Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Little House in the Hayfield

Who among us has not wondered about the story behind the charming, old, empty farmhouse in a hayfield beside Point Fosdick Drive?

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

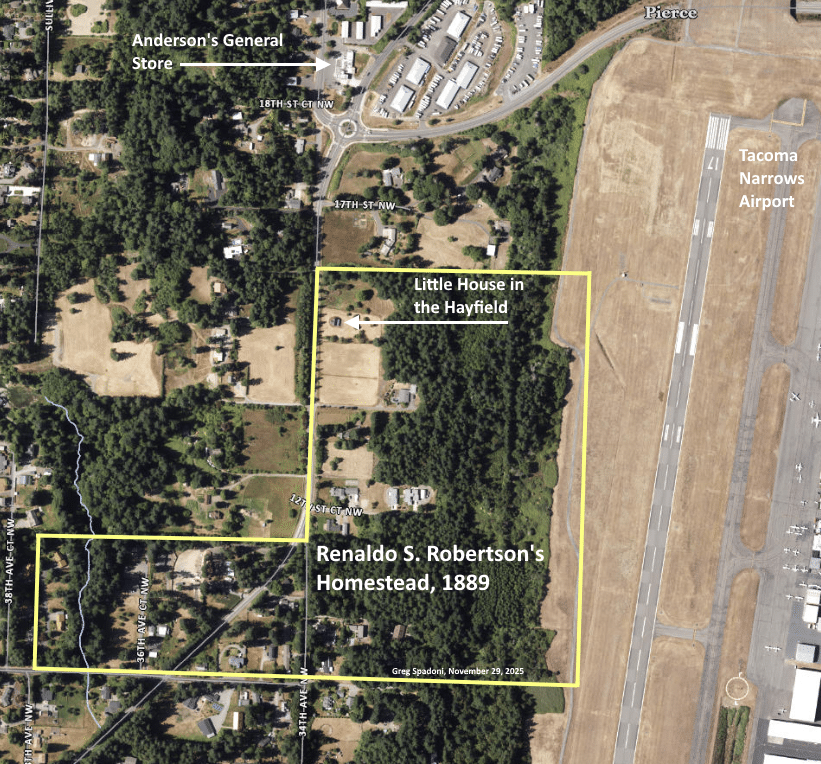

Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer aerial base map.

Those who’ve never seen it, that’s who.

But for anybody who has seen it, it’s a very good bet you’ve wondered what its story is. I have wondered that. Nobody seems to know. So, guess who had to look into it?

Photo by Greg Spadoni.

What kind of story would this house turn out to have, I wondered. A dull, boring one, or the kind that holds a reader’s interest?

It’s always good when a subject’s history turns out to be interesting, and this one sorta did. Not in a definitive, satisfying fashion, but in a just-the-facts kind of way.

It started out quite promising, with a little-known early local mover-and-shaker taking the lead, but that was a false trail. The real story is a lot more complicated.

1889

The first owner of the property acquired it through the Homestead Act of 1862. He was Renaldo Shaber Robertson, originally from Maine, having been born there in 1845 and married there in 1873. He filed a homestead claim on 80 acres of Point Fosdick on May 6, 1889.

It’s difficult to tell if he was married at the time of his homestead filing because reliable dates of the second of his four marriages and first divorce couldn’t be found. His first wife, Margarite Anna Collins, died in 1881, three years after their second son was born. Sometime after her death, he moved to Oregon, which may be where he married his second wife. It seems likely that he married his third wife on Christmas Eve 1892. She was Helen Easter, a widow, with a 15-year-old son, Phillip.

Renaldo (frequently spelled Rinaldo) Robertson’s time on the Peninsula was busy. He was primarily a subsistence farmer, but also found time to be the Wollochet postmaster (1892-94; the second of only three at Wollochet before it was absorbed by the Gig Harbor post office); marry Helen Easter; become a licensed school teacher (1898); and get elected Artondale Justice of the Peace (1902; the Point Fosdick area was part of the Artondale voting district at the time).

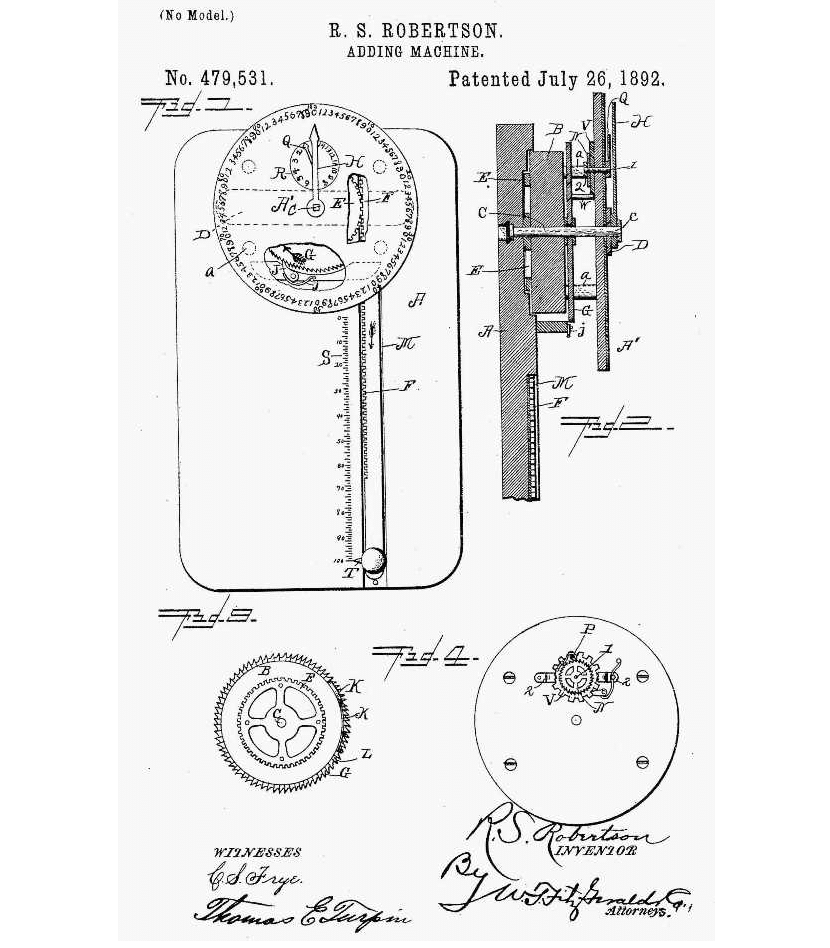

He also found enough spare time to be an inventor. His idea was for a mechanical adding machine. He submitted an application with the U.S. patent office in October 1891, and received a patent, number 479,531, less than a year later.

S. Robertson’s patent application begins: Be it known that I, RINALDO S. ROBERTSON, a citizen of the United States, residing at Artondale, in the county of Pierce and State of Washington, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Adding-Machines; and I do hereby declare the following to be a full, clear, and exact description of the invention, such as will enable others skilled in the art to which it appertains to make and use the same.

No evidence was found of his invention ever having been manufactured.

No cigar

As interesting as Renaldo Roberston was turning out to be, he’s not the one who built, or even lived in, the Little House in the Hayfield. The location of his house on the homestead is unknown, except that it wasn’t where the hayfield house is today.

In 1896, Robertson sold the 10 acres where the hayfield house would later be built. The sale wasn’t recorded until 1899, which begins the complications in following the trail of the house’s history.

The Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer Information Portal says the hayfield house was built in 1900. The Assessor’s dates of construction are often wildly inaccurate before about 1970, so it should be no surprise that 1900 is not the actual date.

A long chain of ownership

The Robertsons sold the 10-acre piece where the house was later built to Gerald G. Groves. Groves was a teacher, and later a principal, at a Tacoma school. He didn’t build the house, either.

He sold the 10 acres to Anton Brink in June 1905. At $240, there was no house on the 10 acres at the time, or at least not the house that is there today, which was a pretty nice home in its day. If there was any building on the property, it was nothing more than a small, cheap shack.

Brink made an impressive profit on the land when he sold it four months later to Christian Olsen for $375 in October 1905. For that price, the house in question still wasn’t there.

There is strong reason to believe Olsen built the house. If not him, then his son.

In 1908, Olsen sold the 10 acres to his son, Christian Hemstead, for the symbolic price of $1. Along with the property came a flawed spelling of Hemstead — Hemstad — on the deed. That spelling, along with Henestad and Hemsted, caused some problems in tracing the family, but didn’t stop progress.

Why Christian Olsen’s youngest son’s last name was Hemstead is a question for another time, but the connection is definite.

Christian and Anna Hemstead and their several small children lived on the property for about five years. The proof of the house having been there during their stay is the price they sold the property for: $1,825, to Gabriel Maartensen Evje in December 1913.

The Hemsteads had made it clear that they intended to move to Eastern Washington to farm wheat. They eventually did, but lived a bit longer at Wollochet on someone else’s property after selling the farm to Evje.

Gabriel Evje and his wife may not have lived in the hayfield house. They had several pieces of property in the area, one of which they were already living on, so it’s possible they bought the place as an investment.

A mean drunk

Long before he bought the Little House in the Hayfield, Gabriel Evje had established a reputation as a mean drunk. On October 23, 1905, The News Tribune told an interesting tale about him.

Under the headline, “POWERFUL RANCHER TAKEN INTO CUSTODY,” the story reads, “Gabriel M. Evje rancher living near Wollochet Bay, was found in Tacoma today and taken into custody … on complaint of neighbors of the man’s family who, it is said, he had driven from home Saturday night.

“He is a large, powerful man, about 50 years of age. He is said to have been acting in a dangerous manner for some time. He had consulted a doctor in Tacoma and had cautioned him to abstain from … the use of alcoholic stimulants.

“Contrary to this advice, it is said, he frequented Tacoma last week and had worked himself into a desperate physical and mental condition.

“He was found on K street today and taken to jail, where he told the officers a story of having much trouble with his daughter, who insisted in going to some other church.”

The Tacoma Daily Ledger added that Evje “was formally charged with being insane.”

When he sobered up the next morning, he was acting normally, leading the jailers to believe he was not insane. A lack of further reports suggests they let him go.

Gabriel Evje sold the house and 10 acres to Alexander Fleming Ogilvie and his wife, Eliza, in 1915 for $2,650.

Some kind of curse

There’s no reason to believe the Little House in the Hayfield is cursed, but the Ogilvies seem to have been.

Alex Ogilvie was a “master mariner,” according to his multiple listings in the Tacoma City Directory. He had moved to Point Fosdick to semi-retire, or so it looked. But World War I got in the way. He agreed to captain a new ship carrying supplies to Europe in 1918. The U.S.S. Westover was torpedoed by a German submarine, with multiple lives lost. Ogilvie was blamed.

From the website of the Naval History and Heritage Command:

The Court of Inquiry into the loss of the U.S.S. WESTOVER has completed its labors and come to a decision after sessions lasting seven days, 17 July – 23 July 1918.

The decision, which is a lengthy one, contains in summarized form the following items of special interest:

That the WESTOVER was sunk by the explosion of two torpedoes fired by an enemy submarine; that the eleven officers and men who died as the result of the accident lost their lives while in line of their duty and not as a result of their own misconduct; that Lieutenant Commander A. F. Ogilvie, U.S.N.R.F., Commanding the WESTOVER, failed to carry out his instructions to zigzag in clear weather, failed to keep the radio operators informed of the ship’s position at stated periods, as laid down in his instructions; that from the radio operator being in ignorance of the ship’s correct position effective rescue was prevented, resulting in the surviving members of the crew suffering injuries incident to five days exposure in open boats; that no officer or man is responsible for the loss of the ship nor for the consequent loss of life, etc., except the injuries incident to exposure in open boats, for which Lieutenant Commander Ogilvie is indirectly responsible in that he failed to keep the ship’s position posted in the radio room, resulting in an incorrect position being broadcasted and effective rescue prevented.

The court is of the opinion that Lieutenant Commander Ogilvie, U.S.N.R.F., committed a serious error in judgment in not zigzagging on the day that the WESTOVER was torpedoed, and in failing to keep the radio operators informed of the ship’s position, for which the court recommends that he be reprimanded.

The general court martial appointed to try Lieutenant Commander Alexander F. Ogilvie, U.S.N.R.F. for “Drunkenness” has finished its sessions 25 July 1918; and has sentenced him on his plea of “guilty” to be dismissed from the United States Naval Reserve Force. The court recommended clemency, but the convening authority approves the sentence.

Ogilvie’s loss of the ship and crewmembers weighed on him heavily. It was ruled the probable cause of his suicide by gunshot while helming a civilian ship loaded with flour from Tacoma to New York in July 1919. His body was buried at sea off the coast of Mexico. He was 54.

Eliza Ogilvie also had a tragic ending, just three months later. She died on Oct. 18 at age 45 of peritonitis from a perforated ulcer. She’s buried in the Artondale Cemetery.

More bad luck, but not tragic

The Ogilvie estate sold the house on 10 acres to Richard and Anna Angeline in December 1919 for $3,000. In turn, they sold it to Edward J. and Lou Doherty in September 1920, for $4,500, on a contract.

Richard Angeline and his wife might not have lived there, but the Dohertys definitely did. In fact, the women of Wollochet met there to work on their hats in May of 1922, according to the Tacoma Daily Ledger.

But the Dohertys apparently didn’t keep up with their payments, for the Angelines sued them and won. Not only did they get the property back, but according to the quitclaim deed signed by the Dohertys, the Angelines also received “One cow, One heifer, One pig, One horse, 2 wagons, and 24 chickens.”

The Dohertys learned not to mess with the Angelines.

A stable owner

The Angelines, who lived on the Tacoma side of the Narrows, probably rented the place out until they sold it in 1926 to Krist Wall. The deed states that the property sale also included “all tools, stock crops houses and improvements.”

The punctuation was lacking, but unless the place was trashed (which it must’ve been), Wall got a bargain at just $2,000.

Much like the Hemsteads, the deed seems to have butchered the buyer’s name. Instead of Krist Wall, his name appears to have been Chris Woll. The probability looks to be about 99%, which is not quite certain, but extremely likely.

Chris Woll was a commercial fisherman, with his boat, Sockeye, based in Seattle. If he is indeed the one who bought the Little House in the Hayfield in 1926, then he was the first owner to stay for many years. He died in 1963 at the age of 82, having spent only one month in a Tacoma nursing home.

Chris Woll quitclaimed the land and house to his brother, Anton A. Woll, shortly before his death. The transaction was recorded with the county on Feb. 19, 1963. While I was unable to see the deed, the index shows that the property was in the same section (32), same township (21), and same range (2 East) as the Little House, adding further circumstantial evidence that Chris Woll was indeed the Krist Wall on the 1926 deed, and that he owned it until 1963.

The quitclaim to Anton Woll in 1963 is where the deed trail ran cold. He died in 1966, and never lived on the property.

Today

The current owners acquired the house sometime between 1963 and 1996. The house property is now 4.92 acres, and is adjacent to the current owners’ home, which is the other half of the original 10. That means the house isn’t abandoned, it’s simply now an outbuilding, so please don’t go trespassing across the hayfield to peek through the windows.

And if any of you know the current owners (who will not be named here), tip them off to this story. They may not know much of the early history of The Little House in the Hayfield. I’d bet they’d like to, though.

Photo by Greg Spadoni.

New business: a heartwarming tale of Christmas in Gig Harbor

At the former Spadoni Brothers property at the corner of Stinson Avenue and Rosedale Street, it was an annual tradition to have a decorated and lighted Christmas tree on the sidewalk outside the office. Claude Spadoni, one of the brothers, would go to one of their forested properties, select a Douglas fir, bring it back to the office, and stand it in a galvanized steel pipe buried in the ground flush with the surface of the sidewalk.

In 2004, the last year the business occupied the property during the holidays, Claude was long gone, and the tradition was in danger of being discontinued.

Until I stepped in.

Arriving for work before dawn on Dec. 23, 2004, and having brought a Douglas fir from my own property — the top of a taller tree toppled by a strong wind — I whittled the trunk down with a machete until it fit snugly in the permanent tree stand. I decorated the tree with lovingly-crafted pink and orange bows made from survey ribbon, which I often used while clearing land and building roads. I added two plastic candy canes I found in the office, and bright orange road-marking spray paint, also from my work tools, brought the branch tips to life.

To add a festive, wintery touch, James Artley, with whom I had been working all week, had a can of shaving cream in the trunk of his car, which he generously contributed to the cause. As anyone can see, I used it to maximum effect:

Photo by Greg Spadoni.

A present-day Christmas miracle

Today, after many years without, the tradition of a Christmas tree outside the old office may not have been lost after all. In what is just a common, random occurrence in these parts (but one I’m going to pretend is a miracle of the holiday season), a tree has sprouted in the small gap between the building and the sidewalk. It has grown tall enough to support decorations. And, in what is a second common, random occurrence that I’m also going to pretend must be a miracle, the tree is a Douglas fir!

The spirit of a living tree cannot be denied. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

The sprouting of an old tradition for a new generation. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Next time

The month of December is one of only two months this year where I’ve had to come up with three columns instead of the regular two. The Dec. 29 column will tell the tale of another local Douglas fir. But instead of its beginning, we’ll witness its ending.

Don’t worry, though — it had a good life. It spent its last years on a farm. Just like your beloved dog when you were a kid. “We took it to a very peaceful farm way out in the country where it can run around with the other animals and live happily ever after.”

— Greg Spadoni, Dec. 15, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.