Community

Census: Growth slowed considerably outside the city of Gig Harbor

Recently released 2020 U.S. Census numbers tell a tale of two Gig Harbors: a city that experienced a decade of frothy development and population growth, and another area calling itself Gig Harbor — the unincorporated lands of the Gig Harbor Peninsula — that appears to have followed a quite different trajectory.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Census numbers show population growth on the peninsula outside the city actually — are you ready for it? — slowing down over the past 10 years. Between 2010 and 2020, the unincorporated part of the peninsula gained 2,851 residents, an increase of 6.9 percent. That’s less than half the 14.3 percent growth rate experienced during the prior decade.

The 94-lot Chelsea Park subdivision couldn’t be built now off of Hunt Street. It was already in the pipeline when rules were changed. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

These numbers might surprise longtime residents who have lived through the many growth controversies on the peninsula, and inspire those hoping to stem the tide of suburban sprawl. The lower growth rate in unincorporated areas even suggests that the state’s Growth Management Act (GMA), passed in 1990, is achieving its goal: preserving the natural environment and facilitating the provision of services to residents by channeling growth into urban areas, while taking population pressure off areas farther out and allowing them to stay rural.

But comparing these census population measurements between decades is not entirely apples-to-apples. For one thing, the city boundaries have grown, taking up faster-growing areas that were previously unincorporated. This has the effect of increasing the city’s growth numbers while tamping down the growth rate measured outside the city.

The corner of 38th and Hunt streets was cleared in August for the 13-home Wimbledon development. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

The numbers also mask the fact that the GMA’s rural preservation benefits are spread unevenly. While outlying districts such as Arletta, Artondale, Cromwell and Rosedale have enjoyed relief from large-scale development, closer-in areas are subject, even now, to the kind of forestland-to-subdivision transformation that has ignited growth wars over the decades.

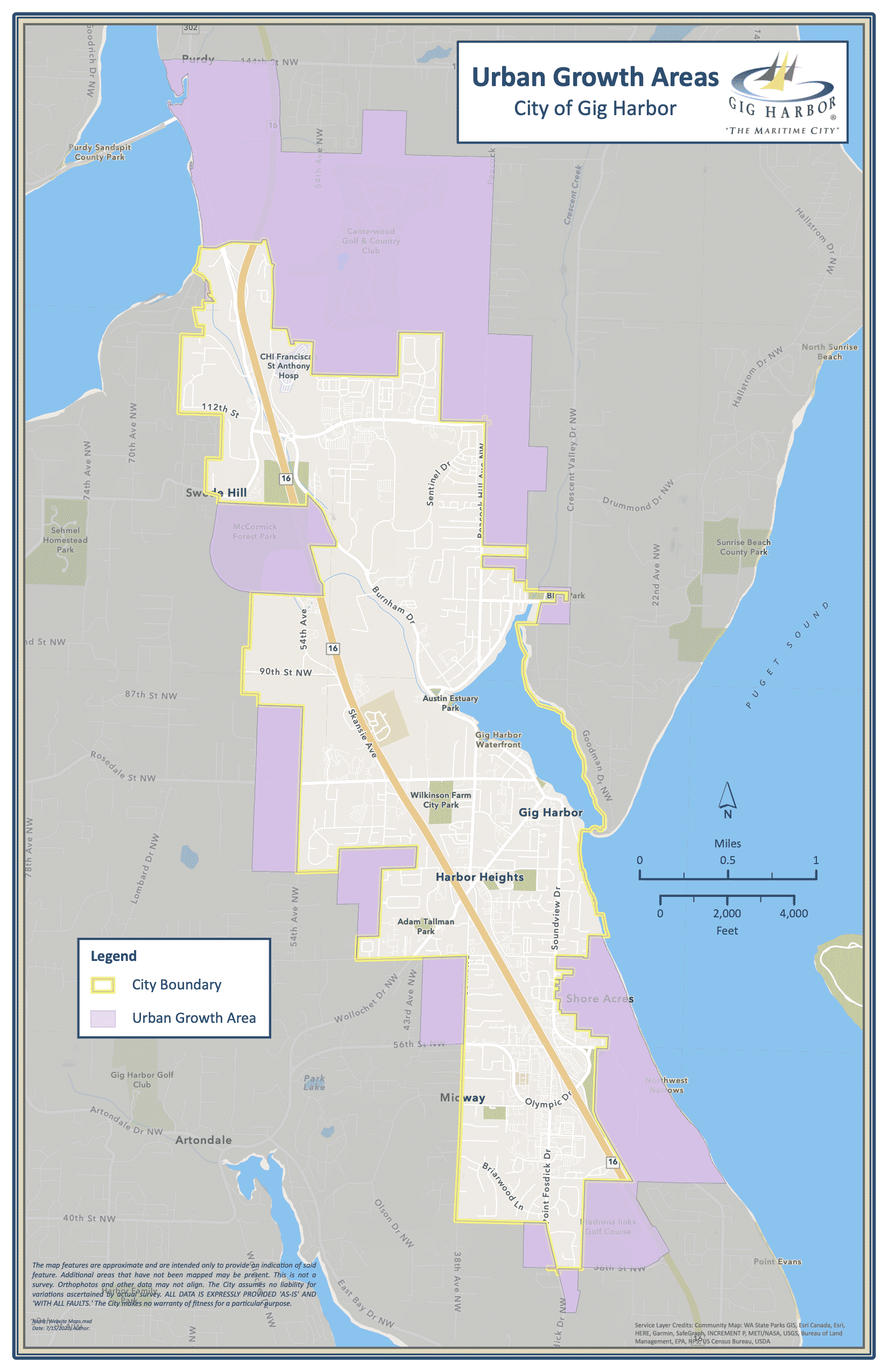

Not all unincorporated areas are equal in terms of what’s allowed under the act. Some land close to the city is in the area designated as the city’s urban growth area (UGA), which is designed under the Growth Management Act to experience urbanization at a much faster clip than outlying areas. A UGA also constitutes the unincorporated area that is available for a city to annex.

When zoning regulations stemming from the GMA went into effect on Jan. 1, 1995, the urban density subdivision activity that had been allowed throughout the peninsula and Fox Island was replaced with much lower rural densities, with the exception of the city of Gig Harbor UGA. The most common zoning in the rural area is one home per 10 acres, or two homes if half the property is left in open space. In a limited area, one home per 5 acres is allowed. In contrast, within the UGA, residential zoning allows a maximum four or six homes per net developable acre, with higher densities in the Purdy commercial area.

Hundreds of homes were built across Peacock Hill Avenue from the old Woodcrest development, and now 16 more are planned nearby in Harbor Run. Ed Friedrich / Gig Harbor Now

Projects in the rural areas that were already going through permitting at the time of the 1995 downzone were allowed to go forward, resulting in some neighborhoods sprouting up that would not be allowed if they were proposed today. Chelsea Park, a 94-lot subdivision off Hunt Street NW near the Artondale Cemetery, is one example. But today, most such “vested” projects have either been completed or ceased moving forward.

Closer in, within the UGA part of the unincorporated peninsula, it’s still possible to find bulldozers clearing out woodlands in anticipation of new subdivisions. One such infill project is Wimbledon, west of the city off 38th Street NW, where ground is being prepared for 13 single-family home lots on 4.38 acres across from Tacoma Community College’s Gig Harbor campus. Two other projects in the works, closer to the city’s high-growth hot spot Gig Harbor North, are Burnham Ridge, with 20 lots on 7.03 acres between Burnham Drive NW and Highway 16, across the freeway from McCormick Forest Park; and Harbor Run, with 16 lots on 5 acres east of Peacock Hill Avenue NW.

The idea that growth has slowed significantly over the past decade is hard to fathom if you’re in parts of unincorporated Pierce County bordering Harbor Run, residents say. Terra Jacobson and her family moved to Woodcrest, an older development next to the proposed Harbor Run site, more than six years ago. She had lived in Gig Harbor in her teens and graduated from Gig Harbor High School. When she moved to Woodcrest, trees surrounded her house and neighborhood, and much of the land off of Peacock Hill Avenue NW was forested as well.

Within six months of moving there, “all the trees were gone” on the other side of Peacock Hill Avenue NW in order to make way for Harbor Hill, the largest of the developments at Gig Harbor North. Between Harbor Hill and a few other developments, some 400 homes have been added within a mile of Jacobson’s house, she estimated, with the heaviest concentration right across Peacock Hill Avenue NW from Woodcrest.

“If they keep having this growth, I’m not sure how long Peacock Hill Avenue is going to run with just one lane each way,” Jacobson said.

At Woodcrest and elsewhere near the Harbor Run site, residents are calling on county planning officials to address their concerns about the project. Major worries include whether the loss of forest cover at Harbor Run will make trees on adjoining properties more vulnerable to windstorms, and stormwater and the potential for flooding a nearby wetland.