Education

No class schedule disruptions, but Peninsula teachers ‘overwhelmed’ from filling gaps

Earlier this month, Peninsula School District informed families that temporary disruptions to bus routes would become semi-permanent pending resolution of a driver shortage plaguing school districts everywhere. On Nov. 8, the district eliminated some routes and consolidated others, adding stops to some.

Education Sponsor

Education stories are made possible in part by Tacoma Community College, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

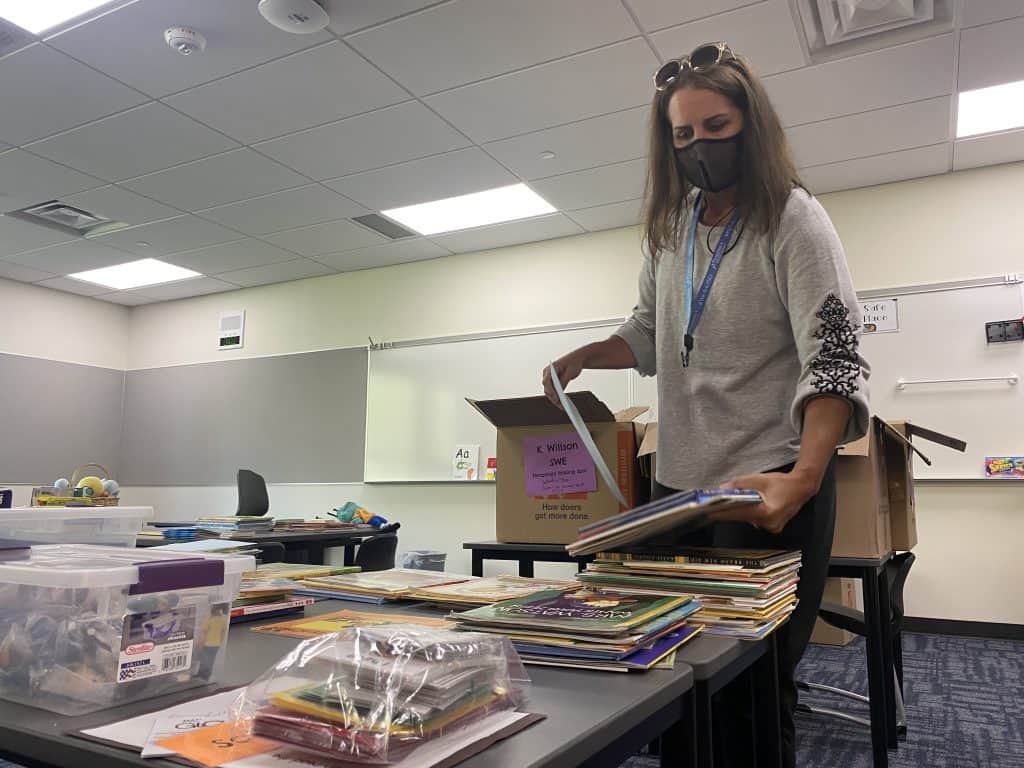

Kindergarten teacher Kelli Willson sets up her classroom at the new Swift Water Elementary School. Christina T Henry / Gig Harbor Now

Across the United States, school districts have been hobbled by staffing shortages related to the pandemic that have disrupted transportation, food service and teaching. Some districts have taken radical steps like temporary class closures and a return to online learning. Peninsula’s not there (yet, at least), but teachers and other learning specialists are experiencing the burnout reported nationwide as they fill in gaps and step up to extra demands created by the pandemic.

“People say they were ‘December tired in October,’” said Carol Rivera, president of the Peninsula Education Association.

The district technically has enough classroom teachers, but began the year with some vacancies for teaching specialists like occupational therapists and speech pathologists, according to Rivera.

“But we’re now in November,” she said. “What that means is their colleagues who are in the district have picked up that additional workload, whether it means servicing another school that maybe didn’t have someone dedicated or pick up a day or two here or there.”

The annual churn of school staff was greater this year than usual.

“We had close to 100 staff leave the district either for retirement or resignations,” Rivera said. “I think, obviously, last year was pretty challenging. I think that some people made some choices to take earlier retirement than they normally would have. Because of circumstances with the pandemic, a lot of our providers can go work in private practice, or in hospitals or in other areas.”

There’s less wiggle room this year

Caroline Antholt, director of human resources, said the district is “not experiencing a shortage of teachers. We would like to hire more subs to give us more ‘wiggle room’ when we have days when more staff are out sick or are on vacation.”

That lack of wiggle room adds up to a thousand cuts of exhaustion, Rivera said. She’s noticed an acceleration of the phenomenon known only too well to those in the teaching profession when holiday breaks promise sorely needed respite and a chance to recharge.

“The best word to describe it is they’re ‘overwhelmed’ at this point in the year. And I would say it actually happened earlier this year than normal,” she said.

The substitute teacher shortage has compounded staffing issues for districts, some of which have been harder hit than others. In North and Central Kitsap, school principals and other administrators are stepping in to teach classes in large part because of a lack of subs, the Kitsap Sun reported.

In addition, pandemic protocols mean teachers have even less flexibility when one of their colleagues is out sick or takes a day of leave. In Peninsula schools, one strategy in the past was for several teachers to take students from the absent teacher’s class for a day.

“You spread the kids out and they’re able to engage in their grade-level learning, that sort of thing,” Rivera said. “But we can’t do that because we have space restrictions, right?”

Instructional staff are using planning periods to cover for their peers. And with bus routes being cut and some parents driving their kids to and from school, students arrive earlier and leave later, needing supervision in the classroom.

“It just makes for a very long day,” Rivera said. “And so, it’s contributing to that burnout and just being overwhelmed.”

She and other union leaders have started a conversation with district officials about teachers’ mental health and wellbeing. The district has been receptive, Rivera said.

High expectations hampered by more responsibilities

This school year began with high expectations for students and teachers, among them the goal of making up “lost learning.” Rivera says the media and educators themselves have latched onto that narrative in a way that’s added pressure when students and teachers, alike, are sometimes struggling to regain a rhythm with in-person school five days a week.

“I think there was this sense, ‘Oh, we’re going back. We’re going to be able to resume things as normal.’ But, you know, there’s just so many other responsibilities,” Rivera said.

The focus of discussions between the union and the district, according to Rivera, has been how to “reprioritize, what are the things that are our guiding lights that we really need to focus on this year … and what are the things that we can probably take off the plate?”

Rivera says the social-emotional health of students needs to remain a high priority.

The union has received a $10,000 planning grant from the National Education Association to map out strategies for shifting the district’s culture toward encouraging educators to exercise self-care.

A committee of union members has been asked “to really think about the work we do with our students and what those priorities are and how we as educators maybe set more professional boundaries for our own wellbeing,” Rivera said.

There could be more money from the NEA to implement the proposal, which is due to be submitted in February.

Both Rivera and Superintendent Krestin Bahr say there’s much to celebrate even amid the new challenges this school year.

Bahr said she’s seen staff members across the district come together to support one another, “never losing sight of our purpose — the children.”

“As educators, we provide both social and academic structures for children. This fall, teachers have needed extra time with students to reestablish school routines, social norms and expectations for what it is to be a student in-person, five days a week,” Bahr said. “At the same time, we’ve expected teachers to assess students academically, both from the state and local level. It’s been a busy time, but a joy to watch our teachers working very hard doing what they love.”

“Our teachers really do need to be recognized and celebrated for what they do as professionals,” Rivera said. “You know they’re some of the most creative, dynamic and caring people on the planet.”