Business Community

Cushman dams now produce more history than power for PenLight

The Cushman hydroelectric project once was Peninsula Light Company’s sole source of power. Now it’s just one piece of a much larger energy puzzle.

The local power provider and the Cushman dams are historically entwined. Tacoma Power began building its first dam on the north fork of the Skokomish River in 1924. It planned to string transmission lines from Potlatch on Hood Canal to the city, running through the Gig Harbor and the Key Peninsula areas. Locals created a utility to tap into them.

They founded the member-owned cooperative Peninsula Light Company in July 1925. The first dam began generating electricity in 1926. Tacoma Power added a second dam 2 miles downriver in 1930. The project energized PenLight members for 50 years.

PenLight buys it power from BPA

Today, PenLight buys all its electricity from the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), a federal agency that markets power from a network of Northwest dams, said spokeswoman Britni Wickens and Chief Operating Officer Amy Grice.

Cushman is not part of BPA but provides about 6% of Tacoma’s energy supply, said Tacoma Public Utilities (TPU) spokeswoman Jessica Wilson.

A 1976 court decision allowed PenLight to use Tacoma’s Power’s transmission system to switch to its first federal electricity from BPA. Because TPU sends power to PenLight through that agreement, and Cushman is part of TPU’s energy mix, some Cushman electricity makes its way back to the peninsula. It’s impossible to say how much.

“Physics does not allow for us to isolate BPA electrons from TPU electrons,” said PenLight Director of Energy Resources Jacob Henry. “As such, depending on local loads and if TPU’s hydro facility is generating or not, it is possible our power is coming from Cushman. So, on paper we receive all our power from BPA. That is who we buy it from. Tacoma on paper wheels that energy from BPA to our loads. BPA and TPU work together on a regional level to maintain load/resource balance as they both act as independent balancing authorities. Physically, the electrons that serve our members come from the regional electric grid, and we cannot control where those electrons come from or go.”

Demand exceeds potential Cushman supply

Many people, such as several who commented on a couple recent power outages, still associate all local power with Cushman because of its historical significance and visibility. But today’s electricity mix is far more diversified and regionally interconnected, said Wickens and Grice.

Even if PenLight wanted Cushman to power the peninsula, its dams don’t produce enough electricity to meet the increased demand.

“Today, Cushman still generates electricity, but it contributes only a portion of the power used by PenLight customers,” wrote Wickens and Grice. “Even at full generation capacity, the Cushman Project could not provide the peak load of the PenLight service territory. … While local sources like Cushman laid the groundwork, today’s grid is powered largely by BPA’s hydroelectric system.”

Combined, the two Cushman dams can power about 25,500 homes, according to TPU documents. PenLight now serves 32,310 members, Wickens said.

Though mostly hydro-powered, PenLight receives a portion of the energy generated from the Harvest Wind Project, a wind turbine farm near Goldendale that can generate enough renewable power for more than 23,000 homes.

Some power comes from wind farm

It partnered with three other Northwest public utilities to build the project, which was completed in 2009, largely to comply with the Energy Independence Act. The 2006 state law requires utilities to acquire a growing share of energy — now 15% — from renewable resources that are not hydropower.

Power moves back and forth between Tacoma and the peninsula through the Narrows transmission lines, which are also connected to the broader BPA transmission system. Electricity flows 40 miles from Cushman to a large TPU substation at 21st and Pearl streets.

Tacoma Power, the PenLight supplier, also sends power back to the peninsula. The electricity is routed to eight PenLight substations, where it’s transformed from high voltage to medium voltage for distribution to neighborhoods.

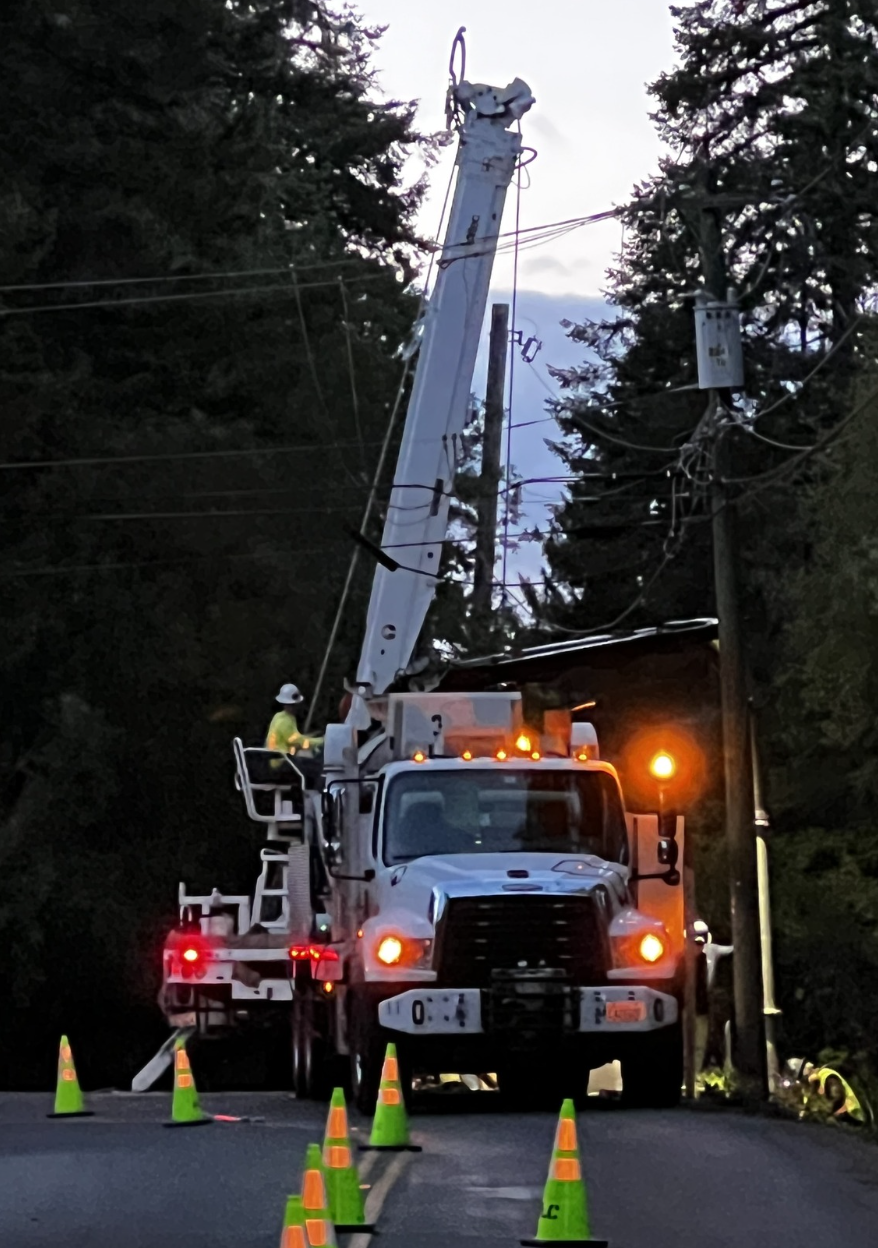

Transmission lines cause largest outages

Major PenLight power outages, like one that knocked out the entire system on April 25, usually involve the high-voltage transmission lines. That day, an equipment failure occurred when TPU workers performing routine transmission maintenance caused a line to ground fault, said TPU’s Wilson. Tacoma Power restored transmission service to Peninsula Light and all but a few members had their lights back on within 2 1/2 hours.

PenLight has two “taps” into the Tacoma Power transmission line. One runs from the Cushman Trail down past Artondale Elementary, and the other serves the entire Key Peninsula, Grice said previously. Impacts to that part of the system can cause larger outages such as occurred March 19, 2024, from a car accident that damaged a transmission pole and affected more than 20,000 members.

Less widescale outages can happen when problems arise at a substation, like on Thursday, May 15, when the Gig Harbor station experienced an equipment failure. About 5,700 members lost power for 2 hours.

Even smaller outages transpire when tree branches or wayward cars damage equipment between substations and homes, such as Saturday, May 17, when a broken pole was discovered on Fox Island. That took twice as long to restore as the larger outages because the pole had to be replaced.

After large outages such as on April 25, PenLight must wait for Tacoma Power to complete its repairs before it can begin routing power and bringing up substations. When a total or near-total outage occurs, power is not restored all at once, which could overload the system and risk further damage, Wickens and Grice said.

Get the most people restored in shortest time

PenLight’s goal is to restore power safely to the most members in the shortest time. Tens of thousands of people could be served by one transmission line, so it draws first attention. Then crews address substations, which each serve thousands of members.

Next in order are main distribution lines that carry electricity away from a substation to a town or housing development. Critical sites such as hospitals, schools and water systems, followed by major retail centers that have gas stations and grocery stores, receive priority.

Crews continue restoring outward to tap lines that carry power to utility poles or underground transformers outside houses or other buildings. PenLight also tries to equitably restore power between the Gig Harbor and Key peninsulas.

Twenty years ago, PenLight was rated among the least reliable utilities in the region. It struggled to keep power on and was slow to reboot it when it went off. After focusing on becoming more dependable, it’s now among the top 25% despite serving a heavily treed territory.

Members incur fewer outages for shorter times because of improvements such as undergrounding 80% of power lines, replacing overhead lines with more durable cables, trimming branches away from lines and upgrading old meters with higher-tech ones that immediately detect outages.

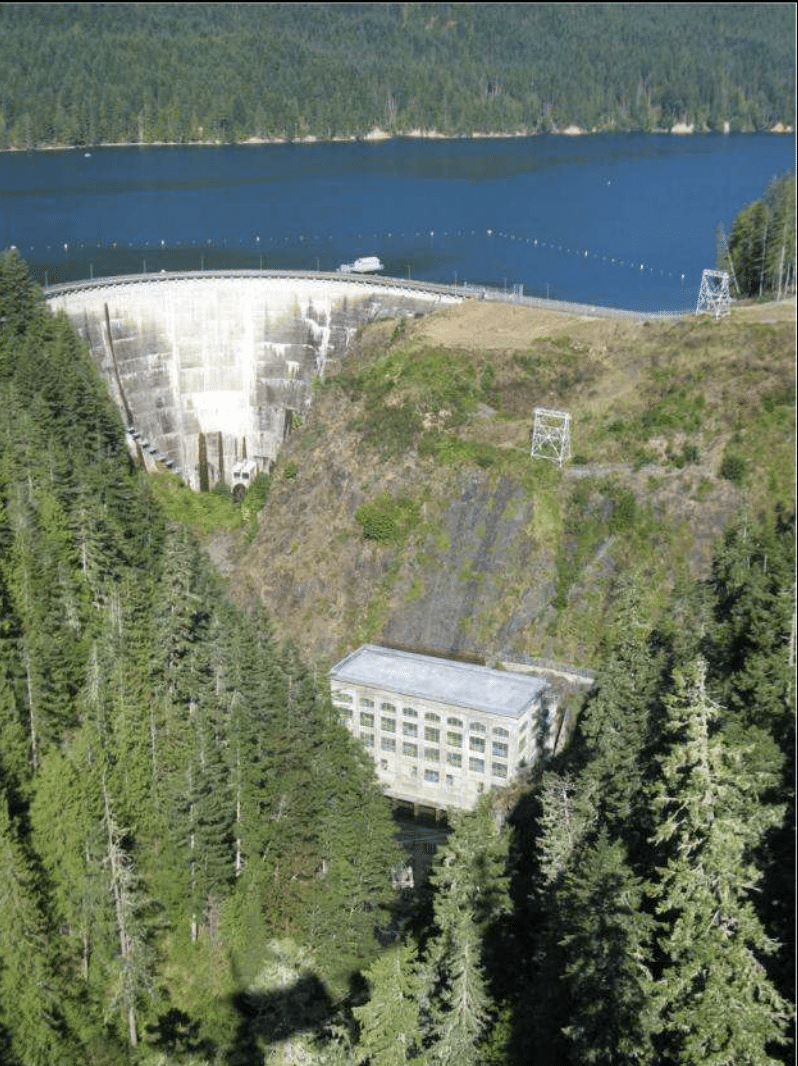

The Cushman dams, though not the game changers of the past, were engineering marvels in the 1920s. Hydroelectric projects like Cushman often were built in the mountains where deep ravines provide more height and storage potential, said TPU’s Wilson.

The amount of energy that can be produced by a hydro project is determined by the flow of water from snowpack and the volume of water stored behind a dam, which creates pressure. Multiple dams are often built in a cascading series on a single river to allow them all to generate power from a large storage reservoir at the top. The reservoir and snowpack function as a big battery, Wilson said.

That was nearly 100 years ago

Cushman Dam No. 1, which began generating in 1926, is 1,111 feet long and 275 feet high. It created Lake Cushman, which is 9.6 miles long and has 23 miles of shoreline. Dam No. 2 was built 2 miles downriver and began operating in 1930. It’s 575 feet long and 235 feet high. Its reservoir, Lake Kokanee, is 2 miles long and has 45 miles of shoreline.

There are two turbine generators at Dam No. 1. After water passes through them, if flows downriver and is stored in Lake Kokanee.

Water from Dam No. 2 goes two places. Some is released through two much smaller generators at the base of the dam into the river to provide fish and wildlife habitat. Much of the water is diverted through pipes down the mountain to Powerhouse No. 2 along Highway 101 near Hoodsport. This diversion provides for a much greater height — and pressure — before the water reaches the three generators and can therefore provide more energy, Wilson said.