Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Early vehicles really cranked up the injuries

Gig Harbor Now and Then’s last question of local history concerned a list of injuries, mostly broken or dislocated bones in the arm or wrist, from the 1920s to the 1940s. The three big clues given were that the accidents happened to far more men than women, were not seasonal and most often happened just when you were about to go someplace.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

What accident, happening during what activity, caused all those injuries?

Answer: The backfiring of a gasoline engine while being cranked by hand to start it.

Ed Friedrich, Tomi Kent Smith, and Paul Spadoni all posted the correct answer on the Gig Harbor Now Facebook page.

Coming from a guy with a unique skill in putting out antique gasoline engine fires, it’s no surprise that Ed had the right answer. And I swear I didn’t give Paul any more clues than were published in the previous column, in spite of the two servings of strawberry shortcake his wife gave me.

This beautifully restored Model T Ford, complete with a hand crank for starting, belongs to Paul Michaels of Glencove. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Before the invention of electric starters, there were only two ways to start a car or tractor: By coasting the vehicle, or by turning the engine by hand using a steel crank.

The crank handles of Model T Fords probably broke more bones than any other make of car, truck, or tractor, simply because the Model T was produced in higher numbers than any other crank-started engine in history. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Cranking by hand was most often employed, only because it was usually the most practical method. With stationary engines, it was the only method. But hand cranking an engine was not always a benign task.

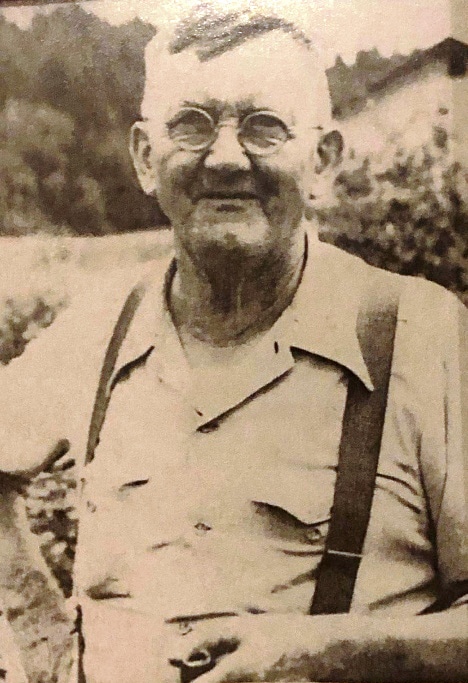

In 1931, Sivert Swenson of Purdy, the road supervisor for the local stretch of state highway, broke his right wrist while crank starting a Fordson tractor. Photo provided by his great-great-grandson, Joe Steiner.

Hand-crank starting didn’t have to be dangerous

There was a relatively safe method of cranking an engine, but all too often it was ignored. The proper way to turn a crank on most engines (depending upon the direction of rotation) was with the left hand, pulling up, and by cupping the handle with the fingers only. The thumb was not wrapped around the handle. That way, if the engine backfired, the handle was pulled from the fingers at the same time the momentum of the left arm pulled the hand away from the swinging crank.

But because most people are right-handed, too many people would make the potentially painful mistake of cranking an engine with the right hand. In that situation, if the engine backfired during the cranking, the crank could easily be (and often was) either violently pounded against the palm or fingers, or jerked completely out of the grasp of the cranker.

In the latter case, it would spin around in a circle so fast in the opposite direction that before the cranker’s arm could be pulled out of the way, it was often hit with such force by the crank handle that bones were sometimes broken or dislocated. And if you had a very strong a grip, the power of the backfire could dislocate thumbs and break bones even if you didn’t let go.

In the blink of an eye you could become bruised, battered, or broken.

Like other types of dangerous weapons, engine cranks were often holstered when not being used to maim or cripple. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Because hand-crank starting normally involved only a half turn or less, the crank wasn’t turned continuously around and around and around. Just a short burst of a single upward pull was all that was used. If the engine was very cold, flooded, worn out, or in serious need of a tune-up, that same short burst was repeated many times. In such cases, if the wrong method of turning the crank was employed, the odds of being punished by the crank handle increased proportionately.

In this 35-second YouTube video, the man turns the crank on a Model T Ford with his right hand, only when priming the engine. After he turns on the ignition switch, he pulls the crank up with his left hand to start it.

In this 12-second video, the same man shows how his left hand slipped free and out of danger when the engine backfired. Twice.

Electric starters were a luxury at first

In the first few years after the invention of the electric starter, only expensive cars had them. When they were first offered on tractors and less expensive cars, they were often only an option, rather than standard equipment. It took a long time for all cars and tractors to have electric starters. Until then, hand cranks continued to break bones, dislocate joints, clobber knees and strain backs. The injuries were so commonplace that only a very few were ever mentioned in the local newspaper.

In much the same fashion as automobile hand cranks could damage hands, wrists, and lower arms, motorcycle engines could cause similar injuries to the feet, ankles, and lower legs of riders using kickstarters. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Other accidents from crank starting

Sometimes crank starting injuries didn’t involve an engine backfire. Forgetting to put the transmission in neutral before cranking the engine could be even more dangerous. One good example was reported in the May 26, 1922, Bay-Island News, although the newspaper did a poor job in assigning blame:

“A Ford is able—and liable—to do anything. When Mr. Kavanaugh, our telephone lineman, cranked his Lizzie on the street Wednesday, Lizzie gave one snort and started off without the driver; the driver of the Matthaei bread wagon was busy digging bread from the rear of his wagon, when Lizzie picked him as her objective and attempted to braze him onto his own wagon. Though painfully bruised and pinched, the bread man travelled his route and returned to Tacoma on the one o’clock ferry. Frank Sweeney suggests that “Red” was trying to eliminate competition for his Irish friend who drives the opposition wagon!”

Early roads

Starting cars was not the only dangerous aspect to car ownership a hundred years ago. Driving on very poor roads was another frequent hazard.

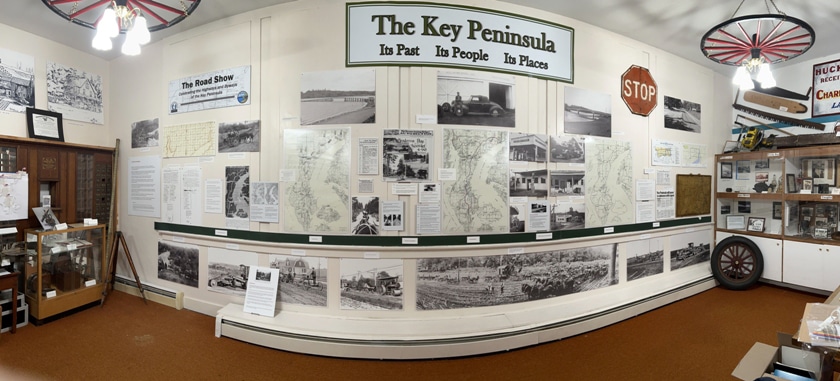

The evolution of local roads is the featured exhibit for 2024 at the Key Peninsula Historical Society Museum at the Key Peninsula Civic Center in Vaughn. Titled The Road Show, the exhibit explains how and why the first roads on the Peninsula were established, and how they evolved into the vital transportation arteries we use today.

The Road Show exhibit takes up an entire wall of the Key Peninsula Historical Society Museum in Vaughn. (The panorama function of the camera makes the wall appear curved in this photo, but it is flat.) Photo by Joseph Pentheroudakis.

The Key Peninsula Historical Society Museum is open from 1 to 4 on Tuesday and Saturday afternoons. Admission is free, although donations are greatly appreciated.

The Road Show at the Key Peninsula Historical Society Museum is well worth seeing in spite of the stain of the last name added to the Thank You list.

A companion piece to the early roads exhibit is Key Peninsula Road Stories, by Joseph Pentheroudakis, right here.

It gives short histories of several individual roads on the Key Peninsula.

Exposing a coverup

Many communities along the shores of the Peninsula were served by passenger steamers for decades before motorcars became a popular mode of transportation. When the age of the automobile dawned, it became evident that a means of transporting cars across Puget Sound was needed. While a few passenger boats could handle carrying a car or two on their decks as cargo, a real need for auto ferries which could handle drive-on, drive-off service developed.

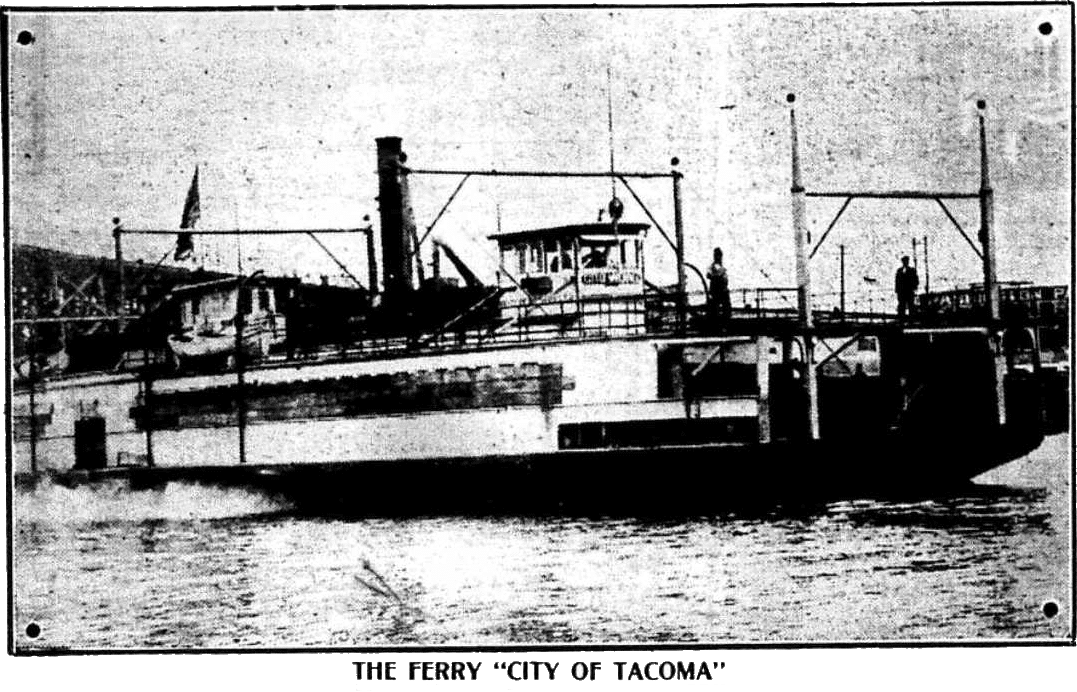

In 1919, Gig Harbor finally saw regular ferry service to Tacoma begin. Pierce County had purchased the side-wheeler ferry City of Vancouver from the city of Vancouver, Washington, in 1917. But for a reason that was ridiculous and embarrassing, it wasn’t put on its intended run to Gig Harbor until 1919.

After only a short time on the route, it became obvious that the ferry boat needed a roof over the car deck. It was pulled out of service for a short time in the summer of 1919 while a roof was installed at the Skansie shipyard in Gig Harbor.

Why did the ferry City of Tacoma need a roof over its car deck?

Sea gulls are a frequent sight on and around Puget Sound ferries. Photo by Greg Spadoni

What was the ridiculous and embarrassing reason Pierce County’s first auto ferry wasn’t put on the Gig Harbor–Tacoma run until two years after it was purchased for that purpose?

The ferry City of Tacoma did come to Gig Harbor from time to time during the two years it wasn’t carrying automobiles.

Why did the ferry City of Tacoma, purchased specifically to move automobiles between Gig Harbor and Tacoma, come to Gig Harbor during the two years it wasn’t carrying cars?

We’ll have the answers on March 25. And unless the editor balks at the idea, we just might also have the first Gig Harbor Now and Then Editorial Opinion.

Will it be worth waiting for? No. But that’s not going to stop publication. Only the editor can do that. We figure he’s unlikely to quash the piece if he strongly agrees with it, and that’s what we’re counting on.

As a matter of fact, it’s difficult to imagine anyone not strongly agreeing with it, which makes it seem strange that no one has ever broached the subject before. Whatever the reason for it, we’ll be aiming to break the complacency.

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.