Community Education

Peninsula schools make course correction on teaching reading

One of Peninsula School District’s goals is for all students to be functional readers by the time they complete third grade. Achieving that goal would require 100% to meet grade level standards in English language arts on state assessments by 2026.

Education Sponsor

Education stories are made possible in part by Tacoma Community College, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

District officials note that children who have not learned to read by third grade are statistically less likely to master other subjects as they move through the K-12 education system. It’s a pivotal year, with huge consequences for a child’s future.

Yet the most recent literacy data posted on the state’s education website shows that nearly 40% of Peninsula third graders were reading and writing below grade level expectations in language arts. In K-12 districtwide, only 65% met the standard.

“Year after year, when we examine our data, we’re not satisfied with it, the number of students who are meeting benchmark, reading at grade level,” said John Yellowlees, chief academic officer for teaching and learning.

Course correction coming

Yellowlees cited dismal reading data as one of multiple factors driving a systemic course correction for how Peninsula School District teaches students, especially those in early elementary school, to read and write.

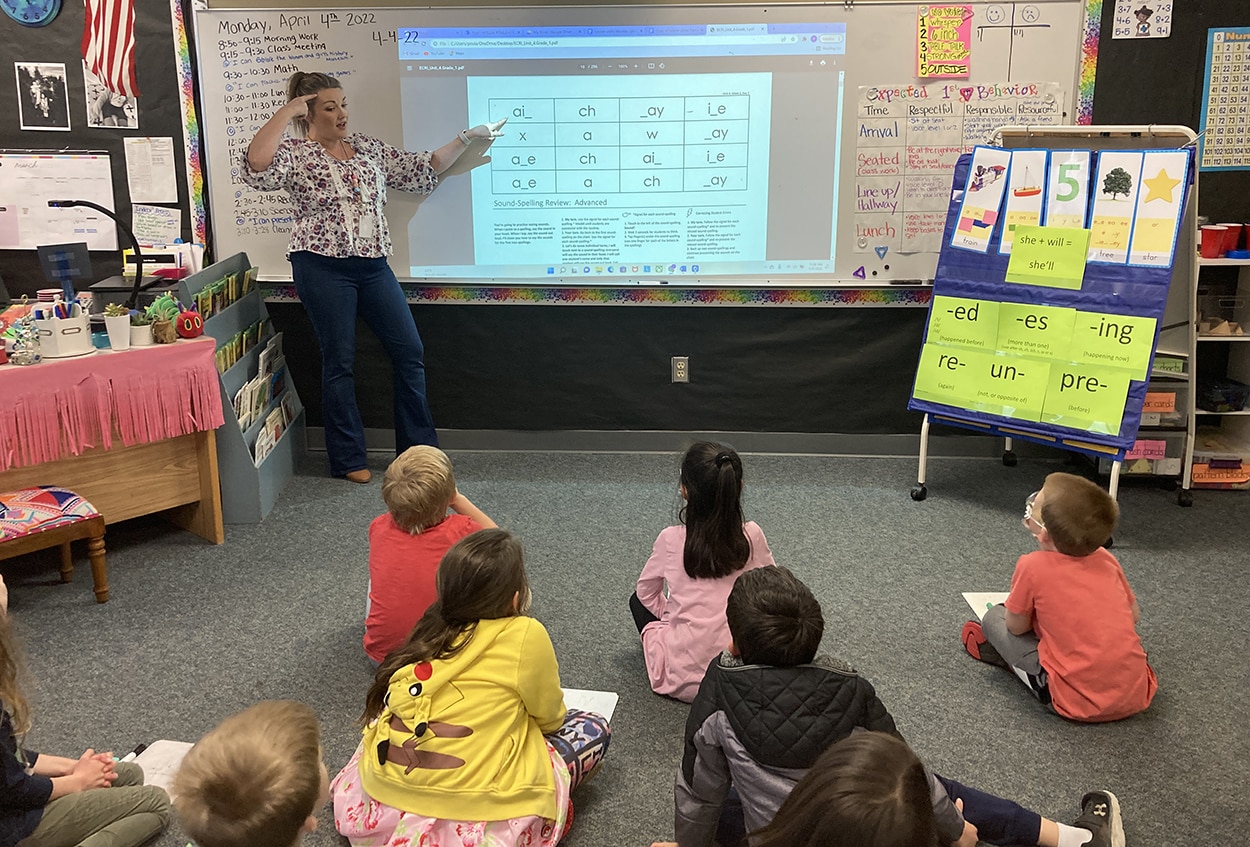

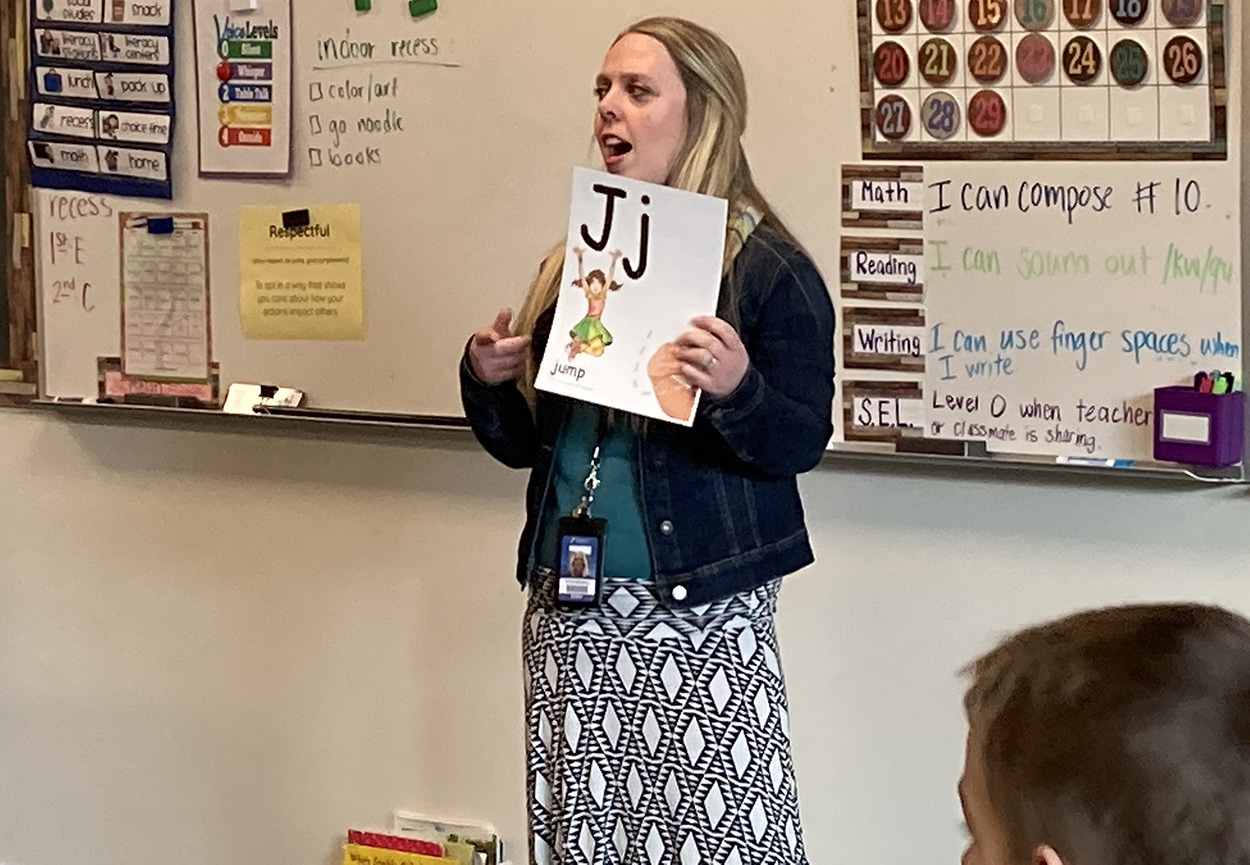

Peninsula School District is embracing the “science of reading,” which identifies five essential components for reading instruction, including phonics.

Photo courtesy Peninsula School District

In June, the district’s Literacy Task Force outlined plans to retrain its elementary teachers in evidence-based methods to teach children to read. They will use these methods consistently across classrooms, grade levels and schools, district officials say. And they will be better equipped to help students struggling to read.

It’s about time, say members of a parents’ group whose children have dyslexia. Two families from the group have sued the district, alleging it failed to provide their children adequate reading instruction. A judge in both cases ruled in the families’ favor. The district is appealing one case.

What’s not working?

One key piece of the proposal, according to Yellowlees and other administrators, calls for eradicating remnants of “Balanced Literacy” teaching methods. This trend in education rose to widespread popularity in the 1980s and 1990s. It is now widely recognized as mostly ineffective and potentially harmful.

Students taught in this methodology, also called cueing, are asked to figure out a word they don’t know based on the context of the sentence and from pictures on the page, among other prompts. So, basically, guessing the word until it becomes familiar.

Cozy reading nooks and exposure to lots and lots of books will engender a natural ability to read, the theory goes. Except that decades of research show it doesn’t.

A recent podcast from American Public Media tracks the rise and fall of Balanced Literacy. The series indicates that Balanced Literacy’s flaws are not so much about its intent — to develop a love of reading in children — but what it omits.

Proponents of Balanced Literacy recommended against a focus on phonics, or teaching children the relationship between letters and sounds. Instead, they advocated a “whole word” approach.

That works fine for some kids, typically the ones to whom reading comes most naturally. But it can leave others in the dust, especially those with learning disabilities related to reading, like dyslexia.

Canary in the coal mine

School board member Jennifer Butler, a member of the Literacy Task Force, said during the June 22 presentation of its findings that the pandemic was a wake-up call for her and many other parents. Sitting beside her then-kindergartener during remote learning, Butler said, “for the first time, I was seeing ‘she’s not learning to read the way I learned to read.’ ”

Parents of students with dyslexia had “known for a while,” she said. “Then COVID kind of blew the door open. Now all parents were starting to say, ‘What’s going on? Like, what are we doing? Why are we asking kids to guess? Why are we not teaching them to sound out words anymore?’ ”

Peninsula School District is making systemic changes in how students, at least at the elementary level, are taught to read. The goal is for all elementary teachers to receive training in the “science of reading,” which outlines how people learn to read and five essential components for a reading instruction program: phonics, phonemics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Photo courtesy Peninsula School District

Peninsula School District is not alone, Butler said. “This is a national conversation that’s happening.”

The district’s Reading Wonders curriculum does teach phonics, according to Yellowlees. But since 2021, Peninsula K-3 teachers used a supplemental methodology called ECRI (Enhance Core Reading Instruction) to provide “explicit and strategic instruction in phonics and phonemic awareness.” Teachers had been asking for instructional tools to fill the gaps, Yellowlees said.

Members of the Gig Harbor Peninsula Dyslexia Parent Group say ECRI falls short of the systemic fix to reading instruction that’s needed at all grade levels.

One family’s fight

Michael Perrow knows the frustration and humiliation of dyslexia. A former Gig Harbor city councilman and local business owner, Perrow struggled to read as a student in Peninsula School District. Fortunately, his mother was a teacher. She tutored him intensively and he learned to read and write, using coping skills that he still relies on to adapt to his disability.

Dyslexia is a neurological condition characterized by difficulties with word recognition. Typically, this results from a deficit in the phonological component of language, the ability to relate the sounds of language to letters and words on a page. “With the right instruction, almost all individuals with dyslexia can learn to read,” says the International Dyslexia Association.

But Perrow asserts the right instruction was lacking when he was a student. He believes little had changed by the time his son and daughter, both of whom have dyslexia, entered the system.

Perrow and his wife Kelly Perrow filed suit through the state’s Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction on behalf of their daughter, who is entering fourth grade and who is severely impacted by dyslexia. They say they pursued legal action not only to benefit their daughter, but to pressure the district to make systemic changes in its literacy instruction that will benefit all students.

‘We have to be the advocate’

Kelly Perrow, who taught reading in the district for 10 years, has tutored both their son, now in sixth grade, and their daughter since before the pandemic.

The Perrows also accessed private tutoring that helped both of their children. But they worry about those who can’t afford tutoring, or who live out on the Key Peninsula, making tutoring logistically unrealistic. And it’s not only students with dyslexia who need help, they say. Just look at the literacy data.

“This isn’t about our kids. This is everybody,” Kelly said. “We have to be the advocate. We need to make some change.”

Their judge in July found that the district had failed to make an appropriate special education plan for their daughter over a two-year period and had failed “to provide her with an evidence-based, structured literacy program for students with dyslexia” until March 2023.

Settlements

The district has been ordered to reimburse the Perrows for professional assessments and instructional materials used at home. The award totals more than $12,000. In addition, the district must to pay for 270 hours of tutoring at a cost of up to $200 per hour. The judge also required the district to conduct staff training as part of a “corrective action plan.”

In the second case, the judge reviewed testimony from the family of a girl with dyslexia, now in eighth grade, who suffered from extreme anxiety related to her disability and who required clinical intervention.

The girl’s mom said they got tutoring for their daughter, which helped. They ultimately moved her to a private school because they couldn’t get the help they needed from the district. The judge agreed, ordering the district to reimburse the family for up to $5,000 in tutoring costs and to pay for an additional 20 hours of tutoring. The mom said the district also paid their attorney’s fees, around $60,000.

The district has appealed the Perrows’ case, according to that family. District officials declined to comment on either case.

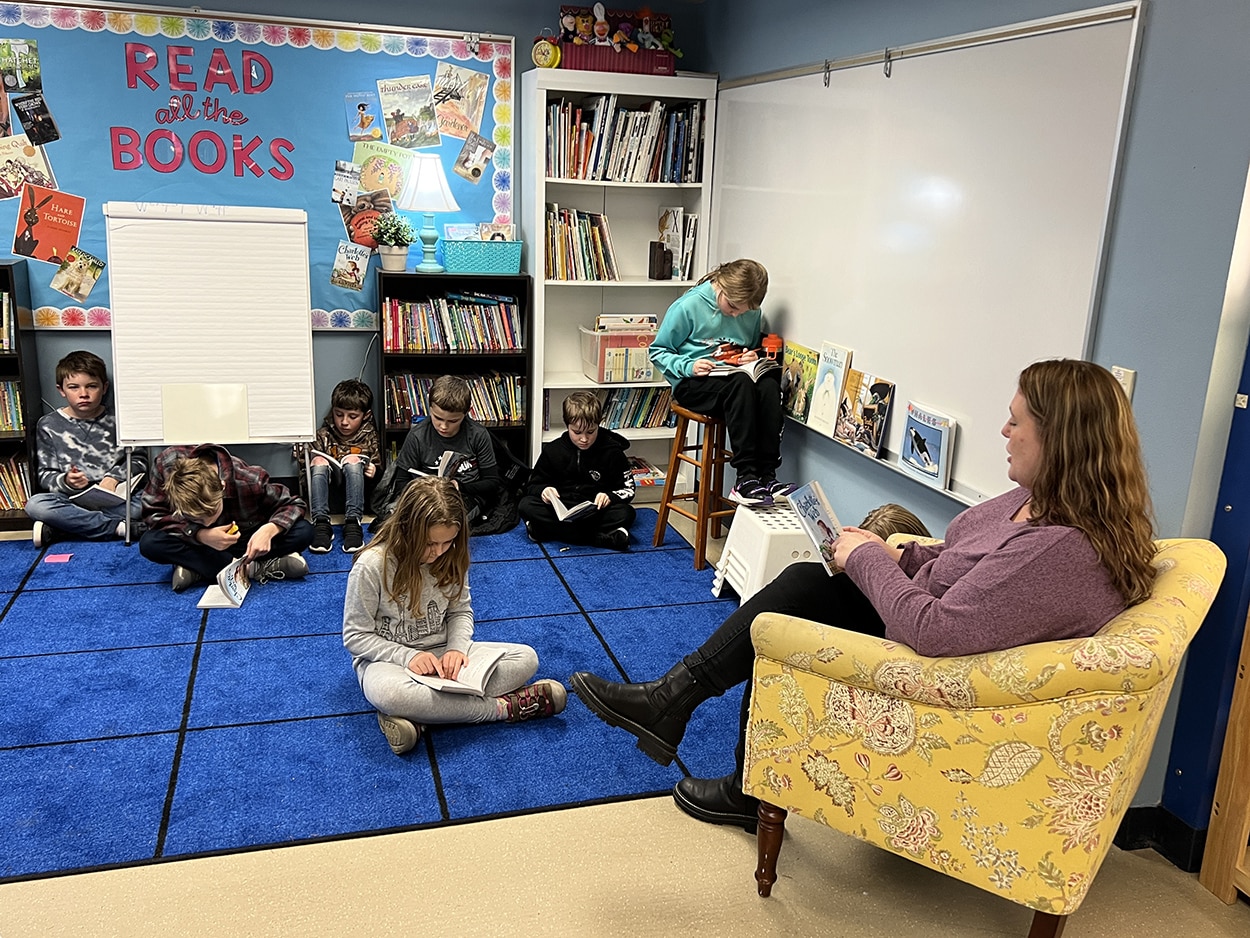

The Peninsula School District will still employ reading aloud and independent reading, which supports direct instructional methods like phonics and which can help kids learn to love reading. Photo courtesy Peninsula School District

Dyslexia Parents’ Group proposal

The Perrows have taken leadership roles in the Gig Harbor Peninsula Dyslexia Parent Group, with at least 40 families who are “core members” and another 60 who have attended a meeting here and there. Families come seeking support, guidance and resources, Michael Perrow said.

In March, the group presented a proposal to the district for substantive changes in how teachers are trained and what curricula they use to teach literacy.

The written proposal charged that the district’s methods “are ineffective based on current research and best practices.” It calls for teacher training across the board in what is now known as the “science of reading.” The term refers to a body of research outlining how the brain learns to read and components of a successful instruction program, which include phonics. And it calls for a curriculum that delivers that instruction in a manner that is “structured, sequential and explicit.”

It’s not that some of this isn’t already happening at some level in the district. But inconsistency from teacher to teacher, class to class and school to school is a huge problem, Michael Perrow told the board March 23.

“Right now, it’s a mishmash of whoever, whatever,” he said.

The Perrows say parents have been asking for change for years and that change has been needed for decades.

“What are we waiting for?” Kelly Perrow asked the board. “Learning to read isn’t magic. Learning to read takes incredible effort.”

She acknowledged that no single curriculum is the “silver bullet.” However, she said, “if teachers have a way to teach explicitly and systematically, students will and can learn to read.”

Reading task force gets to work

Three months before the parent group’s proposal to the board, Superintendent Krestin Bahr had convened the 100% Reading on Grade Level Task Force. It comprised parents, teachers (some of whom have children with dyslexia), principals and others, including regional literacy experts. Kelly Perrow was invited.

The group spent the winter and spring researching the science of reading, teacher Marci Cummings-Cohoe said at the June 22 board meeting. They learned about the five essential components for learning to read (as outlined by the National Reading Panel in 2000).

The NRP, convened by Congress in the late 1990s, analyzed decades of scientific research on how children learn to read. Their findings are encompassed in what is now known as the science of reading.

The five essentials include: phonics (teaching the correlation of sounds with letters or groups of letters); phonemic awareness (the ability to focus on and manipulate phonemes or units of sound in spoken words, like the “mmm” sound in “mat”); fluency (the ability to read with speed, accuracy and, if aloud, appropriate verbal expression); vocabulary; and comprehension.

The task force learned the difference between Balanced Literacy and Structured Literacy, which focuses more on the structures of language. They reviewed reading data, and they visited local and regional schools where structured literacy methods are being used with success.

Peninsula School District is making systemic changes in how students, at least at the elementary level, are taught to read. The goal is for all elementary teachers to receive training in the “science of reading,” which outlines how people learn to read and five essential components for a reading instruction program: phonics, phonemics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Photo courtesy Peninsula School District

What the task force found

Through its research, the task force learned that literacy instruction should be “systematic and explicit,” according to its presentation.

Teaching literacy requires consistency across the board. And instruction should include multi-sensory opportunities for students, such as tracing letters with their fingers. Schedules, especially for older students, should prioritize blocks of literacy instruction.

The district should have an array of systems in place and accommodations to support students with their individual needs, the task force says. An example would be allowing a student to have test questions read to them. Supports should exist within a network of interventions for academic and social-emotional needs. The district has been working on that support network since 2019, according to Yellowlees. It remains a work in progress.

The way forward

The biggest take-away from the task force is that teacher training is “paramount” to the success of a district’s literacy instruction, according to the group’s June 22 presentation. Most districts they visited were using the LETRS teacher training (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling). That, they say, is the way forward.

LETRS is an instructional program for elementary educators that teaches the science of reading. It covers how the brain learns to read and imparts instructional methods that address each of the five essential components of reading.

The district has signed up 80 teachers in kindergarten through fifth grade who volunteered to receive the training this school year. In 2024-25, the district will require the training for all K-2 teachers and all elementary reading specialists who didn’t participate this year.

“Our goal is to extend the opportunity to all elementary teachers once we’ve met our commitment to training the priority groups listed above,” Yellowlees said.

Four staff members will complete LETRS facilitator training, so that the district can conduct its own training of incoming teachers and those who need a refresher.

Teaching colleges are woefully behind the curve, said Yellowlees. According to him and other administrators, new teachers are coming out of college never having heard of the science of reading. So at least for now, it’s up to districts to fill the gap.

Peninsula School District is embracing the “science of reading,” which identifies five essential components for reading instruction, including phonics.

Photo courtesy Peninsula School District

What about secondary students?

The focus of the task force was on early elementary education. The metric of 100% third-grade literacy was front and center. The group’s vision, part of its “Guiding Principals,” goes broader. The vision states that “all students will read at or above grade level and receive support from pre-k through graduation grounded in the science of reading.”

The vision encourages Ginger Tannenberg, a middle school teacher who served on the task force and whose son has dyslexia. “It’s the most work I’ve seen happen in our district in the 13 years that I’ve been here,” she said.

She thinks the plan to train elementary teachers in the science of reading will be a game-changer. Tannenberg, however, is concerned that secondary students may not reap the benefits of the plan, at least initially.

“That has been one of the things that came out of the task force as well, that our need was really more than just that early literacy,” said Lisa Reaugh, the district’s executive director of student services and a task force leader. “We want to start strong, so we don’t have those needs, but we have gaps for those kids that have missed some things or maybe have dyslexia and didn’t get the instruction they needed.”

Reaugh said the district this fall will pilot some middle school “intervention models.” Unclear is exactly what those would look like. At the high schools, the goal will be to get teachers more familiar with accommodations that could be offered to individual students. And, said Reaugh, the district is hoping to tap into assistive technologies, like A.I., to aid students struggling to read.

A tale of two teachers (the pendulum swings yet again)

Reaugh and task force member Natalie Boyle, director of elementary teaching and learning, were young teachers in different school districts roughly 20 years ago, when the national debate over childhood literacy was in full swing. Despite the NRP’s evidence-based rationale for phonics and phonemics, many remained loyal to Balanced Literacy.

The affluent Issaquah School District, where Boyle taught third grade, was in the Balanced Literacy camp. If kids were struggling, they probably had tutoring.

“I got kids who mostly had some of those early learner literacy skills down, but I was not a fan,” Boyle said.

Reaugh, meanwhile taught in a high-poverty district in Tacoma that received funding from the George W. Bush-era Reading First program, which emphasized phonics. The program was successful, Reaugh said. More-affluent schools in her district that hadn’t even heard of Reading First became interested to try it.

Then, the pendulum began to swing. Balanced Literacy became the favored technique.

“And now we’re heading back the other way, and it’s hard to move systems,” Reaugh said. “You get people really entrenched in their beliefs and what they think is right and what they’ve read and experienced. So, we are working through that by helping teachers understand how research should drive their work.”