Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The homestead confusion

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

The most satisfying stories of history are both entertaining and informative. Sometimes, though, to understand certain aspects of the past, entertainment has to defer to education.

This is one of those times. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be interesting. This piece at least has an interesting twist near the end. Maybe even two. And it’s got pictures — in color!

If you own a home and refer to it as your homestead, it’s likely everyone knows what you’re talking about. But even if you have a homestead, you are not a homesteader in the traditional sense, and the confusion between the two words (three, if you add homesteading to the mix) can be considerable.

In the days when subsistence farming was common, homestead originally referred to enough land to support a family. In the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. government attached the word to a new law designed to facilitate the transfer of federal land to private citizens without cost: The Homestead Act of 1862. That gave homestead a second definition, referring to land acquired through the act, which sparked the beginning of the confusion.

The law also spawned two new derivative words, homesteader, which was someone who acquired free land by means of the Homestead Act, and homesteading, which described the act of becoming a homesteader. The once-simple meaning of homestead has never been the same since.

Long before the repeal of the Homestead Act, the word homestead casually evolved to describe just about any single-family dwelling on a piece of land. In more recent times, the definition of the word has been further expanded (by law in some jurisdictions) to apply to anything you own if you use it for your residence. So today, no matter where you live, whether in a building, car, tent, or cardboard box, if you also own it, you have a homestead, even if you don’t call it that. But you are not a homesteader in the traditional sense, because you didn’t go through the procedure of homesteading.

The distinctions are normally of no consequence, but they are of significant meaning when applied to the settling of the western United States, and for the purposes of this column, western Washington state in particular. The means by which the first settlers acquired their land tells an important part of their story.

Hard workers

If a family gained their land through homesteading, you can be sure they were very dedicated and hard workers who labored for years to reach their goal of land ownership. It’s also a powerful clue that the family probably had no money with which to buy land, leaving the years-long struggle as their only option. If, on the other hand, the first owners of a particular piece of ground paid cash for it, you don’t know whether they were diligent workers or if they ever lived on the land. They obviously had at least some money.

In many cases cash buyers were indeed every bit as industrious as the homesteaders, building a farm out of nothing and working it for years. But in many other cases, the original owners never lived there. They purchased the land either for the timber on it, or simply on speculation that they could sell it for a profit not too many years down the road.

From the perspective of historical research, the most important difference between the words homestead and homesteader is that true homesteaders, in addition to having had to work their land in order to be granted title to it, also had to submit proof that they had fulfilled all the requirements of the Homestead Act. To the great benefit of those who like to discover the stories of the homesteaded land and the homesteading families, that proof still exists today, and is available to the public in the form of land entry case files. Those files contain enormous amounts of information on both the people and the land that cannot be found anywhere else. The land entry case files for cash purchases are also available, but contain only a fraction of the information found in those for homesteads.

Another important point concerning homesteaders is that they were allowed to gain free land through homesteading one time only. They could file a homestead claim more than once, but only if all previous attempts to complete the process had failed.

Finding original owners

When looking at the full history of a parcel of local property, it is fundamental to first find out the name of the original owner and the means by which it was acquired. The rest flows from there. But when the origin of ownership is simply assumed, or has been distorted by the passage of time, the truth is very often lost.

Perhaps the two best-known homesteads in the greater Gig Harbor-Key Peninsula area are those of Henry Sehmel in Rosedale and William Vaughn in Vaughn.

The Henry Sehmel homestead (the larger portion of which is now the site of Sehmel Homestead Park) is a textbook example of a true homesteaded property. Sehmel filed a claim under the Homestead Act, carved a farm out of the wilderness, worked it for several years, and was granted title to the land for free.

The Henry Sehmel homestead in North Rosedale is a textbook example of the use of the Homestead Act of 1862 to acquire land. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

On the Key Peninsula, however, the William Vaughn homestead was not homesteaded in 1852, as has been written many times. It could not have been, as the Homestead Act was not passed into law until 1862. The idea that it was homesteaded 10 years before it was even possible is simply an error that was repeated often enough over many years until it became accepted as fact. The truth is that William Vaughn never successfully homesteaded on Vaughn Bay or anywhere else.

There have been other notable errors concerning homesteading and homesteaders in the area. Bob Crandall, in his mostly excellent self-published book, “Rosedale,” commented: “The thing that amazes me seems common among the homesteaders. Very few of them developed their land. They proved up and sold out.”

Mr. Crandall, with all good intentions, misread the original land deeds he found for North Rosedale. He referred to them all as Homestead Certificates, when in fact over half of them were not. The majority were land patents issued for the purchase of the properties for cash, not homesteading.

The reason many of the original North Rosedale land owners sold out without developing their property is because they had purchased the land either for the timber it held or for speculation, not because they intended to live there, which they did not. And the cash buyers did not prove up, as there were no requirements of a cash purchase to be met other than the cash itself.

Carved in stone

The Artondale Cemetery sign was erected in memory of Lita Wagner. Many of her Gig Harbor relatives are interred there as well, including Blackwood, Cosulich, Seghieris, Spadonis, and Donatis. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

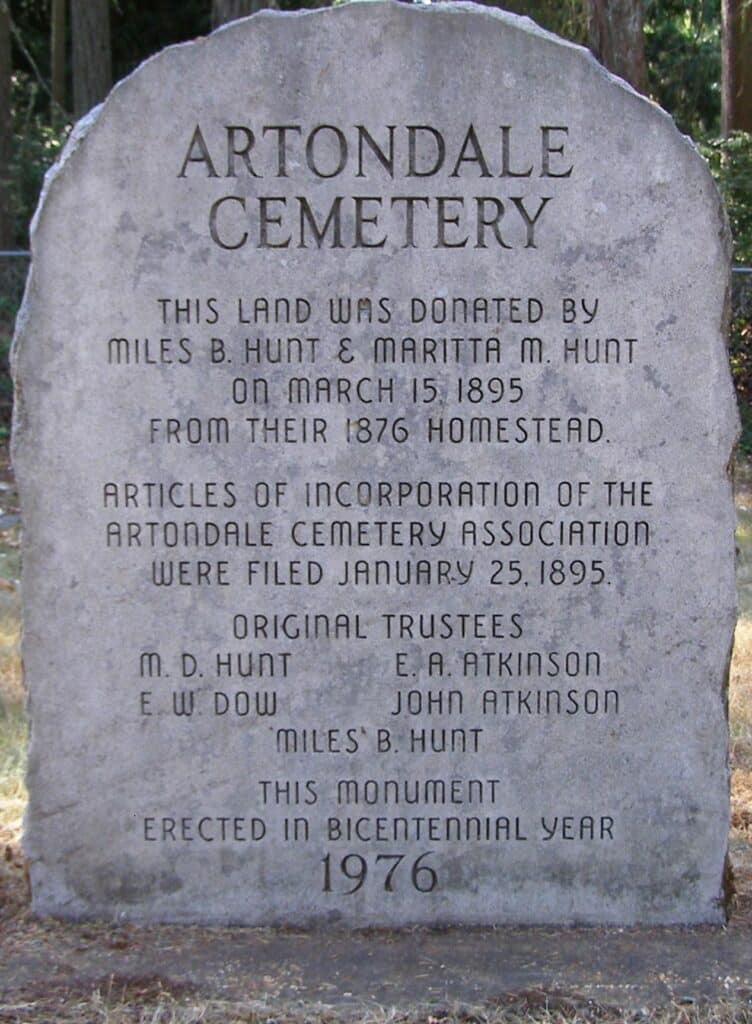

An enduring example of the confusion surrounding the words homestead, homesteader, and homesteading can be found in the Artondale Cemetery on Hunt Street. It endures because it’s literally carved in stone. It is a monument erected in 1976 honoring the founders of the graveyard on what was assumed to be the 100-year anniversary of their homestead. It says, in part, This land was donated by Miles B. Hunt & Maritta M. Hunt on March 15, 1895 from their 1876 homestead.

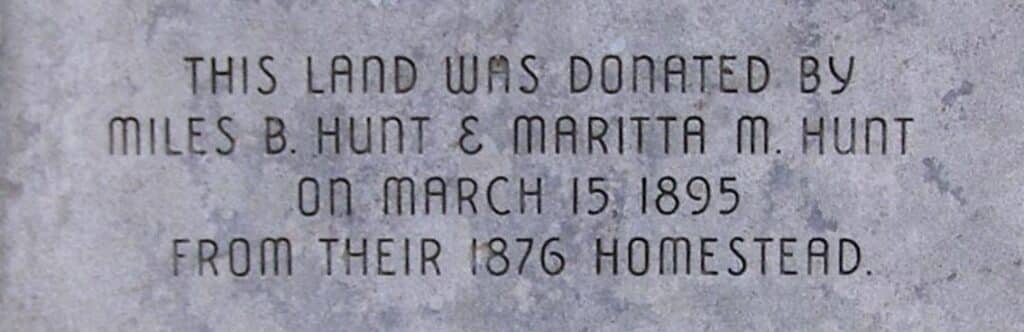

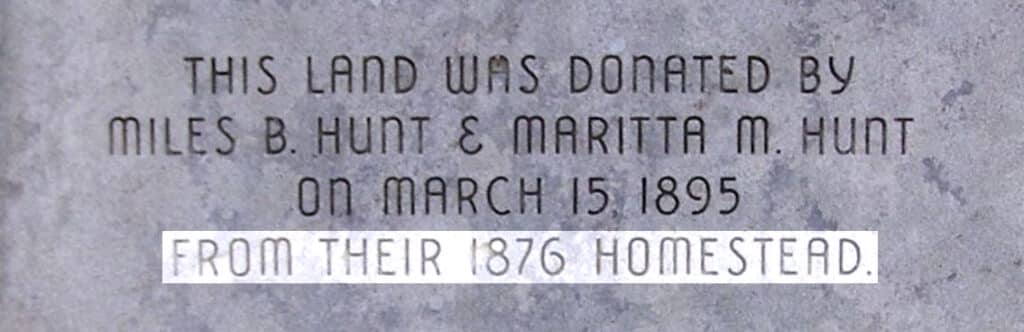

Just because something is carved in stone doesn’t mean it’s true. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Something was obviously misinterpreted somewhere along the line in the 81 years between the donation of the land and the creation of the monument, for it’s not true.

The land in question, the 2.75 acres that make up the cemetery, is located in Pierce County, Washington. Miles and Maritta Hunt’s 1876 homestead, which they acquired through the Homestead Act of 1862, was in Buffalo County, Nebraska. Someone providing information to the monument makers in 1976 apparently mistook the Hunts’ homestead documents relating to the land they homesteaded in Nebraska for their later property in Artondale.

Although it’s carved in stone, the Hunts didn’t donate the Artondale Cemetery land from their 1876 homestead, which was in Nebraska, not Washington. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

In reality, the Hunts didn’t homestead their Artondale land, from which the cemetery acreage was donated. By law, they couldn’t, due to having already successfully homesteaded in Nebraska. They purchased the 80 acres in Artondale from Donald Oliver, who was the first private owner.

He didn’t homestead it either. He bought it from the federal government for cash. The Hunts bought it in 1881,* not 1876, as the stone monument states. So, while the land may have been the Hunts’ homestead at the time of the cemetery donation, it was never homesteaded by them or anyone else. Their homesteading happened entirely in Nebraska, not Washington. Confusing? Maybe a little. But as we’ve seen, the differences can be important.

Squatters were not homesteaders

Another example of the distinction between homestead and homesteader is the local land that was not available for homesteading. Because you could not be a homesteader unless you acquired land through the Homestead Act, none of the original land owners on the entire east side of Gig Harbor were homesteaders.

The same applies to about 300 acres on the opposite side of the bay, about 600 acres at Point Evans (north of the approaches to the Narrows Bridges), and about 600 acres at the tip of Point Fosdick. None of the original settlers on those approximately 2,100 acres were homesteaders, no matter when they arrived there. Federal law did not allow homesteading on those four places. All the settlers there had to buy their land.

But make no mistake, almost all of them were every bit as dedicated and hard working as the true homesteaders were. The fact that they were not homesteaders in the strict definition of the word does not diminish the strength of their characters or the level of their accomplishments. Subsistence farming, which is what most of the early settlers were engaged in, was always physically demanding, and sometimes psychologically so, no matter whether you purchased your land or received it for free.

Judicious use of the word

In most instances the word homestead can be used rather casually. It’s when the original ownership of a particular property is concerned that it should be used very carefully. Understanding the full history of the land depends on it.

*A second deed was issued in 1885 on the very same property, probably to correct an error in the 1881 deed.

Item of Mystery

Yes, the impossibly difficult (except to Tonya Strickland) Item of Mystery has descended into tedium, but we’re not quite out of clues. This week’s goes like this: While 160 of these were used in their original application, later uses required 320.

Next time

Before any bridge was built across the Narrows, the Gig Harbor Peninsula was limited to boat transportation to and from Tacoma. From 1890 to 1911, a series of big plans were made to add another means. The title of the March 24 Gig Harbor Now and Then column is A Freight Railroad for Gig Harbor … unless something more timely comes up.

A joint venture between Gig Harbor Now and Then and Two In Tow & On The Go is currently underway. Not unlike Beach of Dreams, it’s a combination present-day adventure and historical examination. The timing of publication hasn’t yet been determined, so it’s possible it could run on March 24.

The two Beach of Dreams columns in January were very popular. Will the new project be as successful? No telling. Instead of real estate, it concerns discarded photographs over a hundred years old, discovered by accident. What can we find out about the people in those pictures? Hint: a lot.

Greg Spadoni, March 10, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.