Community Environment

The ‘Jonny Appleseeds’ of Manila clams and Pacific oysters

If your go-to shellfish order at a restaurant is a basket of steamer clams, it’s likely you’re eating a species that ended up in Washington by accident.

Also known as “Japanese littlenecks,” Manila clams are originally native to the Northwest Pacific — not the Pacific Northwest, intertidal biologist Jack Dudding told attendees at the Key Peninsula-Gig Harbor-Islands (KGI) Watershed Council’s annual State of the Watershed meeting on Oct. 29.

“We think [Manila Clams were introduced] in the 1920s, 1930s — kind of unclear, but it became a major aquaculture species,” Dudding said. “It’s grown throughout Puget Sound. It’s a huge source of revenue for a lot of aquaculture companies. [You can] get it everywhere. If you order steamer clams, that’s what you get: Manila clams. They’re recreationally harvested and managed by [Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife] WDFW on public tidelands.”

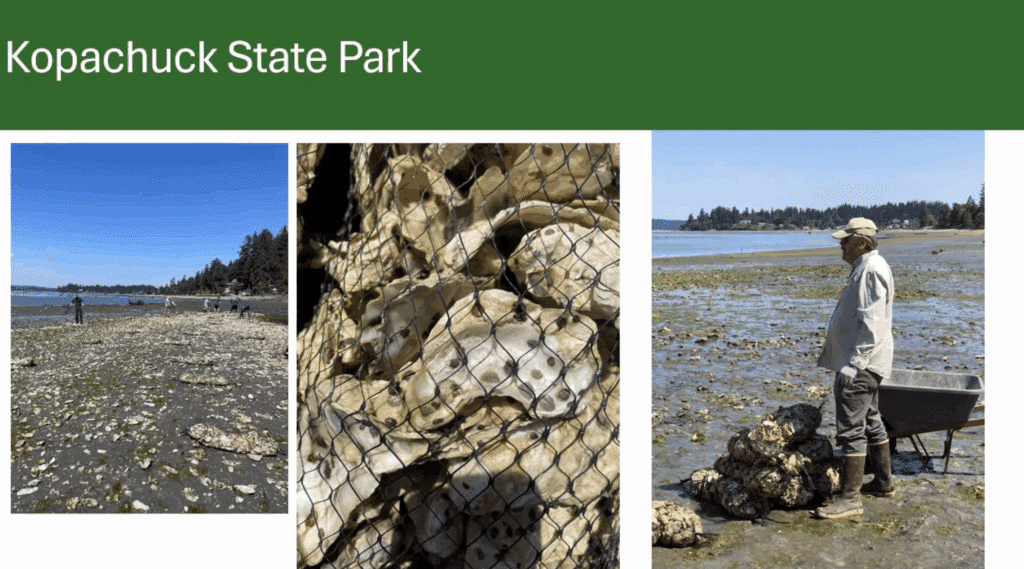

Up and down the peninsula, including at Gig Harbor’s Kopachuck State Park, Dudding and his teammates on the state Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Intertidal Shellfish Management Team work to “seed” Pacific oysters and Manila clams, as part of the state’s bivalve stock enhancement program.

Though the department has other teams that manage stock of other aquatic life that people farm and eat, Dudding and his team are solely responsible for these two specific shellfish species. Both are major aquaculture species and recreational harvest draws.

Pacific oysters, he explained, were intentionally introduced to Washington in the late 1800s or early 1900s. They originally hail from Japan. The state and tribal partners co-manage both these oysters and Manila clams.

An image from Jack Dudding’s presentation about shellfish management.

Seeding

The species grow fairly differently, he said. The teams “seed” the clams and oysters at different parks.

The teams seed an average of six beaches every year with Manila clams, spending about $60,000 to purchase four and a half million juveniles from Taylor Shellfish Farms for the endeavor. The little babies they strew throughout these beaches are just four microns big.

The teams receive baby clams in large buckets, Dudding said, and “we just Johnny Appleseed it around on the beach.”

“We go in on an incoming tide and we seed it along the water line,” he said. “As the tide comes in, it keeps the seed wet and gives the clams time to dig in before the crabs get to them. That’s a big aspect for seeding. We expect about a 25% survival to harvest size. So that’s as good as we think it’s gonna be. It’s really hard to evaluate on the back end.”

The teams seed Pacific Oysters at anywhere from one to seven beaches, depending on the year, Dudding said. Oyster babies are known as spats, and the teams beef up these beaches’ populations using 50-700 bags of seeded cultch, or a place for spats to grow.

In this case, the teams use oyster shells. Each bag contains 250 cultch, and each cultch has about 12 spats. The way the teams seed the clutches ensure that the spats grow into individual oysters, rather than one large cluster, Dudding explained.

“We do this because clusters have a way of digging in and staying on the beach. They’re kind of resistant to … prevailing winds or tides moving them around,” Dudding said of the spats, which cost about $28 to $30 per bag. The state primarily purchases them from the Rock Point Oyster Company.

New methods

For many years, the state contracted with the Jim Hayes, a now-81-year-old man from the Hood Canal Oyster Company both to purchase spats as a sort of middleman for the state, and to seed them. Hayes is retired, but Dudding explained his method of seeding oysters.

“He would go to the beaches at high tide and barge all the … seeded culture over, and this is how they would spread it around using hoes,” Dudding said, showing attendees a photo in his slideshow. “They would use the boat to drift over these enhancement beds and hose it off and kind of get a nice, even spread of seeded culture over the bed.”

But this practice has changed with the recent incursions of Japanese Oyster Drill and European Green Crabs, both invasive species who pose serious risks to the Pacific Northwest ecosystem.

Now, the teams seed oysters differently, Dudding said. The teams now hook and haul bags over mud and stack them on pallets to go through a process known as “beach hardening.”

During beach hardening, spats battle the elements and intertidal fluctuations. This helps them develop stronger abductor muscles. Oysters use abductor muscles to open and close their shells, and stronger abductor muscles mean that they will do better during exposure at low tide, when they may be out of the water.

Spats go through beach hardening anywhere from 60 — 90 days, Dudding said. If the teams exceed 90 days, oysters can grow too big for the mesh and become entangled. This makes it difficult to get them out of the bags, and the operations are already labor-intensive, as it is.

“We move everything out in wheelbarrows or by hand and stack it on pallets. This mostly keeps the shell out of the mud from suffocating the spat,” he said. “These are usually big operations. It requires a lot of people to get out.”

The teams also work with the Squaxin and Suquamish Tribes for additional seeding work for both Pacific Oysters and Manila Clams.

Invasive species

While Japanese Oyster Drills — a kind of invasive snail species — have been around for a long time, European Green Crabs are a fairly new threat, having moved through the Strait of Juan de Fuca into Puget Sound. The crab is now intruding further south into the Hood Canal and central Puget Sound. Both snail and crab pose a serious danger to aquatic life, including oysters and clams.

“Those are challenges and those are the reason we switched from using barge methods, where we beach hardened on a different site and brought them in,” Dudding said. Moving seed stocks from one exposed place to another could risk contamination with these invasive species.

The newer practice of bringing bags directly from hatchery settling tanks and placing them at beaches is safer, but also more labor-and logistics-intensive.

“You’re having to move a lot of people and a lot of heavy products to a beach,” Dudding said. “You have a finite number of tide days to work with. Beaches require very specific tides.”

Sustainable enhancement

The environmental traits of each beach also factor into the teams’ work. Any oysters seeded at Kopachuck State Park are exposed to quite a bit of “fetch,” or the distance wind travels over water. A large amount of fetch means large waves. Wind and waves regularly pound the oyster stock at Kopachuck.

“It doesn’t lock in quite as well there,” Dudding said of the spats’ ability to stay put under constant physical pressure of wind and wave, “but it has persisted over the last 30 years.”

The team also has to figure out how to balance cost and harvest pressure. For instance, he said, Penrose State Park has seen a lot of visitors recently. The teams have had to consider how to continue to make recreational harvest sustainable.

“We are doing this enhancement for the purpose of creating recreational opportunity, but it has to be sustainable,” Dudding said. “It has long-term ecological benefits as well. … This is a big team effort. It takes a lot of people to help.”