Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The answer to this burning question about a ferry

Gig Harbor Now and Then’s question last time concerned the first ferry boat to serve on the Gig Harbor-Tacoma run, beginning in 1919. After only a few months, the City of Tacoma was taken out of service while a roof was constructed over its car deck.

Arts & Entertainment Sponsor

Arts & Entertainment stories are made possible in part by the Gig Harbor Film Festival, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Why did the car ferry City of Tacoma need a roof over its car deck?

Answer: To prevent fire damage to the automobiles it carried.

The City of Tacoma was a steam-powered ferry boat, fueled by cordwood. Many, if not a majority, of the automobiles at that time had tops made of canvas or other fabrics, not steel. Burning embers blown out the ferry’s stack were too often landing on the fabric car roofs and burning holes in them.

As this graphic representation clearly shows, an automobile roof on fire — especially on a ferry — is a frightening thing. The damage could run into some serious money. Replacing this car’s roof today would cost $1.19 plus tax. Photo by Greg Spadoni

There is no explanation of why a spark arrestor wasn’t fitted to the ferry’s stack. Spark arrestors were commonly used by a wide variety of wood and coal-fired boilers of the day. They were not a novelty or an unproven method to keep firebox embers in check.

A reasonable question is: Why didn’t the boat already have a roof over the car deck when Pierce County purchased it? The ferry was originally named City of Vancouver, having been used to cross the Columbia River between Vancouver and Portland from 1909 to 1917. Didn’t it burn holes in automobile tops during those first eight years? Or were Columbia River people simply more tolerant of such easily preventable damage?

What was the ridiculous reason Pierce County’s first auto ferry wasn’t put on the Gig Harbor–Tacoma run until two years after it was purchased for that purpose?

Answer: There was no dock in Tacoma capable of allowing cars to drive on to or off of a ferry boat.

In 1917, when the Pierce County commissioners decided to purchase the county’s first ferry boat, they had a ferry slip added to the new concrete dock being built at the head of the bay in Gig Harbor. But without a dock on the Tacoma side that could accommodate the loading of cars, ferry service was not possible.

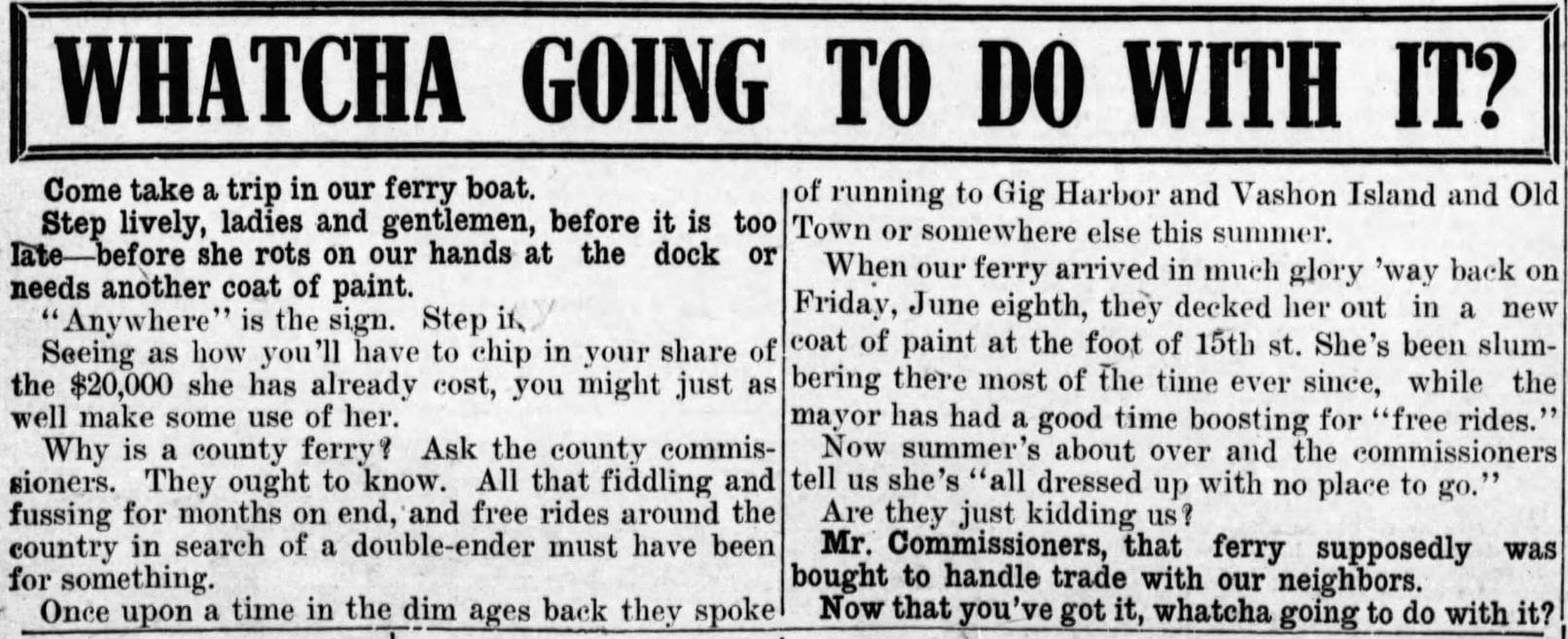

On August 24, 1917, an editorial in The Tacoma Times publicly asked the Pierce County commissioners what they were intending to do with a ferry that had no place to go.

The United States entered World War 1 in the same year, which further complicated Pierce County’s plans to initiate ferry service to Gig Harbor. Because of the war, priorities were changed, and the City of Tacoma spent the next year and a half carrying commuters to and from the shipyards on the Tacoma tide flats. During all that time, it used steamer docks to load and unload the passengers, as a ferry slip was not constructed in Tacoma until after the war was over.

Why did the ferry City of Tacoma come to Gig Harbor during the two years it wasn’t carrying cars?

Answer: On occasion it was chartered to carry passengers for specific events, but the primary reason it came to Gig Harbor during those years was to load cordwood for fuel.

Gig Harbor Now and Then editorial opinion

One of the several goals of Gig Harbor Now and Then is to correct errors of local history. In a rare expansion, this week we go global.

There is an error in the modern English alphabet, the 26 letters of which are used in many places around the world, including on the Gig Harbor Now website. The mistake was made a long time ago, which makes it history. And with the English alphabet being used frequently on the Gig Harbor Peninsula, the subject is also local.

We’re all familiar with the letter u. We’re equally familiar with the letter w. And while the official name of the latter, spelled out, is double-u, no one seems to notice — or care — that w is not really a double u.

W can sometimes be a double u in handwriting, but mostly in lower case. In typewriting, however, w is never a double u. In fact, in both lower and upper cases, it’s always a double v.

The common description of something as “u-shaped” refers specifically to the rounded bottom of the letter u, whether in upper or lower case.

The typewritten w has what sort of contour on the bottom? A v shape. Two of them, in fact, which makes the letter a double v, not a double u.

Does the letter on the right look like a double version of the letter on the left? Of course not. It looks like a double version of the letter in the middle.

What could be simpler or more obvious?

That’s not the only letter of the alphabet with a questionable name. Another example is m. Technically, it’s a double n no matter what form it’s written in. In lower case, both m and n have rounded tops, and in upper case, sharp tops. Yet m has its own name, entirely separate from the letter n, while w masquerades as a double version of a previous letter, u, when in fact it’s a double v.

And what about C? If w can be named after another letter in the alphabet, why isn’t C named “incomplete O”? Or F “two-thirds E”? P should obviously be named “one-legged R.”

C is nothing more than an incomplete O; F is two-thirds of an E, and P is a one-legged R.

So, what’s the solution to the incorrect naming of the letter w? The first step is to identify the source of the problem, which we have already done.

Kids today are first taught the alphabet in or before preschool, by teachers, parents, computer games, or educational television programs. They learn that the letter w is called double-u, rather than what it really is, double–v. And in spite of double-u making no sense, they believe it.

The problem, then, lies squarely with the child-like gullibility of pre-schoolers. If they would stop being so willfully naïve and express a sharpened sense of intellectual skepticism instead of simply going along to get along, maybe the errors and inconsistencies of alphabet names wouldn’t be tolerated generation after generation.

Advanced societies progress and thrive only when everyone participates to the best of their abilities. Unless and until the post-toddler set begins to effectively employ a higher standard of critical thinking, the letter double-v will continue to masquerade as double-u, and the progression of society will remain proportionately stunted.

Harsh, I know, but it needed to be said.

A bonus issue

As a twice-a-month column, Gig Harbor Now and Then is not scheduled to run a new piece next week, but we will, providing I don’t get fired for this week’s hard-hitting editorial. Next Monday is April Fools’ Day, and as today’s column clearly demonstrates, if anyone at this publication is perfectly suited for it, it’s me.

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the Museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.