Business Community Environment

Kensington Gardens’ experts testify during third day of hearing

Though the day was decidedly shorter, lasting only about four hours, the third day of the hearing for local elder care business Kensington Gardens’ application for a single-family residence subdivision platting was no less informational than the first two hearing days.

Kelly and Mark Watson own the business, whose two main buildings are styled after a European villa and an English manor. The luxury living campus on a large tract of land on Olson Drive NW has been the focus of some controversy in rural Gig Harbor. Erika and Dana Zimmerman, who live across from the business, have appealed a recent subplat permit.

The state Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) also recently issued Kensington Gardens a cease-and-desist letter and a civil fine in July. DSHS stated that the business was operating an unlicensed adult family home. The Watsons appealed the decision in early August. The appeal puts a stay on the cease-and-desist order.

If the hearing examiner in the case approves the new subplat permit application, the business would have the green light to build a total of six more buildings on the property.

During the first two days of the hearing, on Aug. 11 and Aug. 12, several speakers covered a number of topics the Zimmermans highlighted in their appeal of the project. These speakers included expert witnesses for the appellants, the appellants themselves, and Kelly Watson, who spoke at the very end of the hearing’s second day.

Expert witnesses for the Watsons testified on the third day of the hearing. Watson also spoke again towards the end of the hearing’s third day, along with a neighbor and three Kensington residents.

The Hawksworth Villa at Kensington Gardens, as seen from the road on Aug. 17, 2025. Photo by Carolyn Bick. © Carolyn Bick

Wetlands

On the hearing’s second day, Dr. Sarah Spear Cooke, testifying as an expert witness on behalf of the Zimmermans, highlighted a number of issues with the Watsons’ environmental assessment. In that testimony, she said the assessment was done at the wrong time of year — in December, outside the growing season. She also pointed out that the Watsons’ assessment lacked third-party review. Spear Cooke has not visited the property to do an assessment.

Spear Cooke said the environmental assessment should be done in the growing season to properly assess the area with respect to wetland vegetation, soils, and hydrology. This appears to line up with the recommendations in the state’s and the Army Corps of Engineers’ wetland delineation manuals. With regard to hydrophytic vegetation — “water-loving” plants found in a wetland — the regional supplement to the Corps’ manual specifically states that, “[t]o the extent possible, the hydrophytic vegetation decision should be based on the plant community that is normally present during the wet portion of the growing season in a normal rainfall year.”

Spear Cook taught the Corps what would eventually become its delineation manual, and helped the state develop its wetlands ratings.

She also said the wetlands assessor the Watsons hired misclassified the northern wetland as a slope wetland. A stream runs through it, as indicated on the Pierce County Geographic Information System (GIS). It should therefore be classified as a riverine wetland, rather than a slope wetland, Spear Cooke said. A riverine wetland is one that rivers or streams frequently flood.

Riverine vs. slope

If classified as a riverine wetland, the buffers around it would need to be wider. Wetland buffers reduce harm to the wildlife in a wetland, act as habitat for several species, moderate the effects of stormwater runoff, and filter toxic substances.

This is why time of year matters when collecting data for a wetland delineation, Spear Cooke said. If data isn’t collected when the water is fully running, then the wetland classification can be lower, and, among other issues, the buffers won’t be high enough.

“At least some of the hydrology for this wetland is contributed by a river,” Spear Cooke said of the northern wetland. “It is not just a slope.”

She also said that the Watsons’ wetlands consultant did not log that a seasonal stream runs through the southern wetland on the property, because of the time of year the consultant did her assessment. However, she agreed with the consultant’s assessment of the southern wetland as a depressional one.

Timing of the assessment

Barbara Best, who did the wetlands assessment for the Watsons, said the manual does not include a specific requirement for the assessment to be done at any particular time of year. She said she has visited the property about 10 or 15 times since 2005.

“It’s a recommendation that comes forward and there’s just cautionary language to be sure that you’re considering that some of your indicators may not be exactly what they would be during the growing season,” Best said.

Best has 35 years of experience as a wetlands consultant and runs Harbor Environmental Review Services, which she started in 1997. She has also served on planning panels and helped develop some of the language of those panels. She is on the list of qualified specialists to work in Pierce County.

In the hearing, Best confirmed with Reuben Schutz, one of the Watsons’ two lawyers, that doing an assessment during the growing season is ideal, but that doing an assessment at other times is acceptable.

“There’s not always that flexibility to be able to do it at different times, although I was on this site many times other than the December date,” Best said. She didn’t offer further explanation as to why she did not do the assessment at a different time, but estimated she had been on-site three or four times since the assessment.

Best also stood by her slope wetland classification for the northern wetland. Also called a seep, a slope wetland can often be found on farm fields, forests and meadows. They occur where groundwater makes its way to the surface.

Best said that, in her opinion, the wetland doesn’t qualify as a riverine wetland, based on criteria found in the delineation manual and her observations in December.

“One of the criteria for the riverine wetland is the riverine wetland is associated with valleys and flood zones and we don’t have flood zone … mapped on site,” Best said, referring also to the county’s GIS. “A riverine wetland lies along the edges of a river and there needs to be overbank flooding at least every two years. So, you’ll see some evidence of that, which I never have identified on site.”

Seasonal stream

Of the southern wetland’s stream, Spear Cooke said that “it’s stated by everybody, including the neighbor, that it’s a seasonal stream,” and that Best missed the seasonal stream and stream corridor, because of the time of year she went out. Spear Cooke pointed to aerial views of the property that showed a stream corridor — “it’s one continuous vegetated band.”

Spear Cooke said neighbors have also reported the stream occasionally flows from south to north during major storm events, even though there is a topographic break between the north and south area. This means that, normally, the water in the north drains north, and the water in the south drains south.

Overall, however, Spear Cooke agreed with Best’s assessment that the southern wetland is a depressional wetland.

Best also said that, having been on the property, the under-canopy vegetation is sparse.

However, during her testimony Spear Cook also said that this vegetation assessment was done at the wrong time of year — again, in the winter, outside the growing season — and that this meant Sissons may have missed several plants that die back in the winter. The species they did find, she told the hearing examiner, “were just a tiny subset of what should have been, what would be present.”

“If you’re not good at plant identification in the winter, once the leaves are gone on the trees, it’s just bare twigs unless it’s a conifer,” Spear Cook said. “So there could have been way more species in the woody species than they identified, and then all the herbs in the lower canopy have died back. … They only found the two things that didn’t die back, which were ferns.”

‘In full force’

Best said that when one does an assessment during a time of year when certain indicators won’t be out “in full force … you need to look at the evidence of the presence of those indicators or the lack of those indicators.”

“And so for plants, you’re looking at bark on trees, you’re looking at buds, you’re looking at thorns on bushes,” Best said. “Sometimes I might snap something off and smell it and see whether or not it meets that recognition of that particular species. You’re looking at a vegetation that has died for herbaceous species that might be laying on the ground that you’re able to identify.”

Best said that she had enough experience to properly identify all the vegetation present in the area, even though she did the assessment in December. She said that Spear Cooke’s opinion was formed from overhead views, rather than views on the ground.

“I looked back at what [Spear Cooke] had commented about related to the overall cover, and as you get down underneath that canopy into that wetland, you find that the vegetation is pretty sparse underneath there,” Best said. “A good portion of that canopy comes from the buffers that are just at the edge of the wetland and have some mature trees present. So, yeah, I did look at it again, looked at it really carefully, and have looked at it since first reading it in 2005, a number of times.”

County biologist’s view

County biologist Steve Sissons also testified that he agreed with Best’s findings, stating that there is “a distinct break between the upland vegetation and the hydrophytic vegetation. So it was pretty much a no brainer.”

He also said that “there really isn’t any wrong time to go out and do a delineation. I mean, there’s preferred times, certainly in the growing season, early part of the growing season.”

Sissons verified Best’s work in December 2021, about a year after Best went out.

He also said that because the existing buildings are classified for use as single-family residences — rather than commercial, civic, industrial or another more intensive use classification — the buffer height of a slope wetland classification is adequate.

However, when Audrey Clungeon, the lawyer for the Zimmermans’ environmental appeal, asked Sissons about land use code, Sissons indicated that he had not reviewed the land use code in as much detail as Clungeon was trying to ask him about.

Sissons also said that it is not usual for Pierce County to conduct a third-party review of an environmental assessment.

“At one time when we were super, super busy — I don’t know, five, six years ago — we had third-party review, but no, we do not do that on a regular basis,” Sissons said.

The hearing examiner denied Clungeon’s request to recall Spear Cooke as a rebuttal witness, because it would add another day to the already lengthy hearing, and denied her request to ask Spear Cooke to submit a rebuttal in writing, because there would be no opportunity to cross-examine her.

Septic

In his expert testimony for the appellants, professional engineer Timothy Gross pointed out that the Watsons lacked key information required in their SEPA checklist, and that other areas had inconsistent information.

For instance, the Watsons state “not applicable,” when asked about waste material discharged into the ground from septic systems.

“My understanding, based on the plat the primary plat submittal, is that the applicant is intending to deal with the sanitary drainage from these properties using a septic drain field — and the SEPA checklist specifically asks questions about effluent from septic drain fields and septic systems and they said not applicable,” Gross said. “So they’re inconsistent with each other.”

Gross also said that there was not enough information to determine whether the existing septic system can handle more load, and pointed out that the septic inspector who issued reports for the existing structures did not properly calculate how much a system can handle. Per state regulations, load is determined by the number of bedrooms.

In the course of answering Watson lawyer Bill Lynn’s questions, George Waun, the county health department’s water resources supervisor, emphasized the preliminary nature of the platting plans. He said that the as-submitted plans are typical of the kind the health department approves.

Missing information

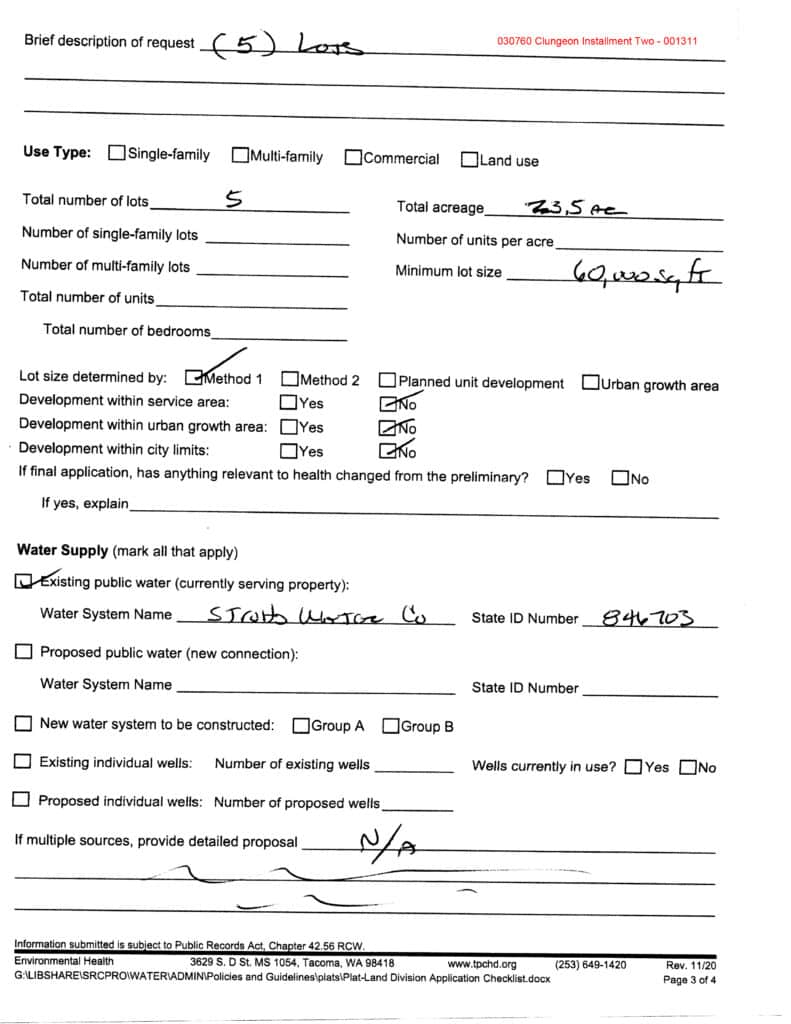

As Gross pointed out on the hearing’s second day, the as-submitted plans lack several pieces of information. For instance, even though the Watsons are applying for a single-family residence permit, they left that area unchecked. It also does not state the number of bedrooms.

Kensington Gardens’ plat/land division application leaves blank the number of bedrooms anticipated.

Waun also said that the health department issues approvals with “basic” information about whether soils on the property can handle septic drainage. He confirmed to Lynn that the soils on site appeared to have the capacity to function as a drainfield.

Waun also confirmed that septic waste flow and volume must be accounted for in the design plans, and that this is based on the number of bedrooms in a residential structure. In the course of cross-examination, Waun later said that the department does not look at the number of bedrooms during a preliminary platting process. He said that the department looks at the number of bedrooms during a feasibility study.

When Lynn asked whether more soil information is required by the time the final design is submitted, Waun said that “at the time of development of each lot, we do have the option to require additional test pits for review,” but the code only requires a minimum of one test hole per lot, during the preliminary phase.

“Depending on the proposal, we may require that there be two in primary and two placed in an area of potential reserve,” Waun said. He did not indicate whether this was done for the Kensington complex.

No bearing on decision

When Clungeon cross-examined him, Waun said that different land use types dictate drainage requirements. Clungeon pointed out that the Watsons did not check off a use type on their permit application form, and asked, “If they had indicated the use type, does that impact your analysis?”

“It wouldn’t at this stage of the process,” Waun said. He did not offer further explanation, and Clungeon did not follow up to ask why.

When Clungeon asked whether Waun’s analysis about whether a septic permit is allowed for the site, if the application were a proposal for a residential care facility, Waun said, “Not from a health or site and soil condition standpoint.”

“The only consideration is that as a part of a development application, the sewage needs to be treated to a residential waste strength standard, which can be done regardless of use on the property,” Waun said, in response to Clungeon’s question about whether there are certain land use types where septic is not allowed.

Clungeon also indicated on the form that the Watsons had not listed the number of bedrooms in the buildings. Waun confirmed that “[i]t’s information that’s asked for on the application, but it doesn’t have any bearing on my decision.”

Building department information

He later confirmed that, if bedroom information is later added, it is possible that such information could restrict or limit development, but that the health department goes off information provided by the building department, rather than blueprints. This means that the health department uses a certificate of occupancy — the number of bedrooms an owner lists — rather than blueprints that show rooms that could, by state definition, be considered bedrooms.

These are areas like offices, such as the rooms in the existing Carriage House at Kensington Gardens. The Carriage House is an accessory dwelling unit that previously housed elders. Kensington staff offices are there now.

Waun confirmed that a certificate of occupancy can reflect fewer bedrooms than what the state would consider a bedroom. Clungeon excluded areas like offices, however, that could be considered bedrooms. She confirmed with Waun that, just going off the certificate of occupancy, which reflects 12 bedrooms, state law would dictate a minimum septic capacity of 1,440 gallons.

Waun also said that the soils present can dictate treatment level and size of the drainfield, or whatever disposal method a development will use.

He said the health department had not analyzed any of this.

“All you looked at is are there soils that could treat an unknown amount of waste?” Clungeon asked.

“Correct,” Waun confirmed.

Waun said that, as part of the site and soil evaluation, the health department determines where there are layers of soil in the ground that prevent sewage from flowing into the ground — called “restrictive layers” — or where there is groundwater in the soil. This, he said, establishes where the required vertical space between where the sewage would enter the ground and where the sewage could enter groundwater should be located.

Waun said that the department determined this on the Kensington property, and found that there is about 30 inches of soil. This means that there will need to be a certain level of sewage treatment for the drainfield.

But while groundwater is taken into account — in this case, the perched, or high, water table on the property — Waun said that the health department does not account for septic proximity to wetlands or other critical areas. It also does not take into account the presence of an aquifer recharge area. He said that this is the purview of the county’s Planning and Public Works Department.

Public comment

Kelly Watson again appeared before the hearing examiner to give public comment, in addition to the letter she had submitted on behalf of her husband, Mark Watson.

Watson told the hearing examiner that she had told the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) that they would not be using adult family home licenses anymore, because of the model of care they wanted to pursue. She said they would prefer only to be licensed by the state’s Department of Health (DOH) as an in-home care agency, which they are.

She also said that state law allows the Watsons to run the complex this way, due to state law that says counties may not restrict the number of unrelated people who live in one household or dwelling unit.

Watson also said that, at Kensington Gardens, there “isn’t abuse or neglect … [of which] adult family homes have quite a bit.” She said that they are trying to provide a care model that ensures elders are well cared-for.

“We’re trying to be the leaders and say, look, this can easily be done anywhere,” Watson said. “It’s residential. The laws are in place. We can show you how to do it.”

A neighbor, Paul Donion, also testified on behalf of the Watsons. He said that he has not heard other people in the neighborhood criticizing the Watsons or Kensington Gardens, and that Kensington Gardens has been a “tremendous” neighbor.

A married couple and one other person who live at Kensington Gardens also positively testified to the quality of their living conditions.

The hearing examiner set a tentative due date for closing arguments of Sept. 19, with a decision tentatively set for early October.