Business Environment

Proposed Burley Lagoon geoduck farm upsets neighbors

For many residents, Burley Lagoon has long seemed the perfect Puget Sound backwater. It’s a working waterfront: Shellfish farming began there nearly a century ago, and has continued in a low-key way. The aquaculture blended in, adding colorful details like aged barges piled high with oysters to the tableau of abundant great blue herons, returning salmon and endless tidal mudflats.

Taylor Shellfish wants to switch from farming Manila clams and oysters in Burley Lagoon to geoducks. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

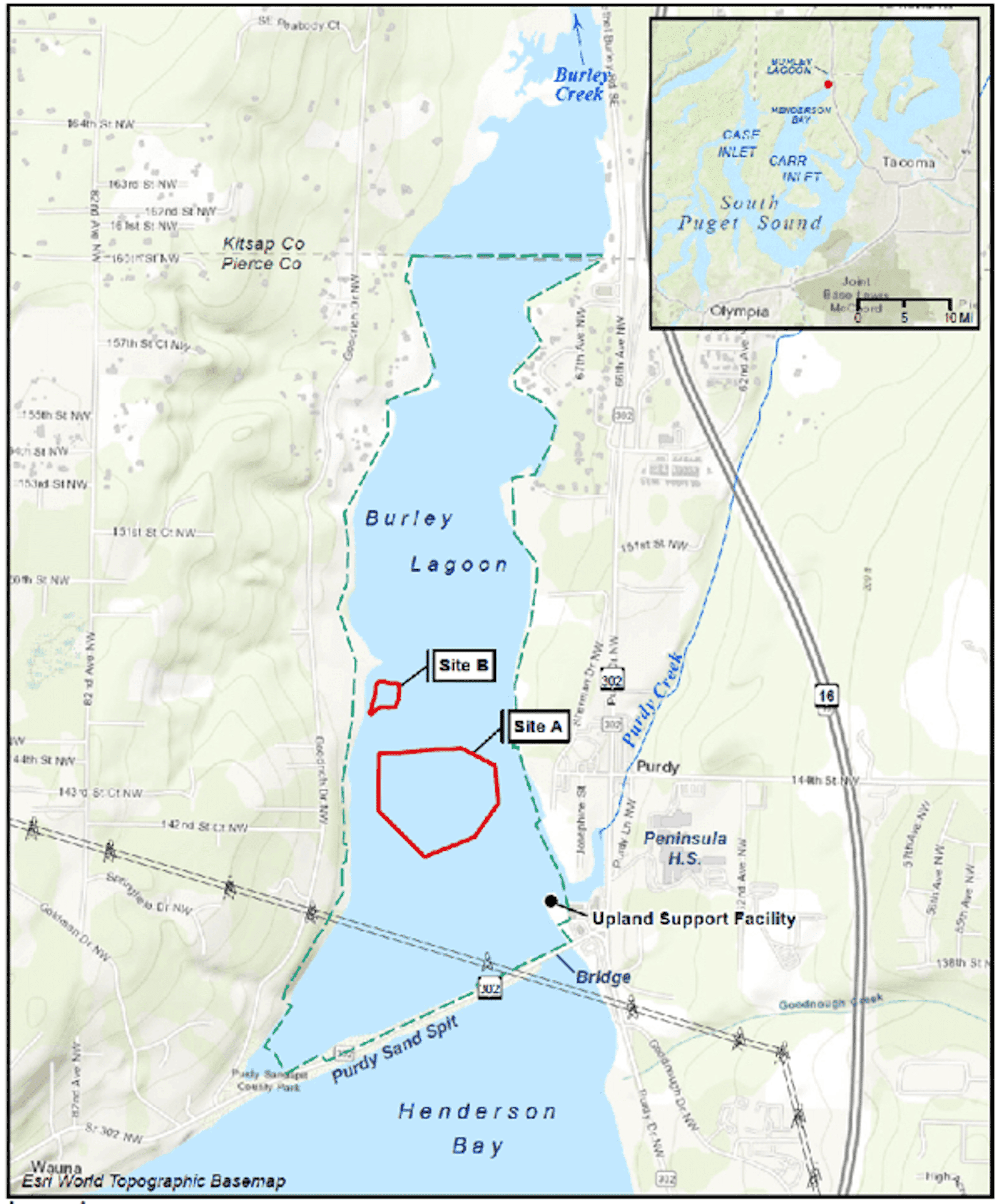

But these days, the romance of shellfish aquaculture has dimmed considerably for many locals. They are girding for a fight over what they view as a estuary-transforming proposal by Shelton-based Taylor Shellfish to convert 25.5 acres in the heart of Burley Lagoon, now used for growing oysters and Manila clams, into the largest geoduck clam farm in Pierce County, and possibly the south Sound. While Panopea generosa, bursting from its shell with a ridiculously long siphon, may serve as a Northwest icon, the commercial operations raising the massive mollusks have become anathema to lovers of pristine beaches, pitting shoreline dwellers and environmentalists against shellfish growers (often Taylor Shellfish) in battles that have erupted around the southern Salish Sea.

The most visible — and hated, by opponents — element of geoduck farms is their grids of “nursery tubes” usually made of PVC pipe to protect young clams. These jut several inches out of the mud at intervals of 1 to 1.5 feet, or up to 43,560 tubes per acre, during the first two years of the geoducks’ 6-year growing cycle. Also objected to are the mesh “predator exclusion nets” draped over the shellfish beds, and the geoduck harvesting method using pressurized water that liquefies surrounding mud so that the giant clams can be plucked out.

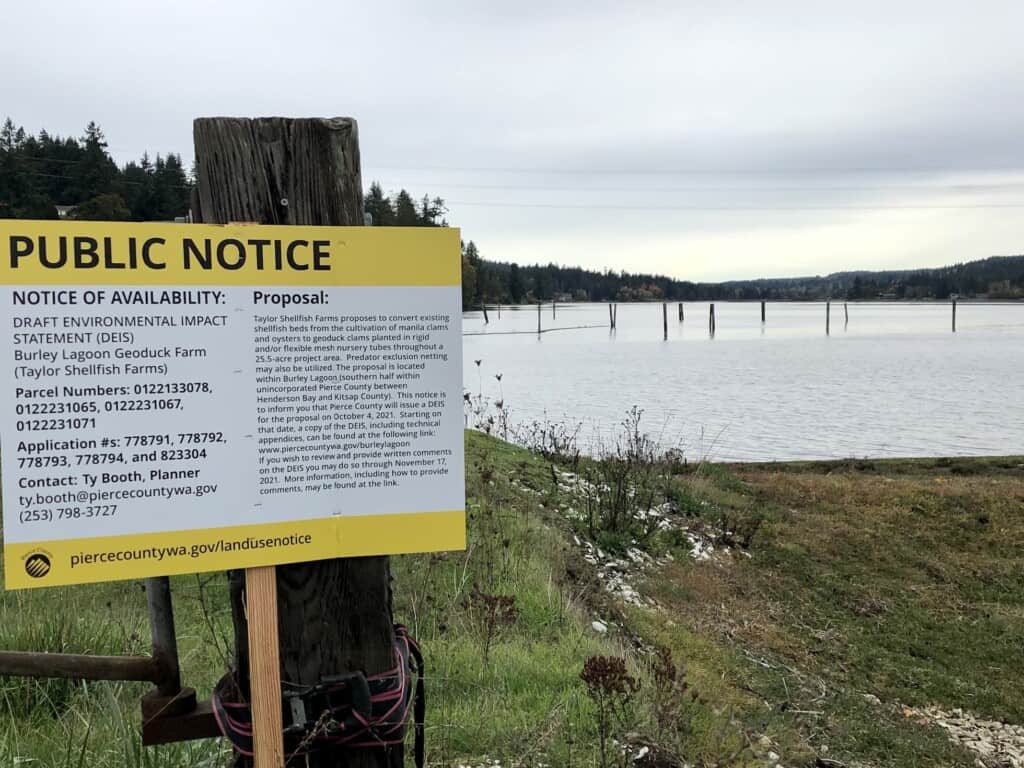

A key moment in Taylor Shellfish’s drive to gain permits for the massive Burley Lagoon geoduck farm, and local residents’ efforts to stop it, arrived earlier this month. On Oct. 4, the Pierce County Planning and Public Works Department released a draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) outlining the proposed farm’s likely biological, ecological and aesthetic effects on the surrounding area. That opened the process to community input. While insiders view a final decision as unlikely before 2024, the DEIS release takes the issue out of planning offices and into the realm of hearings, public testimony and appeals that will likely recur over the next few years as regularly as the tide floods and ebbs in Burley Lagoon.

Specifically, the draft EIS solicits comments for county planners to incorporate into a final EIS. That document, in turn, becomes grist for the local Gig Harbor and Key Peninsula land use advisory commissions (both are involved because the affected area straddles their boundary), which will hold hearings with opportunities for public comment before sending their staff reports and minutes to the Pierce County hearing examiner.

The hearing examiner will hold a hearing on permits for the geoduck farm and invite public testimony. Based on hearing findings, the final EIS and the input from the two local planning commissions, the hearing examiner will make a recommendation to approve or deny the permits, kicking the decision upstairs to the state Department of Ecology, which will consider the requested permits and rule in-house whether to issue them.

End of story? Not quite. Any party dissatisfied with the Department of Ecology’s decision can appeal to the Washington Shorelines Hearings Board. That opens up a new appeals process at the state level.

But while the end of the process is far off, opponents of the proposed geoduck farm are eager to have their say — if perhaps a bit intimidated by the highly detailed, 248-page report.

“We are meeting in little groups that are working on our comments in response to the DEIS,” said Karen McDonell, who has lived for 41 years on Burley Lagoon’s east shore. “All we can do is state our case.”

The report, early on, suggests that in fighting the proposed geoduck farm on biological or ecological grounds, opponents will have their work cut out for them.

“The Burley Lagoon Geoduck Farm Biological Resources Technical Report found that conversion of the type of shellfish culture on the 25.5-acre site from clam and oyster to geoduck would not represent a significant change in terms of effects on biological resources or ecological functions compared to existing aquaculture operations (Confluence Environmental 2020),” it reads.

With the window for testimony and written comments opening, opponents hope to refute the experts relied upon in the DEIS. Longtime resident McDonell echoes others when she responds that much of the science in the report is industry-generated.

“Tobacco science should never be forgotten,” she said.

Taylor Shellfish Farms is proposing to raise geoducks like these in Burley Lagoon. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons/Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

The acrimony of the permitting battle is a far cry from Burley Lagoon’s tranquility in preceding decades. Its tidelands became privately owned under late 19th Century legislation promoting oyster farming. Following on the colorfully named Tyee Oyster Co. and Whiz Fish Products Co., companies owned by the Yamashita family acquired the tidelands in 1952 and farmed the 300-acre tract until leasing it all to Taylor Shellfish in 2012.

The lagoon became popular as a residential area after aquaculture was established — the shellfish industry can rightly claim it was there first. But for many years, Burley Lagoon’s aquaculturists and waterfront residents struck a balance.

“At night, listening to the farmers, it was kind of sweet and romantic. You could hear them walk on the beach and they would pick up the oysters and toss them onto a barge,” McDonnell said. In the morning, with the tide in, a skiff would appear to tow the barge away as gulls circled overhead.

But when Taylor took over, shellfish farming in Burley Lagoon intensified, using new methods and materials, its neighbors said. Taylor scraped the lagoon bottom in places, removing species such as snails and starfish, residents say.

“I haven’t seen a crab there in years” and there are no longer birds on her beach, said Heather McFarlane, an east shore resident and president of Friends of Burley Lagoon, a group opposing the geoduck farm.

Taylor also introduced or increased the use of netting spread across shellfish beds, McFarlane said. During recent algae blooms, algae dried onto the nets, warming the tideland and shellfish underneath and fostering bacteria that released a stinking sulferous odor, residents said.

The company introduced or greatly increased the use of gear such as plastic mesh oyster bags and metal crates, residents said, which break free and wind up on local beaches.

Shoreline resident Carl Marlow, in front of his house, shows some of the aquaculture debris he has cleaned from the lagoon. Ted Kenney/Gig Harbor Now

“It is not being maintained,” said Carl Marlow, a west shore resident.

Taylor Shellfish declined to comment on residents’ complaints about its current farming practices in Burley Lagoon, preferring to focus instead on the EIS process.

That document does contain details that may assuage some residents’ concerns, depending on their expectations. For example, addressing concerns over the proposed farm’s visual effects, it notes that only 7.9 acres of the geoduck culture area would be exposed at an average low tide, with geoduck nursery gear visible up to approximately 28% to 30% of daylight hours in late spring and summer (i.e., between May and August), and for less than 3.2% of daytime hours between November and January.

Asked what Taylor Shellfish will gain by converting 25.5 acres of Manila clams and oysters over to geoduck cultivation, Bill Dewey, public affairs director, said, “Overall, the advantage to adding geoducks to our portfolio is just diversification.” A particular product line can collapse, or might fall victim to disease. Growing diverse species can lessen that risk.

Adding geoduck aquaculture in Burley Lagoon will also create jobs, Dewey said. If Taylor Shellfish gets permission for the entire 25.5-acre farm, it will employ an additional 8 to 12 workers there; a scaled-down proposal considered in the DEIS, with only 17 acres in active cultivation, would add six to 10 jobs, Dewey said.

Another benefit of the proposed Burley Lagoon geoduck farm would be the clams themselves, for those who like to eat them. Most would-be diners are in China and other Asian countries, to which the vast majority of Washington’s geoduck crop is exported. Farmed geoduck brings a premium price on the Asian market because it is “smaller, whiter and cleaner” than geoduck that grows wild in Puget Sound, said George Palmerton, owner of Citriodora USA, a Poulsbo-based seafood exporter.

And 2021 is shaping up to be a good year for the geoduck industry. The state’s exports of live, fresh clams and cockles — a category dominated by geoducks — topped $54.7 million in total value through August of this year, an increase of almost 43 percent, according to the Washington Department of Agriculture. After taking a battering in recent years from forces ranging from Chinese tariffs to greatly reduced air freight availability due to COVID, the industry is hoping for bumper crops and higher prices in the years ahead.