Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | How the story of the Donkey Creek Bridge took a sharp turn

Our previous column told part of the story of the accident-prone wooden bridge across Donkey Creek in Gig Harbor from 1920 to 1949. Today’s column will tell the rest of the tale, including what the frequently mentioned sharp curve had to do with so many accidents on the old bridge.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

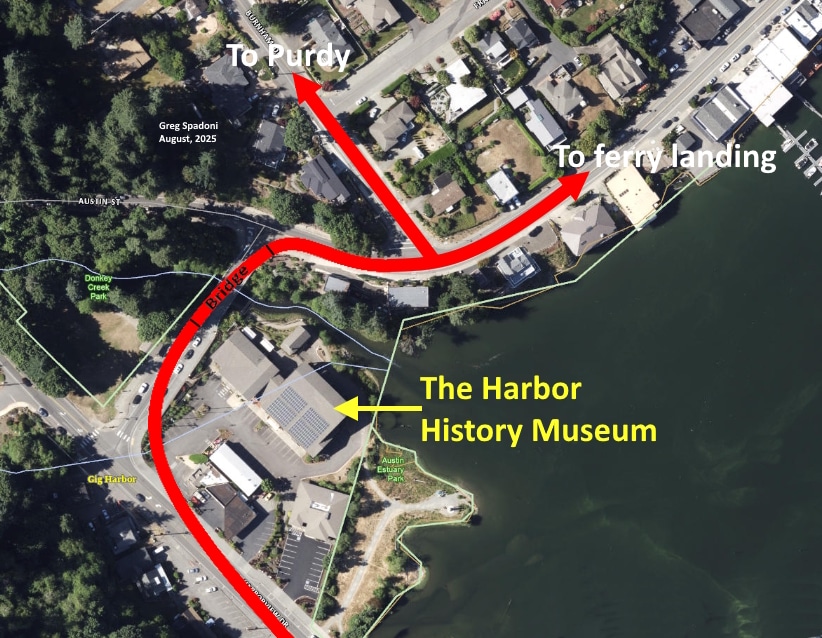

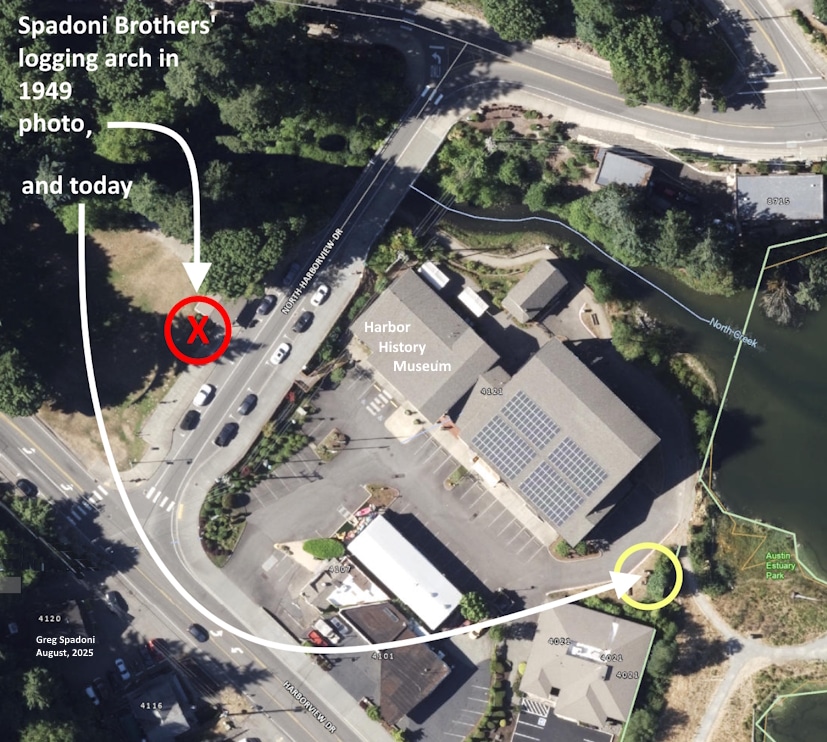

To review, there were many accidents at the old bridge crossing the then-unnamed Donkey Creek at the northwest corner of Gig Harbor. Too many cars were driving off the side of the bridge and landing in the water or mud below. A “sharp curve” was often mentioned as a contributing cause. The map below shows (in red) an overlay of the road leading to and from the wooden bridge on top of a contemporary aerial photo. Notice the curves at both ends of the bridge, now and then:

Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The curves approaching each end of the bridge were no sharper, and in fact a little less so, than they are today. That sets up the first question:

Why were so many cars driving off the side of the unnamed bridge at North Gig Harbor before 1935?

The second question is:

What was done in 1935 to reduce the number of accidents on the unnamed bridge at North Gig Harbor?

The clue that finally pulled both answers out of the fog of poorly documented history was in this clip, from the July 27, 1934, Peninsula Gateway:

“The long needed improvement which will eliminate the bad curve at the Austin Mill bridge, for through traffic from Bremerton is about to get under way. State engineers are now making arrangements for rights of ways and lines for the new road are being run. We understand that the cut-off will begin at the Leo Paradise [Paradis] property and run through the Hughes, Smith, and Novack [Novak] properties.”

“For through traffic from Bremerton.” That’s the key to this mystery.

The problem wasn’t the curve approaching the bridge from the west, or the curve from the east. It was the curve from the north that was causing a majority of accidents on the bridge.

When the road from the Peoples Dock at the foot of today’s Soundview Drive to the north end ferry dock near the foot of today’s Peacock Hill Avenue was paved in 1920, the route to Bremerton (via Purdy) was Burnham Drive, an unpaved road. A new county road to Purdy was to be built in 1920 or ’21, but was held up by litigation brought by disgruntled county taxpayers. When it was finally constructed, it was done not by the county, but by the state, as part of a state highway from Tacoma to Bremerton. The year it was finally built has escaped research so far, but was probably around 1922. One of the purposes of the new route was to avoid the steep, unpaved hill at the foot of Burnham Drive.

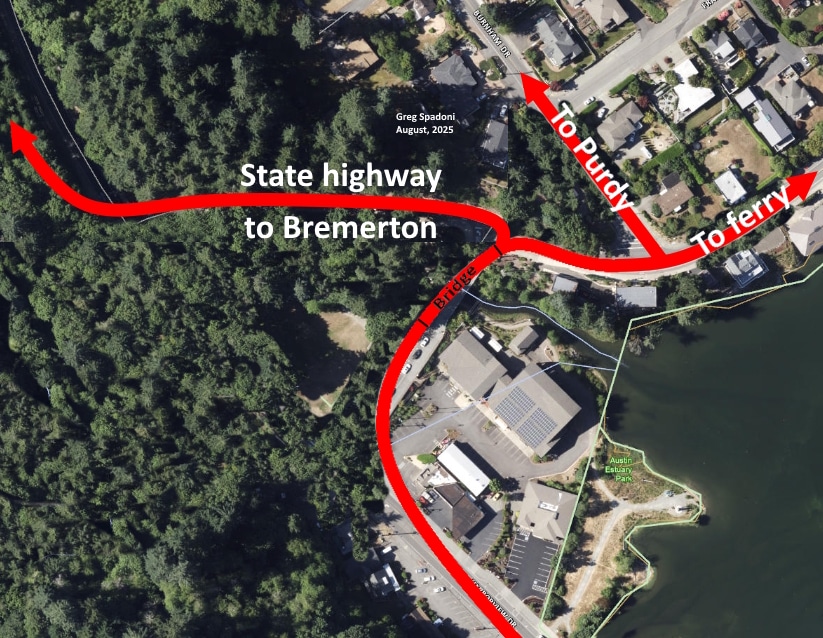

Beginning in 1923, when the ferry landing was moved from the north end of the bay to the dock beside today’s Tides Tavern, at the foot of Sounddview Drive, the state highway between Tacoma and Bremerton ran through the west side business district of Gig Harbor, across the wooden bridge over Donkey Creek, and turned left immediately at the east end of the bridge, continuing north on what is today Austin Street. The stretch of road that today passes by the city’s sewer treatment plant did not yet exist.

The state-built highway to Bremerton, through Purdy, bypassed the steep hill at the bottom of Burnham Drive. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Coming from the north, it would be dangerous enough to encounter a sharp 90-degree turn on the highway, but the right-hand curve onto the bridge was far more than 90 degrees. It was actually about 125 degrees. Drivers not expecting such a sharp turn would sometimes end up crashing through the south railing of the bridge, and some of those cars fell completely off, landing in the water or mud below, depending on the level of the tide.

It was the extra-sharp right-hand turn onto the east end of the bridge from the north that caused the majority of accidents on the old wooden bridge. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

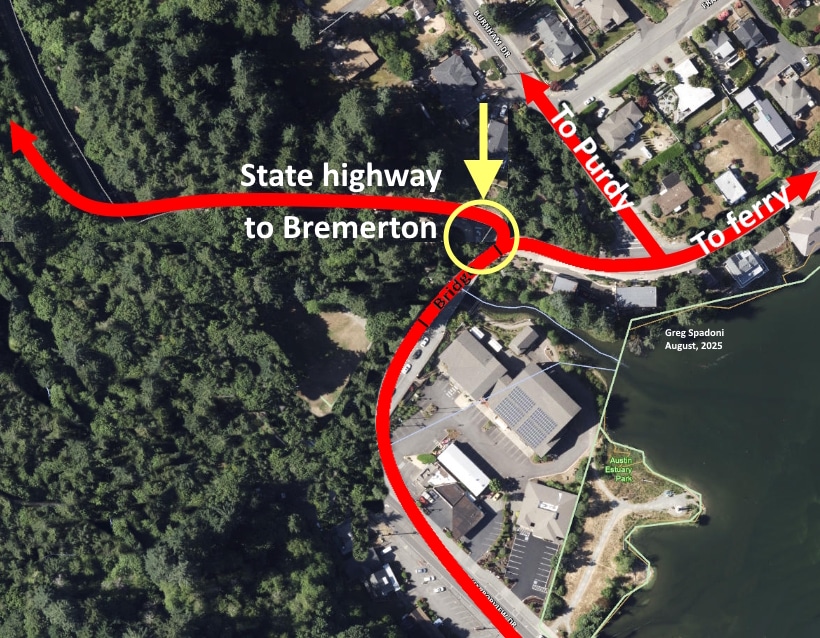

To fix that 125-degree accident nursery, the state highway department made the overdue decision to bypass the bridge. To do that, it acquired the right-of way for a straight stretch that was also a shortcut. The new piece of road was built in 1935, with the material cut from the hillside on the north side of the creek used to fill the low spot on the south side. The culvert under that fill was the first of two street-related obstacles reducing the natural flow of migrating salmon up Donkey Creek. The second obstacle was 14 years away.

In 1935, the wooden bridge over Donkey Creek was bypassed with a new, shorter route. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The source of the fill that made up the bridge bypass was the hill immediately north of where Austin Street intersects Harborview Drive today. The cut through the hill was somewhere around 300 or so feet long, and about 47 feet at its deepest point. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The origin of Austin Street

The key clue, “for through traffic from Bremerton,” also answers the unasked question, “What was the original purpose of Austin Street?” From 1935, when the state highway’s Donkey Creek Bridge bypass was opened, until 2013, when the current concrete bridge was built, Austin Street was very seldom traveled by any traffic. Only an occasional car, truck, or bus used it. Its very existence was puzzling to anyone unfamiliar with it having originally been part of the state highway system.

Austin Street was so seldom used that in the 1990s, during one of the expansions of the city’s sewage treatment plant, it was closed to traffic for months, if not a year or more. It was used as a temporary storage lot for excess dirt excavated for a new addition to the plant. Some of the dirt was used for backfill of the new construction at the treatment plant, and the rest was hauled off to other locations. I recall spending a day there myself with one of Spadoni Brothers’ rubber-tired loaders, loading out dump trucks.

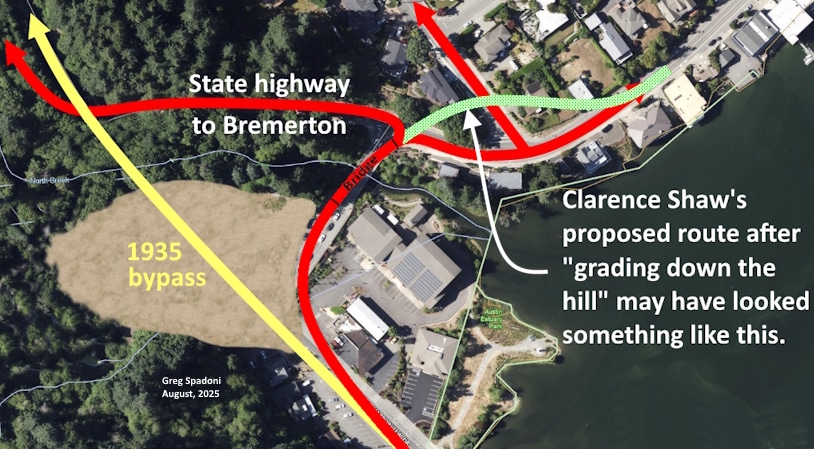

The original route of the state highway immediately north of the bridge over Donkey Creek went around the hill that was cut down in 1935 during construction of the bridge bypass. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Same bridge, more accidents

The rerouting of the state highway drastically reduced the number of accidents on the old wooden bridge over Donkey Creek, but did not eliminate them. The bridge itself had been partially rebuilt in 1937, but the approaches remained the same. With the nearly hairpin turn rarely used anymore, the double curve on the east end of the bridge started taking the blame.

Although the Peninsula Light Co. moved into the Hunt music store building, right next to the bridge, in 1930, The Peninsula Gateway doesn’t appear to have begun using the Light Co. as a reference to the bridge location until sometime after the company bought the building in December 1934. Once that reference stuck, the old references faded away. Here are three such references from The Peninsula Gateway:

March 27, 1942: “Mrs. Geo. Gilbert, her daughter, Birdelle and Mrs. Tangen, narrowly escaped injuries when the Gilbert car, with Mrs. Gilbert at the wheel, skidded on the bridge by the Peninsula Light Co., and crashed across the walk and broke the railing. The bridge was covered with an early morning frost and, though the occupants were badly shaken, no one was injured and the car was only slightly damaged.”

(“Crashed across the walk” makes it sound like the bridge got the sidewalk The Peninsula Gateway called for in a 1925 editorial. Perhaps during the partial rebuild in 1937?)

October 26, 1945: Two high school students were severely injured “when the automobile in which they were riding got out of control on the bridge near the Peninsula Light Company’s office at Gig Harbor. The car struck the guard rail on the bridge, careened across the span to the left side and crashed through the railing, falling about 50 feet to the bottom of a gulch, landing upside down in the mud. The tide was out at the time of the accident.”

December 7, 1945: A letter by Clarence Shaw to the Pierce County commissioner representing Gig Harbor was reprinted in the newspaper. “One of the most hazardous death traps … on this Peninsula district is right here in Gig Harbor. The history of the county bridge on the highway crossing the creek in front of the Peninsula Light company’s office is one of continuous mishaps and accidents. …It is only through the grace of God that those who have plunged through the railings of this bridge and landed in the creek 20 feet below, are alive today. … Hardly 30 days pass that some part of the bridge or the railings to its approach are shattered by some driver.”

Shaw suggested the danger could “easily be eliminated by grading down the hill and making a straight-away across the creek to the state highway.”

Clarence Shaw proposed cutting down the hill on the east side of the bridge to give the road a straight shot to it. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The infirmities of age

In addition to having always been somewhat dangerous for inattentive drivers, by the mid-1940s the bridge was deteriorating with age. The 1937 partial rebuild had extended its life, but by 1946, it wasn’t expected to last too much longer. On Aug. 16, the Gateway reported that “Notices have been posted on the bridge near the Peninsula Light Co., stating that loads of more than three tons are unsafe.” While that may have been bad news for the bridge, at least Austin Street was a short and easy detour for trucks and busses.

One of the last car-off-bridge incidents happened in early December 1948. “Four … peninsula residents probably owe their lives to the mud which rims the harbor when the tide is out. An automobile … plunged 30 feet off a heavily frosted bridge at North Gig Harbor Thursday night and landed on its grillwork in the bay mud. … The car skidded through the bridge railing and fell 30 feet to the mud, landing on its nose.”

Varying heights

Despite it having been the same editor and the same bridge, The Peninsula Gateway’s estimation of the distance from the bridge deck to the creek bed fluctuated wildly. In 1933, it was 20 feet. In October 1945, it was 50 feet. Two months later it was back down to 20 feet. In 1948 it increased by half to 30 feet.

The actual height of the bridge deck over the creek at low tide was never 50 feet, or anything close to it. In reality, the distance was around 20 to 25 feet. Today’s concrete bridge is about 25 feet above the creek at low tide, very close to the same as the top of the fill it replaced. A couple of old photos in the collection of the Harbor History Museum appear to show that the fill was a few feet higher than the previous wooden bridge.

Spadoni Brothers stopped the carnage

The final fix for the accident-prone bridge was set in motion by the Gig Harbor Town Council on June 17, 1949, when it voted to hire a local company, Spadoni Bros., to remove the bridge for $874 (the next lowest bid was $1,336). The job included placing a concrete culvert in the creek bed, in preparation for a road fill to be made to replace the bridge.

The Harbor History Museum has an interesting set of photographs of Spadoni Brothers doing some of the work.

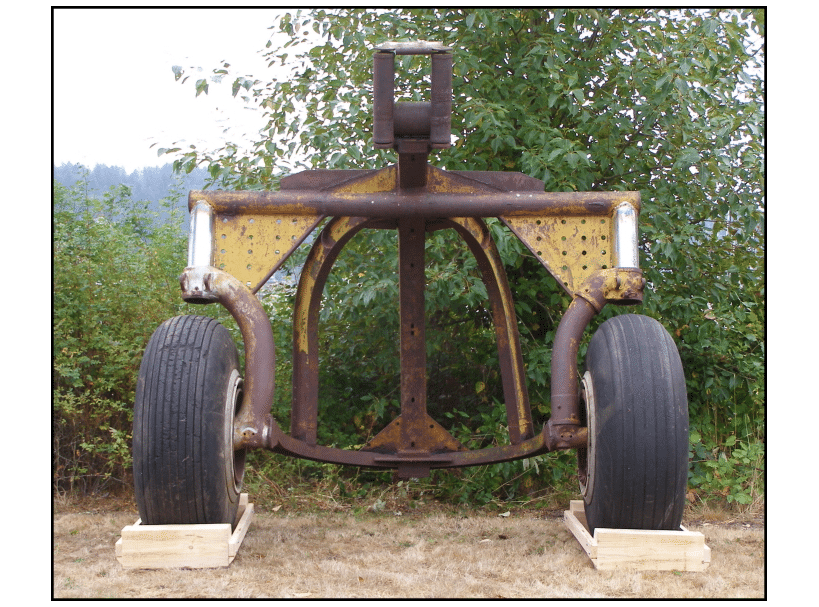

After taking down the bridge, the three brothers, Julius, Claude, and Rudy (Roy had not yet joined the company), were not sure how they were going to handle the heavy concrete culvert sections. As a fledgling road construction and logging company, they didn’t have a wide variety of machines to choose from. It was Claude Spadoni who came up with the idea to use their homebuilt logging arch. They regularly towed the arch with their International TD-9 bulldozer when dragging logs out of the woods, and Claude figured they could use it to carry, rather than drag, the culvert sections down to the creek. The concrete culvert pieces weighed less than some of the logs they yarded, and were very short by comparison, so their logging arch worked beautifully.

Claude Spadoni took time out from moving one of the concrete culvert sections down to the creek bed to take a photograph of the setup. Spadoni Brothers’ self-built logging arch behind their International TD-9 bulldozer did a fine job. (As an example of how long it could sometimes take to use an entire roll of film before having it developed, he took this picture in the summer of 1949, but didn’t have it developed until November, 1959.) Photo by Claude Spadoni.

This photo on the Harbor History Museum’s website shows just how good Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch worked for setting the culvert sections. The pipe is perfectly straight at a perfectly steady grade. (The hand-written date of 1950 on the upper margin of the photo is incorrect.)

In that same picture, if you look closely in the upper center, you can see the logging arch on the far side of the culvert, parked next to a utility pole.

Today, instead of looking closely for it, you can take a close look at it, as the very same logging arch is now a permanent exhibit outside the Harbor History Museum, at the southeast end of the building.

Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch is now on permanent display outside the Harbor History Museum. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The Clay Hill cut

Although the Spadoni Brothers removed the old bridge and set the concrete culvert in the creek bed, they did not place the fill.

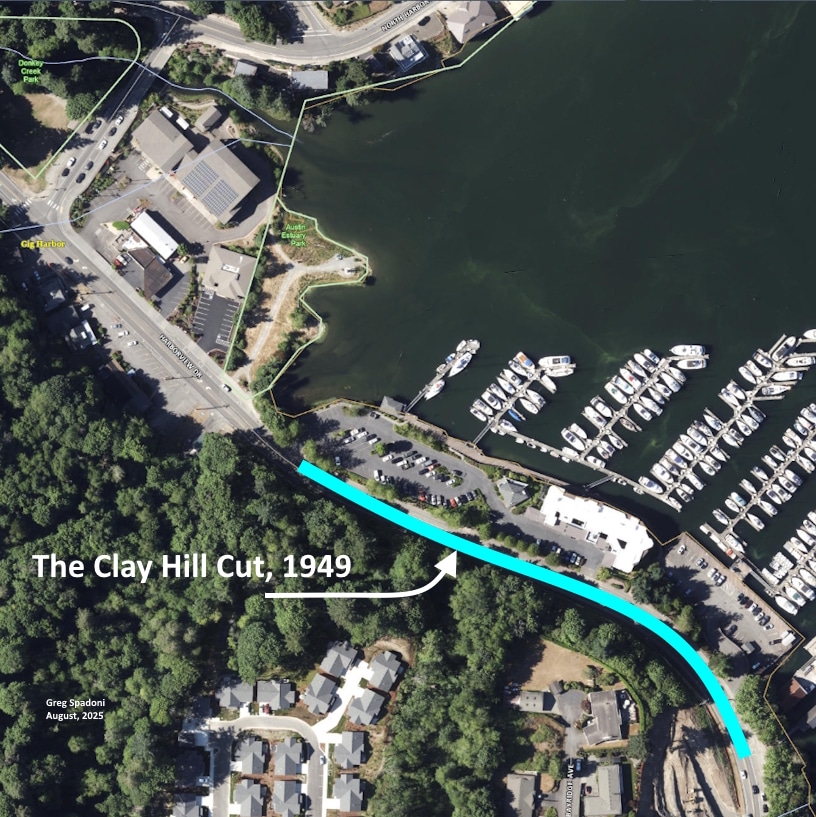

Shortly after they removed the old bridge and placed the culvert, Spadoni Brothers cleared a right-of-way over the tip of Clay Hill, just a few hundred feet from the newly placed culvert. A Seattle contractor then excavated for a new route of the state highway, further back from the beach, which became known as the Clay Hill Cut. It was the Seattle firm that hauled the dirt the short distance to the former bridge site and filled over the culvert.

Spadoni Bros. cleared for the Clay Hill Cut in the summer of 1949, but a Seattle company did the excavation. Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

The culvert replacing the bridge was the second obstacle to normal salmon migration in Donkey Creek. The first was the culvert under the shortcut road, placed in 1935.

In September, after the fill was placed and compacted, the town of Gig Harbor again hired Spadoni Brothers, this time to grade and gravel the new stretch of road, 40 feet wide. The estimate given to the town by Julius Spadoni was $200 for 200 cubic yards of gravel, and $6 per hour for the grading, not to exceed 12.5 hours.

For the next 64 years there was no bridge across Donkey Creek there.

Creating a gap to bridge

In certain situations over time, the recognition of unintended consequences increases and priorities change. More than 60 years after it had been placed, the city of Gig Harbor recognized the improvements, primarily to spawning fish, that would result from removing the 1949 fill and culvert from Donkey Creek. The project required a new bridge to be built, but with two key differences from the wooden span that the fill had replaced. The new bridge would be made of concrete, and would carry west-to-east traffic only.

The current bridge opened in 2013. The reduction of traffic to only one lane gave new vitality to Austin Street, which now carries all of the east-to-west traffic that used to flow across the fill that was removed. The unused traffic lane on Austin Street is now a line of parking spaces that is very popular with people who like to walk the Gig Harbor waterfront.

The lone survivor

As of this writing, the fill’s gone, the culvert’s gone, but the logging arch endures.

Donated by John Spadoni in 2022, Spadoni Brothers’ gracefully imposing logging machine has since been on display outside the Harbor History Museum. It’s not far from the mouth of the creek it was used to set the concrete culvert in during the summer of 1949.

Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch has been on display outside the Harbor History Museum since 2022. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

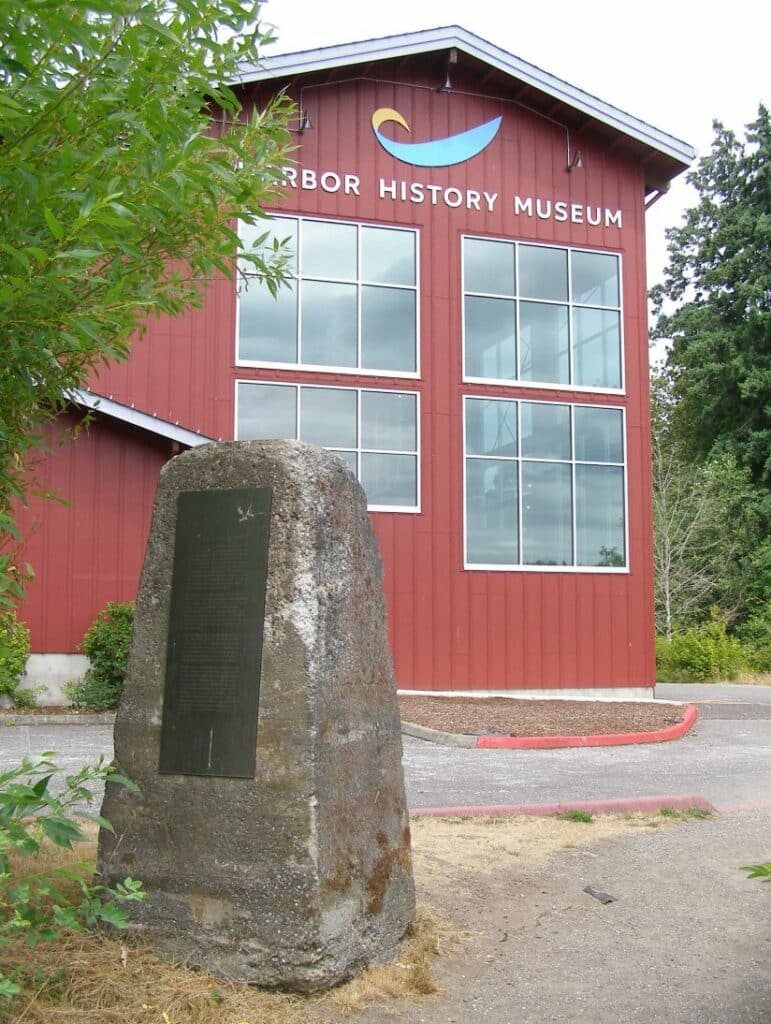

Within spitting distance (for some people; not me) of the Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch is a tapering, six-foot-tall, three-ton concrete pylon, one of five along the walking trail behind and beside the Harbor History Museum.

The concrete pylon, left, and the Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch, right, are within … well, let’s just say they’re not very far apart. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The five pylons and many others originally supported the 1920–1949 wooden bridge, and were buried in the road fill where they stood (or were knocked over) after the bridge was removed. When the fill was excavated to reopen the creek, the pylons were rediscovered.

Five of them were saved by the city of Gig Harbor’s Historic Preservationist Lita Dawn Stanton, who recognized their historical value. It was her idea to place them along the trail from Donkey Creek Park to Austin Park. They are a permanent reminder of the last wooden bridge across Donkey Creek, which leads to the story of the concrete culvert, the road fill, and the ultimate restoration of the creek bed. They also serve to hold stainless steel placards that tell the story of the land on which they stand.

Each of the five salvaged bridge support pylons now display a stainless-steel plaque that tells part of the history of the land upon which they stand. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Next time

It should be obvious that Spadoni Brothers’ logging arch needs to be featured in a future Gig Harbor Now and Then column, and it will be. But it’s not the subject of the next one. It would’ve been, if not for something more timely having come up, the story of death and burial in the early days of the Peninsula. It’s more timely because of the announcement of guided tours to be given at the Artondale Cemetery next month. It seemed like a good idea at the time to tie into the cemetery tours with a column on dead pioneers, and it still does, so that’s the plan.

If you’d like to take one of the four tours of the Artondale Cemetery — two on Sunday, Oct. 12, and two on Sunday, Oct. 19 — you can buy your tickets here.

This is a prime opportunity to not only hear interesting stories about people who are long gone, but to do so with a small group of other like-minded people. With their inability to respond, it’s kind of like talking about the dead behind their backs, except they’re all buried face up. But they are buried, which means if something were to be said not to their liking, there’s no danger of reprisals. On the off chance they did hear something they didn’t like, they’re not going to give you the stink eye. And even if they did, you wouldn’t know it.

The tour guides are not going to be talking trash about the residents anyway. They’ll be talking about the departed’s impressive accomplishments and empathizing with the hardships and tragedies previous generations had to endure. The whole point of the tours is to present interesting information.

That’s not to say there isn’t any frivolous, snippy, or serious gossip known about some of the long departed, because there is. But the tours are not the venue for that. This column sometimes is, though, so stay tuned for some of that from time to time. And one of those times will be next time.

In a two-part series beginning on Sept. 22, we will profile the deaths and burials of three pioneers from Rosedale and Gig Harbor, homesteaders all. Two of them are in cemeteries and two of them are lost. That may sound like four, but in this case two and two equals three. It’s all part of the mystery of the Great Beyond. Either that, or it’s a case of lousy record keeping on the part of a local cemetery not named Artondale.

(It’s lousy record keeping.)

— Greg Spadoni, September 8, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.