Arts & Entertainment Community

State’s new Poet Laureate found his inspiration in Gig Harbor

Washington’s eighth and newest Poet Laureate, Derek Sheffield, hails from right here in Gig Harbor, where he was first a student at Gig Harbor High School, and later returned to teach.

It was Sheffield’s teacher, Kevin Miller, who showed him how poetry could light up one’s whole being; it was the Harbor who taught him to become a poet. Gig Harbor Now’s Carolyn Bick recently chatted with Sheffield, who now lives in the Wenatchee Valley, about how the Harbor and his work as a teacher shaped and continues to shape his poetry, and how becoming a father added a new dimension to his poetry.

The governor appoints Poet Laureates to two-year terms based on the recommendations from a panel of nominees. Sheffield will serve from 2025-2027. The program is sponsored by Humanities Washington and ArtsWA.

Gig Harbor Now: So, I read some of your poems from Not For Luck, and a few on Poetry Foundation, and also checked out Terrain.org, the online literary publication for which you edit. I really wanted to just jump right in and ask how you came to focus on poetry at once steeped in the natural world and firmly pressed against humans’ creations.

Derek Sheffield: That also goes back to Gig Harbor. I think that coming up in such a place really marked me — I was marked by place in coming up there.

When I was a kid, we were in a little housing development. I didn’t really know about the waterfront part of Gig Harbor, because we were in this little housing development in the woods off of Rosedale. But that was great. We got to roam around these second-growth woods and stuff.

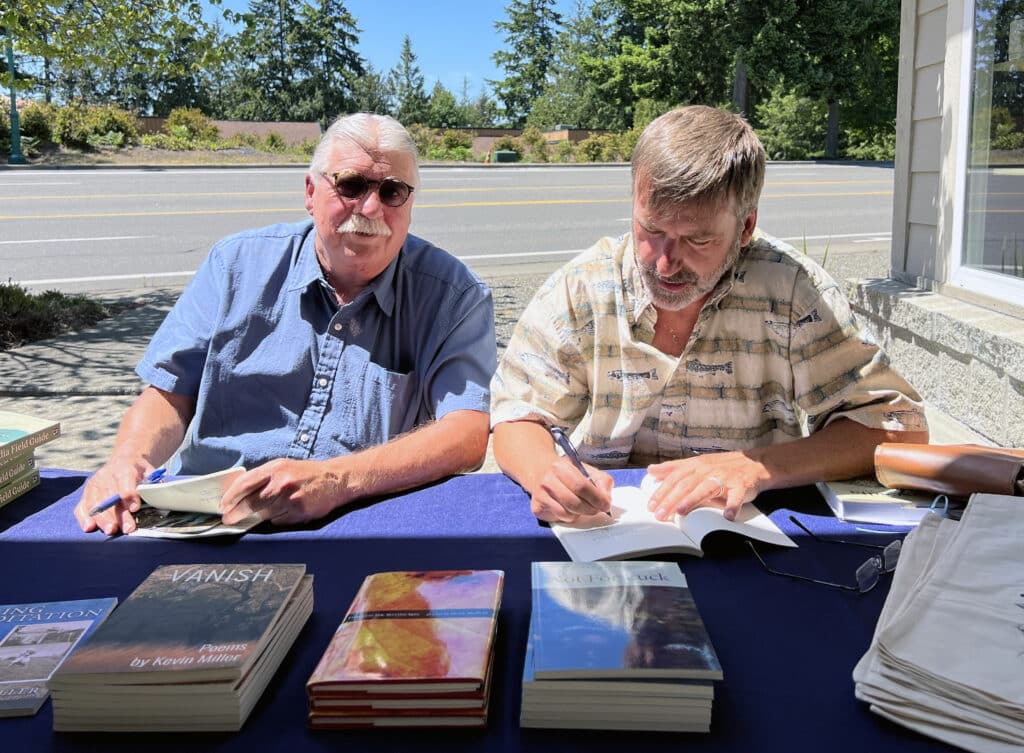

Derek Sheffield, right, and his former Gig Harbor High School teacher Kevin Miller sign books outside the former Invitation Bookshop location in 2023. Sheffield is the Washington State Poet Laureate for 2025-27. Photo courtesy Derek Sheffield

I think that was important, but even more important was when I went back to teach at Gig Harbor [High School]. I was a student there, and then I came back to teach. And when I came back to teach, I was able to rent an old boat house at the bottom of a steep cliff in a place called Shaw’s Cove near Horsehead Bay. It looked right at Fox Island and Mount Rainier.

I was starting to teach, which is just a lot of work. I was living alone. I was the only person down at the base of this steep cliff. It was a boat house that had been made into a studio apartment.

I was working my tail off trying to learn the curriculum just ahead of my students, trying to learn how to teach. I didn’t have television, because I was trying to pay off my student loans. And there was this colony of pigeon guillemots next door to me, but I didn’t know who they were. They just, they were like this black bird with these weird orange feet — you know, like, “Whoa!”

And then I started looking around me and I could identify gull and crow and duck — but, oh gosh, so woefully inadequate. Through those gray rains of winter, living alone, working really hard, I found great solace in all the waterfowl. That’s the beautiful thing about the harbor and the Salish Sea. There’s that migration where we actually have all those waterfowl down from Alaska for the winter — surf scoters and common loon and red-necked grebe and horned grebe and these amazing birds.

And then of course, there was gray whale and seal, and when I say landscape, I mean also seascape. I mean the living world. The living world there was essential company for me. And it’s where I really felt the first deep stirrings of biophilia.

A poem by Derek Sheffield, reprinted with his permission.

Island View Market

The owners have taped twenty years

of hands-in-pockets to a fridge

buzzing in the corner behind the candy,

neighbor kids I can almost name.

I never stuffed my fist with change,

hopped on a bike and rode

to scatter Jolly Ranchers and lollipops

onto the counter, betting I had enough.

I never walked my bike back, blowing spit

from a candy whistle. Who knew

it would matter to be lined up a life later

with other awkward smiles, lime-green shirts,

bad haircuts, and hats of losing teams?

A boy on the road scruffs the stray gravel

as I pass, working a popsickle stick

in his mouth. When they take his picture

he is looking somewhere else.

GHN: How old were you?

Sheffield: I was 26.

I’m a kid of the ‘80s and the Harbor was the sleepiest, most boring place. I mean, there was not even a fast food restaurant in the Harbor when we grew up there.

I remember it was, I think, my senior year when Dairy Queen first arrived. I think Dairy Queen was the first one. Before Dairy Queen, there was a place called, I think, John’s Breakfast and Burgers — something like that. That was a kind of independent fast food place, but no chain fast food store, until Dairy Queen arrived.

It was so sleepy. You would go into town on the weekend and it was just you and the fog and the gulls. The chamber of commerce had this massive outreach going on with the bumper stickers — “I’d rather be in Gig Harbor.”

[The bumper stickers] were everywhere. They were trying to get people to move to Gig Harbor — “Hey, come to Gig Harbor!” And boy, were they successful.

GHN: Yeah, really! The way you just described it honestly reminds me of Stephen King’s ideal settings for all of his novels — always in Maine, always this tiny little sea town with lots and lots of fog, and then something terrible happens.

Sheffield: Yes, yes, except that the only thing that was terrible that happened is Walmart came to town. That was the horror.

To go back to your original question: The land and the seascape were my closest company through that first long winter. And they were essential. It’s hard to explain — like the living world became a lifetime friend.

I was like, “Oh my gosh! I’ve had this family member here all along. And I didn’t know.”

My sister bought me a pair of binoculars and I bought the Audubon bird guide and I started learning all the birds. I started learning their names, because I realized how incredibly ignorant I was.

I realized how incredibly ignorant I was, but only after I understood how incredibly important this life was, these birds were, that were there with me all winter through the cold and the gray and the wet.

GHN: So it sounds to me like you snapped out of your human-centric view of the world.

Sheffield: Oh, you must be a reporter or something. That’s such a pithy way to put it.

GHN: [Laughs] Thank you. Not only am I a reporter, I know exactly what you mean because that happened to me way back in when I was a kid playing with cherry bombs [Author’s Note: These were the seeds of the sweet gum tree, and usually colloquially called “gum balls.”] So I know exactly what you mean. There are so many people here who aren’t human. It’s great. It’s a great feeling when you get to talk to everybody, too.

Sheffield: Oh, yeah. I mean, the animacy of the living world — I don’t know, maybe you don’t realize how much harm the Cartesian worldview is doing until you really feel and know the animacy of the living world. T the Harbor let me do, let me feel that.

Derek Sheffield hiking at Mount Saint Helens. Photo courtesy Derek Sheffield

I do make pilgrimages back periodically. I don’t get back there very often, but I was back there last summer for a tennis team reunion in June. Tennis players from Peninsula High School and Gig Harbor High School got together, and we played tennis and pickleball and caught up, and our old superintendent, Tom Hulst, showed up.

There’ve been other reunions. When my daughters were growing up, I wanted them to know something of the Harbor, so I took them there, but I don’t get there a lot.

And when I do get there, I feel like it feels like sacred ground to me, maybe the way one’s — hopefully — one’s home place always feels to one. Maybe it’s because my family moved away, as I graduated from high school, and so, in a sense, it was taken away from me.

I think that when I am able to go back, it feels really special. It feels sacred.

And, of course, you drive through the halls of memory.

I knew George Borgen. My dad was good friends with him. He was Mr. Gig Harbor, the community spirit of Gig Harbor incarnate. Borgen’s Building Supply — I still have a dish strainer from Borgen’s Building Supply for pasta.

A poem by Derek Sheffield, reprinted with his permission.

The Pigeon Guillemot

Odd, sooty children raise me

through morning shades with their seeking

and hiding along the wave-stilled beach,

whistling out their shrill, stretched necks.

Glissading down on stubby, white-specked wings,

sun-slipped from cliff and crevice,

they assemble for the chase, balance on driftwood

and squeal like a circus of pinched balloons.

Jesus walked. These fowl sprint, orange feet

splattering a rippled runway into flight.

They wobble among rocks, peek

from the chop and plumply pipe the weather

before lighting to their daily fish.

I turn to the verse of their wakes, mark the ink

of their plumes as they dive—saved

by each clownish foot.

GHN: Speaking of Gig Harbor and coming back and going and leaving again and so forth, I wanted to know whether your time, not just in the rest of the natural world, but also as a teacher or as a student impacted or influenced your work in any particular way, especially given your stated focus on the mental health of young folks.

Sheffield: Yes. So, two-part answer to that.

First off, when I started out talking about how I wouldn’t be here talking to you in this capacity without Gig Harbor, what I meant was not just the place itself, but also the teachers at Gig Harbor High School.

There was an incredible group of teachers who had a kind of utopian vision of education, who had come from the Peninsula. I think Gig Harbor [High School opened] in like 1980, maybe, ’81 (actually 1979).

It was brand-new when I got there, and people like [Pamela] Wise were essential to me surviving being 16 and becoming an English teacher.

Not just Pam Wise, but also Kevin Miller. Kevin Miller was the guy who really got me into poetry. Before him, I wanted to either own Mostly Books or I wanted to be a writer and write books like Stephen King and Edgar Rice Burroughs, and all these other authors that I was gobbling up. But I had a class of short fiction and poetry with Kevin Miller, and I saw how poetry lit up his whole being.

I was like that woman in “When Harry Met Sally” — “I’ll have what he’s having.”

People who knew Kevin Miller would just say about me now, “Oh, Sheffield, he’s just doing his best impression of Kevin Miller as he goes on, and he’s Poet Laureate-ing around the state.”

We had an incredibly special group of teachers there. Terry Parker for drama. I could go on listing them, but Kevin Miller, especially, was my mentor and continues to be one of my closest friends to this day.

As I do this work for the next couple of years, I aim to pull him out of retirement and get him in the spotlight.

The second part of your question was when I considered applying for this position [of Poet Laureate] back in the fall, I thought, “Well, I could do some work in eco-poetry and in raising ecological consciousness.” I’ve been doing that already with Cascadia Field Guide and the other poems and so forth.

But then I thought, “Well, you know, Rena Priest, who was a terrific Poet Laureate, did that with her book called Singing the Salmon Home. And I thought, “Well, I don’t want to just repeat Rena’s path there.”

And so, my question to myself was “How can I help? How can I be of service? How can I use this role?”

I know I’m going to raise awareness for poetry in our culture, and that does good work, but how can I really help? And I very quickly thought of my students at the college and what I’ve been seeing the last four or five years, really since the pandemic.

And I thought about my own daughters and I knew immediately that I wanted to use poetry as a way to address and normalize mental illness and to nurture mental wellness in young people.

When you read poems, when you write poems, when you are in the world as someone who does those things, you slow down and you become reflective and you can start to value your inner life instead of the miasma of the online life that we know that’s going on out there. You tend to pick sky time over screen time.

I see a mental health crisis. Some young people are aware of it and are seeking help. Others are not aware of how much help they need.

And maybe this manifests down the road, but that’s what I wanted to do. Poetry gives us all kinds of things. I take very seriously the craft that goes into poetry, making poems. I think all of us are drawn to poetry because we get a bit beat up in this living.

It just happens. It’s like Leonard Cohen singing about the breaks are where the light gets through, you know? And then there’s Nietzsche who says that living is suffering.

It’s part of that, that suffering, that hurt as part of the deal. I think language and poetic language in particular can put us in touch with something greater than ourselves, like maybe no other kind of art form — maybe music, but I don’t know.

I think in some homes and some parts of our culture, there’s still some stigma about mental illness and even just taking steps to ensure mental wellness. That still is not seen as really important or as being equivalent to physical health. Which, of course, is just ridiculous because we know that one is the other.

Mental health is physical health. Physical health is mental health.

GHN: That’s actually a really good segue because you touched on this a few minutes ago in your response.

I had noticed that several poems of yours talk about family, your daughters, in specific. And what really stuck out to me was that there was almost like a questioning air to them — like you were really curious about what was going on in their inner worlds, but couldn’t really tell and could therefore only relate or speculate externally, which obviously makes sense, but it was really interesting in the way you did it.

First of all, I wanted to make sure I was reading that right. And also if that is right, if that relates back to your focus on the mental health of young people.

Sheffield: I think that that is a fine perception. Yes.

I think that another reason maybe I’ve come to this work and this role is that I paid quite a bit of attention to my daughters growing up.

I was just in awe of their imaginations and still am. I didn’t think of myself as being a father when I was younger. I’m so glad that I did become one. The subtitle for Not For Luck would be On Daughters And Other Wild Things.

To have the kind of access to their state of grace — of innocence; I said grace. I meant to say innocence, but that’s a Freudian slip — to their state of innocence, to have that kind of access to it as a parent, as someone who had been developing this poetic sensibility in myself, because poetry is not just about words on the page.

It’s about, it’s a way of being in the world, for goodness sake. It’s everything. It informs everything. Everything is part of it. It is part of everything. And so I had this poetic sensibility nurtured in me, before I became a father, and then the most poetic things of all came into my life in the form of these two little critters. And again, to have the kind of access to that state of innocence was a marvel. It was a marvel.

It was a grace and it’s gone now. Mary Oliver, who is one of the poets I return to again and again, said that attention is the beginning of devotion. And little did I know what was happening in me as I attended so carefully to the moments of their lives.

[Pauses.]

And boy, speaking of Gig Harbor — it was wild. Maybe six or seven years ago, I suddenly had this powerful bout of regret that I wasn’t raising my daughters in Gig Harbor. Again, because Gig Harbor feels like sacred ground to me.

I don’t know what it was that triggered this. Maybe because I had some friends, some old classmates, who were living there and they were doing that. They were raising their kids.

They were doing the old rituals that we did — like, “Okay, now you gotta jump off the Raft Island Bridge.” And all this stuff that was part of the nature of that place. And oh, my gosh, I had this just powerful sadness and regret that I wasn’t raising my daughters there.

It took a while to get past that and to understand that the Gig Harbor that exists now is mostly very different than the one I grew up in. I started to think about Leavenworth here, the boondocks outside Leavenworth, as their Gig Harbor because they had a rural childhood, kind of like I did — semi-rural, I guess.

GHN: So, with the Freudian slip, I wanted to ask: Is one of your daughters named Grace?

Sheffield: No, no, but close. Zoey, which, of course, really goes back to that first year in Shaw’s Cove, when I became a biology geek and an amateur naturalist. Her name is from “zoology.” Her name means “life.”

And then her sister’s name is Kelsea — K-E-L-S-E-A. And she’s the younger one.

Kelsea, the word means “of the sea.” So, together, the two of them spell “life of the sea.” And it’s kind of a poetic homage, I think, to the harbor life of the sea.

It’s funny because I actually was lobbying for Kestrel or Phoebe — a couple of bird names. Kelsea was a compromise and now I realize it worked out perfectly, just as it was supposed to.

GHN: Finally, do you have any recommendations of poets readers should check out, if they like your work?

Sheffield: Yeah. Mary Oliver, William Stafford, Naomi Shihab Nye, Kevin Miller. Then there’s a terrific Tacoma poet named Allen Braden.

Gary Soto — he was one of my favorite poets growing up. And he writes so compellingly about growing up as a first generation Mexican American picking fruit and working row crops around Fresno. Just a great writer and a beautiful person.

Ross Gay is just really exciting — his poems and his prose.

I love Li-Young Lee. And Paisley Rekdal is pretty incredible.

Oh, my gosh. Lucia Perillo. She lived in Olympia. Oh, my gosh. She’s amazing.

Oh, oh, jeepers creepers — Ellen Bass — my friend Ellen. And Mark Doty. And Jane Hirshfield.