingly narrow entrance to Gig Harbor. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

For readers who want to know exactly how wide the entrance is, I measured it myself:

The entrance to Gig Harbor is less than three inches wide. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Smoking Puget Sound cities

The front page of The Aberdeen Daily News from Aug. 12, 1895, reported on a typically bad year for smoke on Puget Sound:

SMOKING SOUND CITIES

Forest Fires in the Vicinity of Seattle Render Breathing Difficult.

Seattle, Wash., Aug 12. — Forest Fires in this part of the state have Caused enormous damage to property, and for the past two weeks the smoke has been so dense in the Puget sound cities that it has been with difficulty people are able to stand the stifling atmosphere. It has been several weeks since there was a rain or a shower of sufficient duration to dampen the path of the forest flames, and the fires have consequently assumed tremendous proportions.

Five days later the description of the smoke by The Seattle Post Intelligencer was no different, really, than in any one of a number of other years:

The pungent smoke creeps down the throat and up the nostrils of the people, and causes the tourists to deny the very existence of the glorious mountain ranges which are the pride of the city.

The blanket wrapped the city closer in the early hours of yesterday morning than at any time since the dry spell began, and it was impossible to distinguish a telegraph pole a block distant, while an arc light looked like a distant lighthouse at sea.

The tug Biz, which took a boom of logs from Whatcom to Tacoma, did not sight a steamer on the whole trip … The same condition prevails along nearly the whole coast, for the steamer Walla Walla, which came from San Francisco yesterday, reports smoke as far south as San Francisco.

Mark Twain weighs in

Samuel Clemens — the real name of America’s most famous humorist at the time, Mark Twain — was on a world speaking tour in that same year of 1895. In our state he was lecturing at Olympia, Tacoma, Seattle, and Whatcom during the month of August, at the height of smoke season. The manager of the North American leg of the tour, Major J. B. Pond, wrote of the smoke on Puget Sound in his book, “Eccentricities of Genius,” when describing Tacoma. “This is another overgrown metropolis. We can’t see it, nor anything else, owing to the dense smoke everywhere.”

Pond also related an exchange between John Miller Murphy and Clemens in Olympia:

“Mr. Twain, as chairman of the reception committee, allow me to welcome you to the capital of the youngest and most picturesque State in the Union. I am sorry the smoke is so dense that you cannot see our mountains and our forests, which are now on fire.”

[Clemens] said: “I regret to see — I mean to learn (I can’t see, of course, for the smoke) that your magnificent forests are being destroyed by fire. As for the smoke, I do not so much mind. I am accustomed to that. I am a perpetual smoker myself.”

Nothing new

The Seattle Daily Times reminded its readers on Aug. 3, 1898, that the smoke season was nothing new: “Forest fires are raging at a great rate at present, and the atmosphere is getting thick with smoke. It is an annual occurrence on the Sound and old-timers expect it at this time every year.”

A very bad year

The forest fire season in Western Washington started early in 1902 which, because it did not end equally early, made for the worst smoke conditions most locals could remember. By September, The Seattle Daily Times reported smoke so thick on Puget Sound that very few cargo ships dared sail through it. The local passenger steamers continued to run, though some were late, “owing to the slower speed necessitated by the thick atmosphere.” The newspaper further described the situation on the water:

From officers on the incoming steamers of the Sound fleet it is learned that the pall of smoke extends to all parts of the Sound. The routes for the full run in each direction as far as Sound steamers run is made in the total darkness similar to that which overhangs the city and harbor. The passenger steamers keep their lights burning with consistency. Lights without as signals accomplish but little or no good, as they are visible no further than the forms of the vessels carrying them.

“It is the worst ever seen on the Sound,” is the universal verdict of shipping men. Other forest fires have occurred in past seasons and charged the atmosphere heavily with smoke, even to the extent of making navigation inconvenient and unsafe, but there has never been anything like the present darkness in the memory of the oldest Puget Sound navigators. For years to come, probably, it will remain memorable in the history of the Sound as the “big smoke of 1902”.

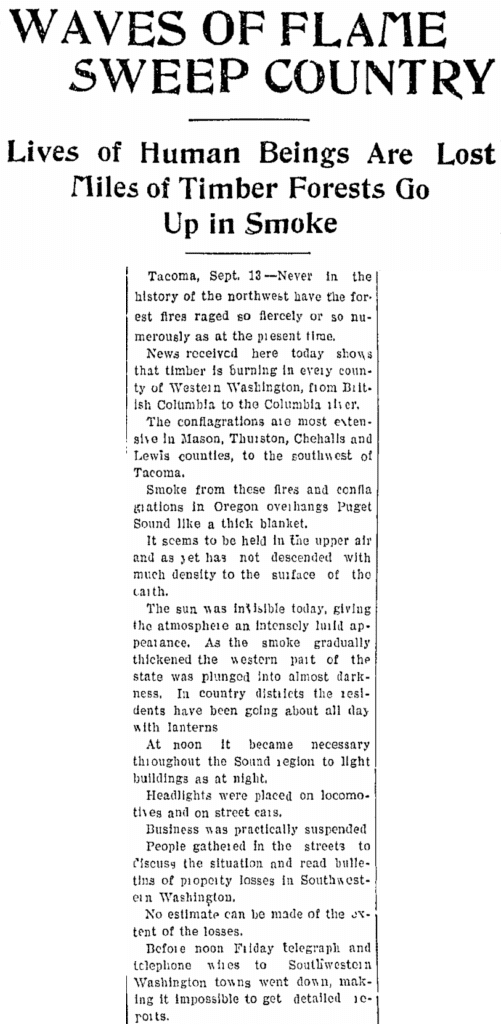

When especially bad, stories of the smoke season were reported around the country. The Evening News in San Jose, California, noted on Sept. 13, “As the smoke gradually thickened the western part of the state was plunged into almost darkness. In country districts the residents have been going about all day with lanterns. … At noon it became necessary throughout the Sound region to light buildings as at night.”

The San Jose Evening News on Sept. 13, 1902.

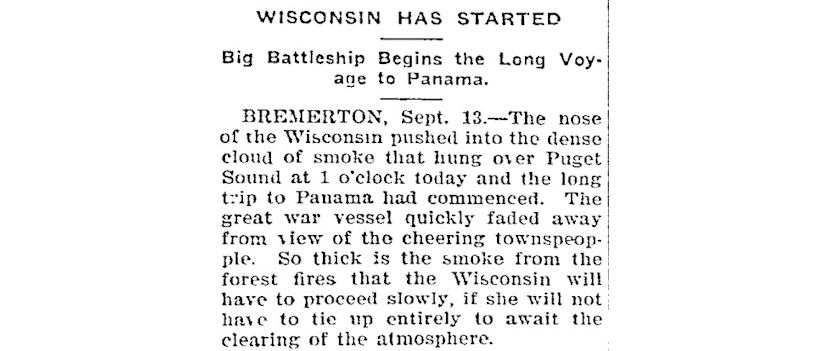

Even the U.S. Navy had trouble maneuvering one of its battleships through the smoke. The Morning Olympian, September 14, 1902, page 1.

Armageddon

In a front-page story, also on Sept. 13, The Morning Olympian claimed the smoke season of 1902 was not the worst ever encountered on Puget Sound. “The memory of the oldest inhabitant was invoked yesterday for a precedent for the dense smoke … In 1847 for a period of six weeks darkness reigned unbroken; rivers ran thick with ashes and a mantle of ashes covered everything. Many of the people almost went blind on account of the smoke, and many feared that the end of the world had come.”

Waxes and wanes

After a less intense smoke season in 1903, the fires of 1904 were again a serious problem. The Seattle Daily Times’ reporter in Tacoma wrote, “A lurid haze covers the landscape here this morning and the sun can scarcely be seen. Forest fires of greater magnitude are burning in the county than have existed since the great fires which two years ago carried away hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of Washington timber.”

As for how the Gig Harbor area was faring, The Times said, “The forests in the neighborhood of Gig Harbor and Artondale are burning, and have been for several days. These fires … originated through farmers burning slashings.”

A one-year respite

Due to a collapsed lumber market in 1907, most logging camps in the Puget Sound region — the accidental source of many fires — were shut down all summer, resulting in the lowest damage due to forest fires in 19 years, and presumably a correspondingly reduced smoke season. But Gig Harbor wasn’t entirely spared. “Across the Narrows a fire is burning in the woods in the suburbs of Gig Harbor, and the people of that place are very uneasy,” said The Seattle Daily Times.

Logging picked up in the following years, and so too did the summer fires and smoke.

Efforts to reduce the danger

Although the forest fire and smoke problems continued in Western Washington year after year, it was not as if nothing was being done to try to solve them. Various associations and governments took steps to prevent forest fires and to fight them when they did break out.

Because many of the wildfires in Washington were caused by sparks and glowing embers escaping from the stacks of steam-powered locomotives and logging engines, the state passed a law in 1903 requiring spark arrestors on all steam engines used for logging in Washington forests during the fire season.

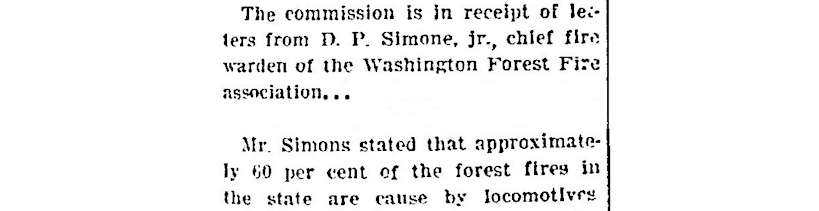

Progress with spark arrestors appears to have been slow, however. In 1910 the warden of the Washington Forest Fire Association said that about 60% of the forest fires in the state were caused by sparks emitted by locomotives.

Locomotives were said to be the cause of 60% of all forest fires in Washington state. The Morning Olympian, June 15, 1910, page 1.

Many landowners and timbermen had voluntarily adopted the practice of burning logging slash (limbs, tops, and broken and uprooted brush) to reduce the fuel available for forest fires, which protected neighboring stands of timber that had not yet been cut. Sometimes the slash fires escaped containment, causing problems of their own, but by and large it was an effective tool for reducing summer fires. As a refinement to the practice, the Washington Forest Fire Association launched a publicity campaign in 1909 to encourage timber owners, loggers, and farmers to burn slashings before the hot, dry weather of summer. It adopted the slogan Burn Now, and issued a bulletin stating its case:

Avoid forest fires, unnecessary smoke and injury to the soil by burning slashings during the month of May, while there is little or no danger of injuring other property, and prevent needless smoke after June 1, when visitors will begin coming West to view our scenery and the A. Y. P. exposition.

The A.Y.P. was the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the first world’s fair held in Seattle. The organizers were so concerned about the annual smoke problem in Puget Sound that they had attempted at the beginning of 1909 to get a law passed through the state Legislature outlawing the burning of slash, but were unsuccessful. The Washington Forest Fire Association’s campaign was their next best hope. While it may have helped a little, on the whole it was a failure. The summer of 1909 was another bad one for smoke on Puget Sound. On September 8, The Seattle Daily Times wrote,

It is to be regretted that the long absence of rain has permitted “forest fires” to spring up everywhere—causing a dense smoke to settle down over all the land and water—and thus preventing the visitors at the A.-Y.-P. Exposition from gaining any proper impression of the splendid beauties surrounding Seattle. The Olympics have not been seen in a month, and Mt. Rainier has disappeared altogether. Two days of rain would put out the forest fires and clear the atmosphere, and it is to be hoped that the twenty-first of September will witness both.

The hoped-for rains did come, and the atmosphere was cleared, but the scenic views of the Cascade Mountains lasted only a single day.

The Seattle Daily Times on Sept. 4, 1909.

After one brief day’s view of the beauties of Mount Rainier, which was enjoyed by visitors to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition yesterday, heavy clouds again surrounded the mountain.

The great peak, when it became visible yesterday, after weeks of obscuration by the smoke of countless forest fires, was viewed and admired by thousands at the exposition.

Gig Harbor gravely threatened

Even more forest fires and smoke darkened Puget Sound in 1910. It may have been Gig Harbor’s worst year ever, for the north end of town looked as if it would be totally destroyed by flames working their way south from on top of Peacock Hill. On August 25, The Seattle Daily Times summed up the situation in the Tacoma-Gig Harbor-Vashon Island area: “Telephone communication with Gig Harbor is cut off because of a forest fire raging on the mainland near Gig Harbor. A large fire is burning on the north end of Vashon Island. Tacoma is overhung by a pall of smoke. The sun did not appear this morning, although there are no clouds.”

Only a shift in wind direction saved the town of Gig Harbor. Though it was spared, it continued to choke on the smoke from dozens of other fires still raging along the shores of Puget Sound and miles inland.

Non-forest smoke

There was one more source of smoke that Gig Harbor residents were forced to put up with sporadically throughout many years. A big ore smelter in Ruston, immediately east of Point Defiance, belched out thick, smelly, acrid smoke day and night. The industrial exhaust was so unpleasant that it became a liability for home sellers in the north end of Tacoma. One real estate company mentioned it to good effect in its advertising for building lots south of Tacoma: “Take that little family out away from the stifling smelter smoke where the air is PURE and FRESH.”

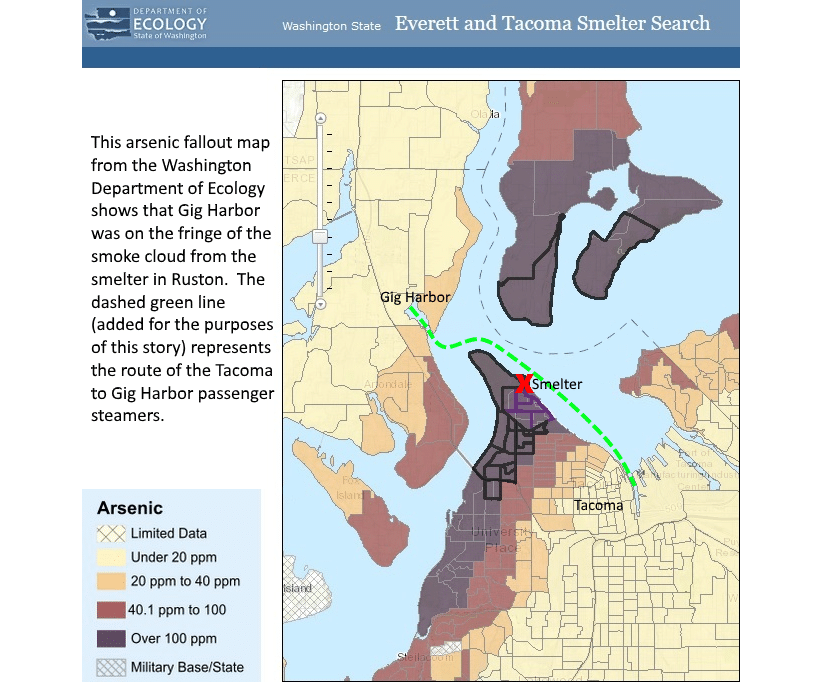

The dashed green line (added for the purposes of this story) on this smelter fallout map shows the route of the downtown Tacoma-Gig Harbor passenger steamers. Washington State Department of Ecology map.

Though the prevailing winds mostly carried the foul stuff north to Vashon Island and somewhat less often south, on occasion it was blown west to the Harbor. The Gig Harbor residents most affected by it were the commuters on the passenger steamers, who, depending on the wind currents, sometimes encountered it twice a day. The boats running between Gig Harbor and Tacoma passed by the smelter near the halfway point of the run, occasionally plowing through the offensive odor before steaming into clean air.

The random risk of smelter smoke was a staple of the Gig Harbor-Tacoma route for passenger steamers from 1887 until the building of a taller smokestack in 1917. That didn’t reduce the amount of sulfur dioxide odor or the toxic heavy metals it carried higher into the air, including lead, mercury, cadmium and arsenic, but it did serve to scatter it over a wider area, somewhat diluting the effects in any specific location.

Cue the harp

Unfortunately, just as the harp takes you away to the past, it also brings you back to the present. The miserable, unbearable, insufferable present, where vague whiffs of wood smoke and visible haze in the far distance is a constant reminder of how very bad we have it today compared to the purity of Peninsula air over 100 years ago.

The Gig Harbor Now and Then soapbox

Having done land-clear burning for years as an employee of Spadoni Brothers — with machines that did not have enclosed cabs — I know what it’s like to work in wood smoke so thick you can’t see from one side of a piece of property to the other. But that was only on days when blustery winds prevented the smoke from going straight up.

Uncooperative smoke in Crescent Valley in 1996. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

And even at its worst, which was so bad I couldn’t see the front of the machine I was operating, the smoke never affected my breathing. It was not choking, and never made me cough. It sure made my eyes water, though. That was my canary in the coal mine. When my eyes started stinging and watering, it was time to work the burn pile from a different side, or do some dirt work for a while until the smoke was moving in a different direction.

Today my sympathies lie entirely with people who have existing respiratory problems. They can be seriously affected by conditions that the rest of us wouldn’t even notice, were they not urgently broadcast by attention-seeking news outlets.

While the bulk of the modern-day trace-of-smoke complainers appear to try to imply the direct opposite, to me they are simply proving how easy their lives really are. Walk a mile in my smoke-soaked boots and then tell me how bad you’ve got it today.

On that friendly note, today’s topic is concluded. And I didn’t even take the opportunity to point out what it’s like to work in thick, blue asphalt smoke while paving roads. But that rant is probably coming up sometime in the future, assuming we can all survive the occasional faint whiffs of wood smoke this summer.

Next time

On Aug. 11 this column will take a brief but interesting (I hope) trip to 1953. The mini-vacation will be confined to three weeks in May of that year. Why? Because I impulsively acted on a vague, potentially dumb idea without thinking it through, that’s why.

If that leaves you scratching your head, imagine how the editor must feel. I haven’t showed it to him yet, either.

— Greg Spadoni, July 28, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.