Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | Behind the Finds: Chuck Sharman

When Tonya Strickland and I stumbled onto a pile of disorganized old photographs in Josephine’s Mercantile in Port Orchard in February, it was not immediately apparent what a treasure trove that scrambled stack would turn out to be. Those pictures display much of the history of the Wolford and Persing families of South Tacoma, including the many years of Don and Doris Wolford in Cromwell on the Gig Harbor Peninsula. We have been telling their stories in the Gig Harbor Now series Behind the Finds:

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Behind the Finds | Every picture has a story

Behind the Finds | Georg, Brigida and John Wolford

Included in the stack of images were a few of people who appear to have been friends rather than relatives of the Wolfords or Persings. We initially decided not to try to follow the friends’ stories, as a few unrelated pictures are nowhere near as interesting as the hundred or so of the primary subjects.

After all, how much of a story can you get from one or two random snapshots? Is there any possibility of finding something even remotely interesting from a single photo?

Ohhhh, yeah.

Anchors aweigh

“Look — a picture of a sailor. I wonder if it’s World War 2?” I said to Tonya.

That’s how this particular photo adventure began.

An instinctive twist of the wrist to check the backside of the 5×7 print proved that it was indeed WW2. But the real prize was the sailor’s name, C. E. Sharman. That was something I could work with. It’s always encouraging when a last name isn’t painfully common.

Had the last name been Smith or Brown or Anderson, I wouldn’t even have tried to look him up. Maybe not even if his name had been Sherman. But how common can Sharman be? Not very.

So, how do you go about looking up a sailor from WW2 named C. E. Sharman?

Considering that his picture was found in the remnants of Jean Wolford Rohrs’ photo albums, it seemed reasonable to wonder if he was one of her high school friends from South Tacoma. A quick check of Tacoma newspapers from 1930 to 1940 showed that he was indeed a Lincoln High School graduate in 1940. It also revealed that his first name was Charles, though he more often used Chuck.

What that first step in the search didn’t turn up was this fair warning to anyone planning to look further into Chuck Sharman’s history: Hang onto your hat, Grammaw!

Charles Ernest Sharman

Chuck Sharman was born in Tacoma on July 1, 1922. An only child, he lived with his parents until around the time of their divorce. According to the 1940 Census, Chuck had lived with his grandmother, Lettie Sharman, in South Tacoma since at least 1935, which happened to be the year her husband (and Chuck’s grandfather) died. That means he spent his high school years in her house.

Chuck Sharman spent his high school years living with his grandmother in this house in South Tacoma. Photo by Greg Spadoni.

Like many high schoolers, Chuck had a best friend, Bob Mitchell, a dedicated car nut. The two would share a dramatic and unpredictable fate soon after high school.

Another bonanza

After working from the single photograph of Chuck in his Navy dress blues to rough out this column, I received an unexpected windfall of sorts. Heather Rennaker, the vendor of the Magpie + Raven section of Josephine’s Mercantile in Port Orchard, loaned Tonya and I even more photos from Jean Wolford Rohrs’ personal collection. Hundreds of them!

Among the stacks and bags were several of Chuck — and Bob — as teenagers. They, with a couple other friends, were in front of Jean Wolford’s house on South Oakes Street in Tacoma, and at an unidentified saltwater beach.

Chuck Sharman (left) and Bob Mitchell (in the car) in front of Jean Wolford’s house on Tacoma’s South Oakes Street. Photo provided by Heather Rennaker.

A suddenly camera-shy Chuck Sharman (left) and Bob Mitchell (right) on a blanket on a beach with Virg, another friend of Jean Wolford’s. Photo provided by Heather Rennaker.

It’s impossible to tell from those pictures that both Chuck and Bob were destined for unusually interesting lives, a development that came shockingly quick.

In 1940, after Chuck graduated from Lincoln High, he and Bob (who had dropped out of school) wanted to remain best friends, wherever they ended up. With war raging in Europe, sending dark clouds towards America, the two young men enlisted — together — in the U.S. Navy.

Uh-oh

When following the trail of Chuck Sharman through history, it was pretty easy to guess what was coming when I found that he and Bob were assigned to the battleship USS Arizona during the summer of 1940. Nearly every one of a certain age should know that the Arizona suffered the heaviest casualties during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Over 1,000 sailors are entombed in its hull to this day.

But Sharman and Mitchell are not among them. They both escaped that fate, for their orders changed shortly before they were to report to the Arizona. They instead joined the crew of another battleship, the USS California.

For those less familiar with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, the California also sank that morning on Battleship Row.

The next newspaper mention of Chuck Sharman was the announcement of his death, having been killed in action on December 7th, as was Bob Mitchell. Shipmates and best friends to the end.

Shown here in happier times as carefree 16 or 17-year-olds, in the upper photo Chuck is in front of Jean Wolford’s house on Tacoma’s South Oakes Street. In the lower photo Chuck and Bob are wrasslin’ on the beach. Both boys were reported killed in action at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, during the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941. Photos provided by Heather Rennaker.

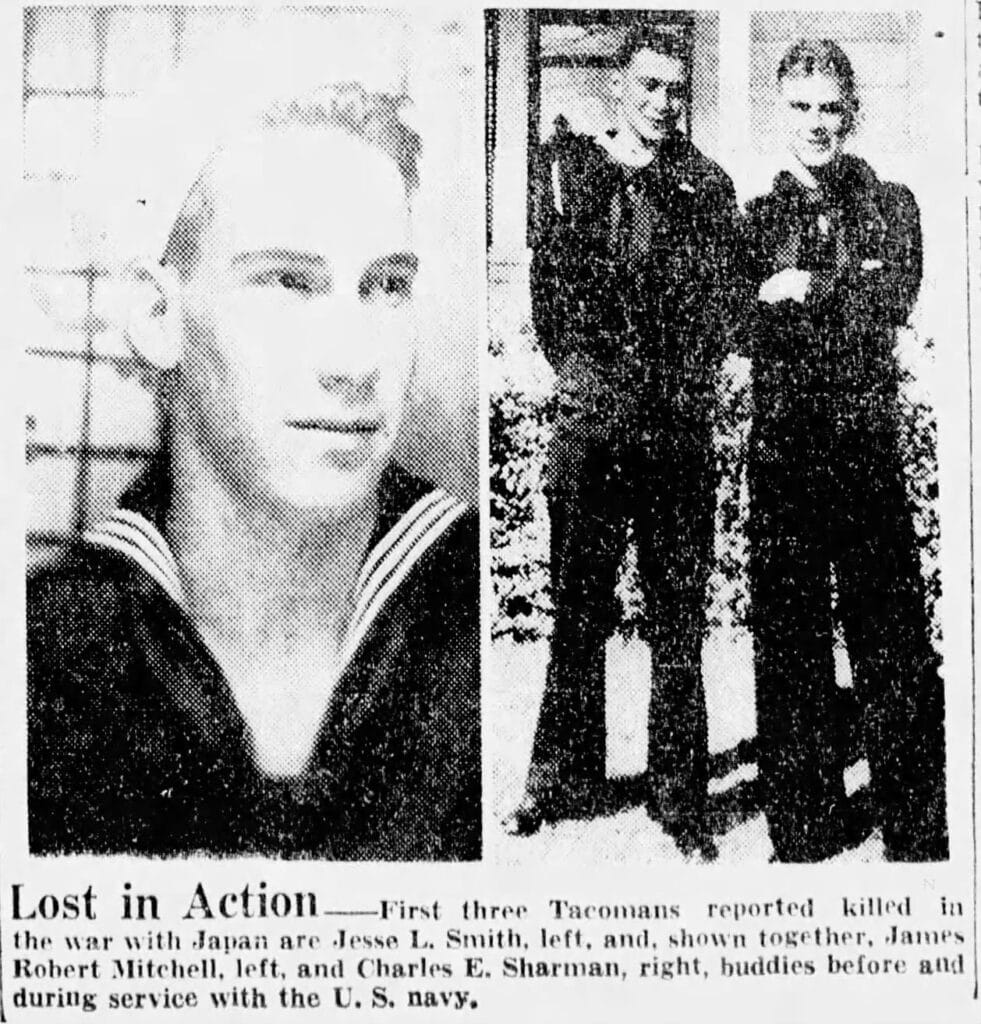

From the front page of The News Tribune, Thursday, December 18, 1941:

3 Tacoma Men Lost In Action

Relatives Here Learn of Supreme Sacrifice by Navy Men in New War

Three Tacoma young men, two of them former News Tribune carriers. James Robert Mitchell and Charles E. Sharman, each 19, and Jesse L. Smith, all of the U. S. navy, lost their lives in action, the government has informed relatives. “Bob” Mitchell and Charles Sharman are Lincoln high school graduates, were members of the Naval Reserve and entered active service as signalmen together more than a year ago and apparently met the same fate. Both were members of Asbury Methodist church and Mitchell was an Eagle Scout. “Lost in performance of duty,” the brief message told parents. Surviving James Robert Mitchell are his father, James Mitchell, 6401 South Montgomery Street, a brother, Edward, of Tacoma and two sisters. Mrs. Chester H. Kingshurg of Seattle and Mrs. Frank B. Wickens of Tacoma. His mother died in August and he came home on a month’s furlough. Charles E. Sharman is survived by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Sharman of 6843 South Warner Street and his grandmother, Mrs. L. M. Sharman of 6438 South Warner Street.

On page 1 of its December 18, 1941, issue, The News Tribune ran this pair of photos of three sailors from Tacoma who were reported killed in action on December 7th. Jesse Smith, a shipmate of the other two, was actually from Houston, Texas, but had recently married a Tacoma girl.

The families held memorial services for the two boys in Asbury Methodist Church at 5601 South Puget Sound Ave., and their spirits, if not their remains, were laid to rest.

The aftermath

There isn’t much more to say about two young men, not even out of their teens, who were killed in action on the first day of the United States’ participation in World War 2.

There was this, however, on January 6, 1942, also in The News Tribune:

Two more Tacoma boys in the navy, previously reported “lost in action” in the Pacific warfare, are alive and well. They are James Robert Mitchell … and Charles Sharman… The youths, former Lincoln High School students and both News Tribune carriers, were buddies here and in the navy. Dec. 17, the News Tribune announced relatives had received official word that the two were lost. Recently both families were notified officially that the first announcement was in error. Now both families have letters written by the boys and giving assurance they are all right. “I understand you have been worrying about us.” Sharman wrote. “Let us do the worrying.”

(The “two more Tacoma boys” were in addition to Jessie L. Smith, who was also mistakenly reported as killed in action.)

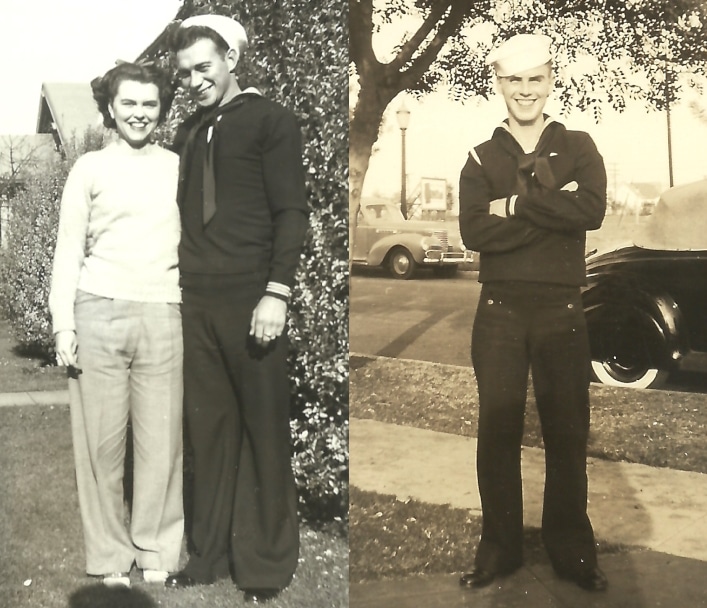

Jean Wolford, the original source of all the non-newspaper pictures in today’s column, is standing with Bob Mitchell on the left. On the right is Chuck Sharman. In spite of initial reports by the Navy, both boys survived the sinking of their ship during the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Photos provided by Heather Rennaker.

Not an isolated error

In the mass confusion that was the aftermath of the two waves of attacking Japanese warplanes, accurate casualty counts were simply not possible. A similar mistake was made with Gig Harbor’s William Edward Reeder. The December 19, 1941, Peninsula Gateway reported: “The regrettable news was received here last week, of the death of Wm. Edward Reeder, a Peninsula man, who was killed in action in the Pacific, since the outbreak of the war. Last October he was married, his wife being the former Gladys DeWalt. The bereaved have the sympathy of the entire community.”

Unlike with Sharman and Mitchell, the error was corrected before the end of the month. The December 29, 1941, News Tribune ran this bit of good news: “A letter from Hawaii was a joyous Christmas present, and assured Mrs. William Reeder a happy New Year. … This week she got a letter from him, dated Dec. 18.”

Killed in action again

In another error, this one by The News Tribune itself, seven months after announcing they had survived the attack at Pearl Harbor, the newspaper once again listed Sharman and Mitchell as having been killed in the war. A front page article naming Pierce County’s war dead up to July, 1942, failed to take Chuck and Bob off the list.

… and again

In March, 1943, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was compiling a list of Pierce County dead and missing during the ongoing war. The names would make up an honor roll that would be inscribed on the walls of the Liberty Center, a temporary portable war memorial, at 9th and Broadway in downtown Tacoma. Once again Sharman and Mitchell were mistakenly included.

Surviving the rest of the war

The 1995 book USS California (BB 44) by author Pat Martin, edited by Erik Parrent, and compiled by Turner Publishing, has preserved a brief account of Chuck Sharman’s wartime history, in his own words:

My buddy, Bob Mitchell, and I had some good luck in the summer of 1940 and again in December of 1941. A week or two before we were to report aboard ship for duty in July of 1940, our orders were changed from the USS Arizona to the USS California. We became signalmen on the USS California, CBB-445. On the morning of December 7, 1941, I was relieving the watch on the signal bridge shortly before 8:00 a.m. I heard the engines of several planes, looked up, and saw three planes wing over and start to dive just forward of our bow. Even as I saw their bombs fall, I thought they must be our own planes. Not until the explosions of the patrol plane hangers on Ford Island, and I saw the red meatballs on the wings, did I realize that the planes were Japanese aircraft. My buddy and I made it through the attack. However, our families in Tacoma, Washington, were notified that we had been killed- in-action and they proceeded to have memorial services for us at our church and at the VFW, where a year or two before we had played in the marching band. In a few weeks’ time they learned we were alive after all, and removed our names from the Memorial Pylon in town. About a week after the Japanese attack, word was passed that most of the USS California signalmen were to be transferred to four heavy cruisers. They were the USS Vincennes, the USS Chicago, the USS Astoria, and the USS Portland. We were allowed our choice of ship. Mitch and I decided we wanted to be on a ship named for a city close to our home town, so the Chicago and Vicennes were immediately eliminated. That left the Portland and Astoria. Both were cities in Oregon, but we thought that Portland was closer to Tacoma than Astoria was, so we went aboard the Portland, the only one of the four cruisers to survive the war. Only after joining her crew did we discover she was named for Portland, Maine, not Portland, Oregon! Following the battle of Midway, Bob Mitchell was transferred to the USS Atlanta, where he was wounded when she was sunk off Guadalcanal in November, 1942. Later he served on the destroyer USS Halford, finishing the war as chief quartermaster. ln January, 1943, I left the Portland and went to the USS Crescent City, an APA [Attack Transport]. Several months later I was on the Lunga Point Tower on Guadalcanal. During that time the Halford came out from the United States and took station off Lunga Point, making runs north through the Solomon Islands. I had not seen Mitch for many months and finagled my way on board for a good visit of several days. Later in the year of 1943, I went back to the United States and was part of the commissioning crew of the [destroyer] USS Van Valkenburgh. When the war ended, I was teaching NAN Signaling School in Pearl Harbor where it all began on that unforgettable day aboard the California.

Clandestine communications

After Bob Mitchell was transferred to a different ship, the two best friends remained in touch until one or the other left the Pacific Theater. In a Gig Harbor Now and Then exclusive, it can finally be revealed that while they were serving on different ships, both as signalmen, they would on occasion send a code word from ship to ship to find out if the other was on board and on duty. I have been entrusted by Bob Mitchell’s son Tom to blab to the world what the code word is, and to do so, I’ll use Tom’s own words: “They were on different ships later on but since they were signalmen they could sometimes communicate. I was told they would signal the phrase “panamabananaman” as a way to make contact.”

(In a billion-to-one coincidence, panamabananaman just happens to be my password for … OK, so maybe it’s not. But it certainly could be in the future.)

After the war

The two best friends managed to find each other again at the end of the war, and after their discharges from the Navy, traveled back to Tacoma together.

The News Tribune, Thursday, November 1, 1945, page 23:

Together At Lincoln, in War, And Now at U.

A parallel that began at Lincoln high school before the war continued a true course this week when James Robert Mitchell and Charles E. Sharman enrolled at the University of Washington. The former Lincoln classmates joined the navy together and were reported killed aboard the battleship California when Pearl Harbor was bombed in 1941.

Then came various assignments in the Pacific finally discharges at Camp Shoemaker, Calif. They came home on the same train, Sharman as a signalman first class and Mitchell as a chief quartermaster.

When the pair came back to Tacoma in 1945, Chuck already had a wife, and a son he named Mitchell.

For his part, Bob Mitchell, the high school dropout, made up for lost time and eventually earned a Ph.D in educational psychology.

Great luck doesn’t always last

Chuck Sharman made it through WW2 without harm, but civilian life would have some difficult surprises for him. A few years after having a third son, Dave, in 1960, he and his wife divorced.

Far more consequential, at least from a life-and-death perspective, was a dark day in May, 1971, when he was living in Olympia. A speeding, out-of-control, chronic drug-abusing driver crossed the centerline and hit Chuck’s car head on. Mitchell was slightly injured, Dave seriously so, and Chuck entered St. Peter Hospital in critical condition.

(The same driver, again out of control, killed a passenger in his car when he wrecked in 1974.)

Chuck ultimately pulled through, and his life went on to have yet another unlikely twist.

Joking around

Chuck Sharman loved to draw, and while on the USS California, he was known as the ship’s cartoonist. To him, art was not a mere hobby, but a calling. After attending art school in Mexico, he sold his first comic to the Saturday Evening Post in 1949. Work for such national magazines as Collier’s, Argosy, True, Look, Esquire, and others followed.

In the late 1970s he went back to sea — in a manner of speaking — when he moved into a 33-foot cabin cruiser he moored at Friday Harbor in the San Juan Islands. Around the same time, he started a new project that became quite successful.

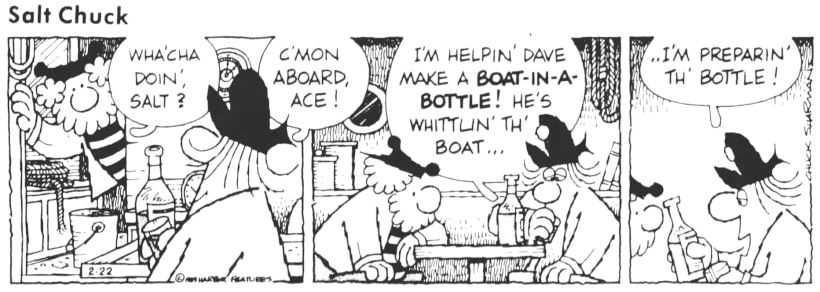

Many older Gig Harbor residents will no doubt recall his daily comic strip, Salt Chuck, which ran in The Tacoma News Tribune from 1979 to 1986. It continued on in a variety of other U.S. newspapers until he gave it up in 1991. It had also run in Australia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

Chuck Sharman said he didn’t name his comic strip after himself. “Chuck,” he explained, is an Indian word for water. This is the February 22, 1983, installment of Salt Chuck.

And the twists keep on coming

In the middle of Salt Chuck’s run, Sharman was sidelined for months with what turned out to be a successful battle with throat cancer. He resumed writing the strip and continued with it for several more years. Somewhere along the way he managed to beat lung cancer as well.

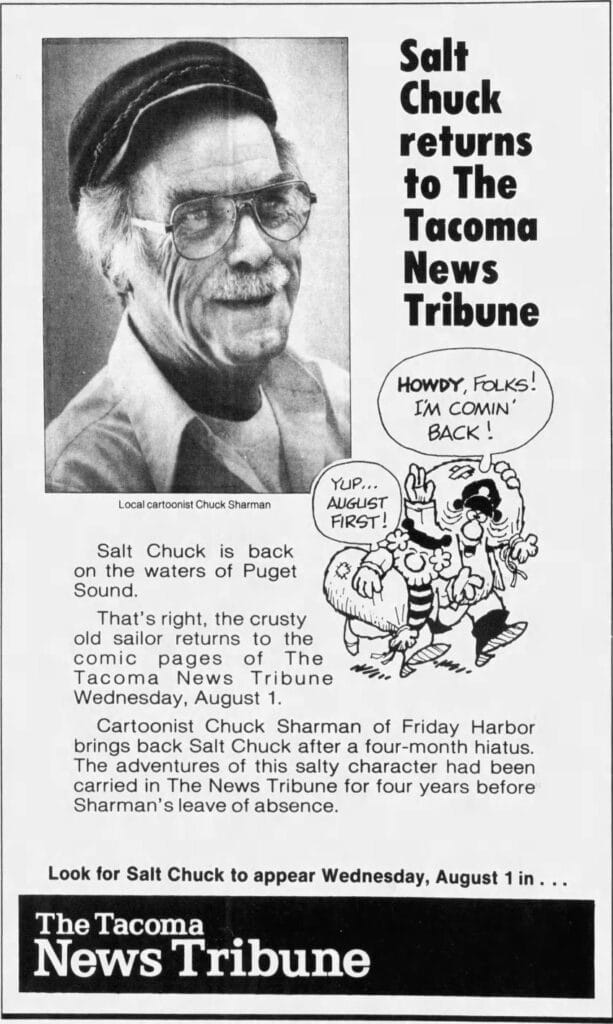

On July 31, 1984, The Tacoma News Tribune ran a big announcement of the return of the comic strip Salt Chuck, after Chuck Sharman’s four-month hiatus for cancer treatments.

A photographic portal to unexpected results

A single photo of one sailor from over 80 years ago, found in a stack of pictures of two South Tacoma families he was not a member of, preserved just enough information (his name) to allow for the discovery of the 20-year-old’s very surprising life.

Chuck Sharman barely escaped the fate of the doomed USS Arizona, survived the sinking of the USS California, was declared dead and given a funeral, became a professional artist, was nearly killed in a car crash, evolved into a syndicated newspaper cartoonist (with his hometown paper running his strip), and beat cancer twice.

Not many people have done any of those things.

Chuck also kept in touch with his best friend, Bob Mitchell, for the rest of his life. Bob lived in several foreign countries during the course of his career, but returned to Washington in the 1980s, where the friendship continued.

After an amazing life, Chuck died in Tacoma in 1995 of pneumonia. Bob passed away in 2003. Not bad at all for two South Tacoma kids who were officially declared dead in December, 1941.

Photo provided by Heather Rennaker.

Note: My thanks to Tom Mitchell of Seattle for identifying Bob Mitchell in Jean Wolford’s photos and providing other useful information.

Next time

Finally, it’s time to return to questions of local history … I think, anyway. If nothing goes sideways between now and then, on May 19 we will have two questions about the Gig Harbor commercial fishing fleet.

As I warned last time, the questions themselves might not be all that interesting, but the answers sure will be, on June 2.

That statement draws a question of its own: If the answers are far more interesting than the questions, why not just skip the questions and go right to the answers?

Because I’ve already written both columns.

Besides, the one with the questions has two interesting photos. They’re highly unusual local pictures that have nothing to do with the Gig Harbor fishing fleet, but are so unique they deserve to be seen. In fact, they might contain cryptic messages from beyond the grave. I don’t think they do, but that won’t stop certain others from claiming they’re proof of the dead trying to communicate with the living.

OooooOOOOOooooo!

— Greg Spadoni, May 5, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.