Business Community Education Government

Legislation makes opening a child care a little easier

As Kimberly Shaw recalls her arduous four-year journey to open the first licensed child-care center on the Key Peninsula, she holds an infant boy in her lap.

Getting a permit for a child-care center has been more difficult than Shaw, director of the nonprofit Key Peninsula Cooperative Preschool, initially envisioned. The process has been filled with stressful moments. Enough, she jokes, to take years off her life.

The children, though, kept her motivated.

“I mean look at this guy,” she says, glancing down at the boy. “They look at you like ‘I need this’ and you think ‘Ok. I’ll give you the world.’”

A child care crisis

Cumbersome building regulations have long been unfavorable to those looking to open child care businesses, experts say. Zoning restrictions and conditional-use permits required by many jurisdictions often discourage their development.

Seeking to expand access to child care, state legislators have taken an ax to much of the bureaucratic red tape. A pair of new laws aim to streamline the permit process and allow licensed child care in more areas.

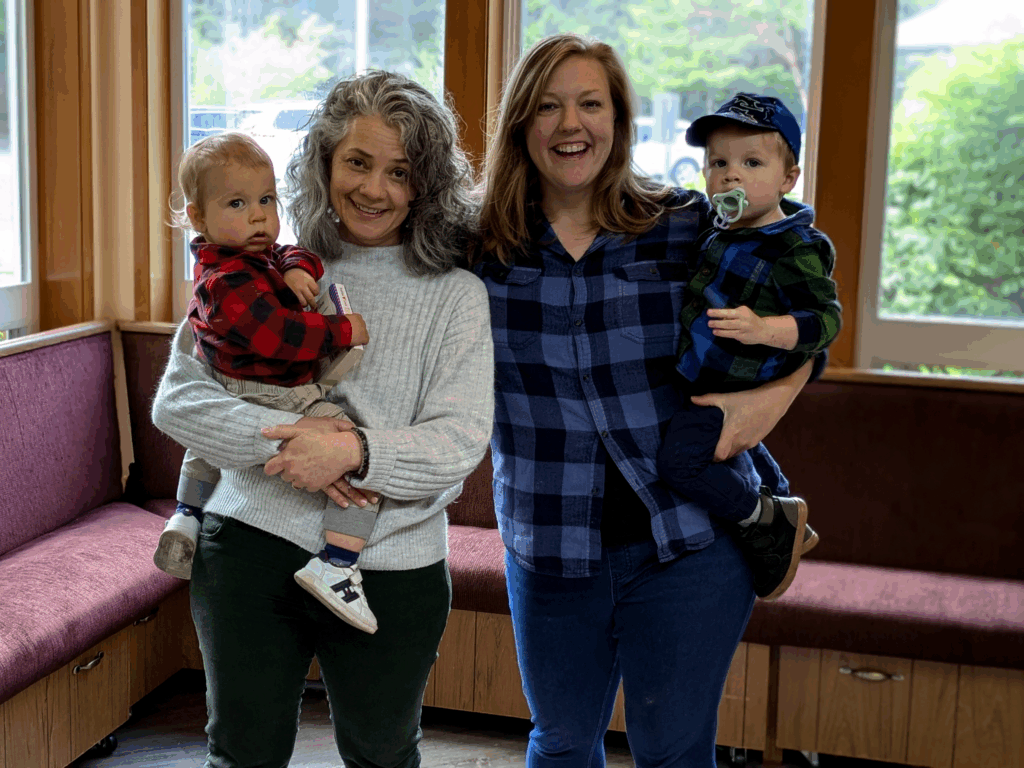

Kimberly Shaw, left, director of the Key Peninsula Cooperative Preschool and Operations Manager Christine Luna, pose for a photo at the Key Peninsula Lutheran Church. Photo by Conor Wilson

The polices are a departure for the state, where previous efforts to expand child care access largely focused on providing subsidies. They come as access to care is still considered insufficient and unaffordable.

One estimate cited by legislators found that about two-thirds of Washingtonians live in a child care desert, according to the Center for American Progress, a progressive policy institute. That means their community has three times as many children as licensed child care slots.

Cities and other jurisdictions, while not involved directly in child care development, can align their code to encourage these projects, said Lisa Pool, a public policy consultant for the Washington-based, nonprofit Municipal Research Services Center.

“To meet ambitious affordable housing goals, many local governments have recently begun to waive fees, expedite permitting timelines, and create additional regulatory flexibility,” she wrote in a blog post. “Such policies can be replicated to support the development of cost-effective childcare facilities.”

Zoning exclusions

Outdated and exclusionary land use policies have long been a barrier to expanding child care in Washington, said Chetan Soni, political action manager for the Children’s Campaign Fund Network, a nonpartisan PAC focused on children’s issues.

Most cities typically allow child care in areas zoned for commercial or residential use, but often only on a conditional basis. That stipulation means projects require additional reviews and approvals. That can add time, uncertainty and costs.

A new law sponsored by Sen. Emily Alvarado, D-West Seattle, removes many of those barriers. The legislation requires cities and towns to allow child care centers as an ‘outright permitted use’ in most areas. The law excludes industrial, light industrial and open spaces.

“This bill is simple but powerful,” said Soni, whose organization testified in support of the legislation, said. It “begins to treat child care as essential infrastructure.”

Weeks, not months

Designating child care centers as an “outright use” significantly reduces the time required to approve a permit, said Gig Harbor City Administrator Katrina Knutson. They no longer require public notice, a state environmental assessment or review by the city hearing examiner.

“Without the conditional-use permit, that’s more like a six-week process versus a four- to six-month process,” she said.

Knutson said city officials routinely hear from residents and the Chamber of Commerce about the need for more child care in Gig Harbor. Lots of in-home daycares closed during the pandemic, she said. The vast majority did not return even as the population grew.

Gig Harbor’s current code restricts where child care facilities are allowed and also has stricter conditional permit processes within most of those zones, Knutson said. Prior to the new law, Knutson estimated child care was permitted in about a quarter of areas in the city. Now she says that will likely be around three-fourths.

Key Peninsula

Zoning was also a challenge for Shaw on the Key Peninsula, which has few commercially zoned areas. That left churches as the only viable place for a child-care center, she said. She found that operating within a pre-established space came with its own regulatory barriers.

The Key Peninsula Co-Op Preschool has been a staple in the community for 50 years, said Christine Luna, the school’s operations manager, offering care for those ages 3 to 5 for a few hours each week.

Kimberly Shaw, director of the Key Peninsula Cooperative Preschool, lifts a student at the Key Peninsula Forest Friends and Nature School on June 4. Photo by Conor Wilson

But parents wanted something more, she said. The closest full-time child care services were in Port Orchard and Gig Harbor. There was nothing for parents on the Key Peninsula, especially for those younger than 3.

“That’s the message we keep getting from our families: ‘We need full time child care out here because there is none,’” she said.

“We’re in an economy where you have to have dual income – you have to,” she continued. “There’s so many moms out here that are trying to work from home, they’re trying to raise their children and that’s just impossible. Something is going to fall, and a lot of the time it is our students that are falling.”

After receiving a $150,000 grant about four years ago, Shaw and Luna planned to open a licensed child care center in the basement of the Lakebay Community Church. They wanted to serve 35 children ranging from 3 months to 5 years old. Then they hit an obstacle.

Fire codes

The church – which Shaw says has about 25 congregates — has a maximum capacity for up to 300 people. To get a license for the basement, a requirement to receive state subsidies, the whole building needed to meet fire code for its maximum occupancy.

They were asked to put in a larger sprinkler system, as if 300 people would show up, Shaw said.

“They said the potential is you could have 300 people – and they could show up at the same time as the 35 children downstairs, so you have to put in this giant sprinkler system,” she said.

She said that project would have cost several thousand dollars. Unable to open indoors, Shaw and Luna pivoted. They repurposed the grant funds to open a forest school at a nearby Lutheran Church. They were allowed to serve children, so long as they never went inside.

That school has been thriving since it opened, Shaw says, providing childcare for the first time on the Key Peninsula, with some limitations. Since the school is fully outside, state law prohibits them from serving children younger than 30 months.

That has left many families without nearby care. The co-op got a permit for an eight-child room for infants at the Lutheran Church, but Shaw says that is hardly enough. That room is currently serving only the most needy children in the area, she said.

Samantha Henderson, a teacher at the Key Peninsula Forest Friends and Nature School, hands chalk to a student on June 4. Photo by Conor Wilson

Church basement child care

Working alongside Pierce County Councilmember Robyn Denson, who represents Gig Harbor and the Key Peninsula, state Sen Deb. Krishnadasan sponsored a bill that should open up the Lakebay Church basement as a potential child care facility.

“The existing law creates nearly insurmountable barriers for those looking to open new child care centers, especially in our rural communities,” Krishnadasan, D-Gig Harbor, said in a statement. Denson could not be reached for comment.

The legislation allows child care centers operating inside pre-established spaces, like churches, to open if they meet the fire code for the section of the building they are occupying.

It’s a slight tweak that could finally allow childcare for children as young as 3 months old on the Key Peninsula. Shaw and Luna say they intended to begin fundraising and to open the basement space in the Lakebay Church.

“It is very subtle, but significant to us,” Luna said of the law change. “It has opened the doors.”