Community Environment

With bear sightings on the rise, locals learn to live with the wild

The vibration that shook a Gig Harbor house on a recent Wednesday evening was so intense, the people inside thought it might be an earthquake.

Then a neighbor called, warning of a black bear in the neighborhood. The critter scaled the neighbor’s tall fence with surprising speed.

Another tremor rattled the house. An enormous, fur-covered bear bolted through the yard. It was about 6 p.m.

One scared bear

“He was scared,” said the resident, Ren, who asked that her full name not be used. “He didn’t even stop to eat berries or garbage. When he landed (off the fence), the whole ground shook.”

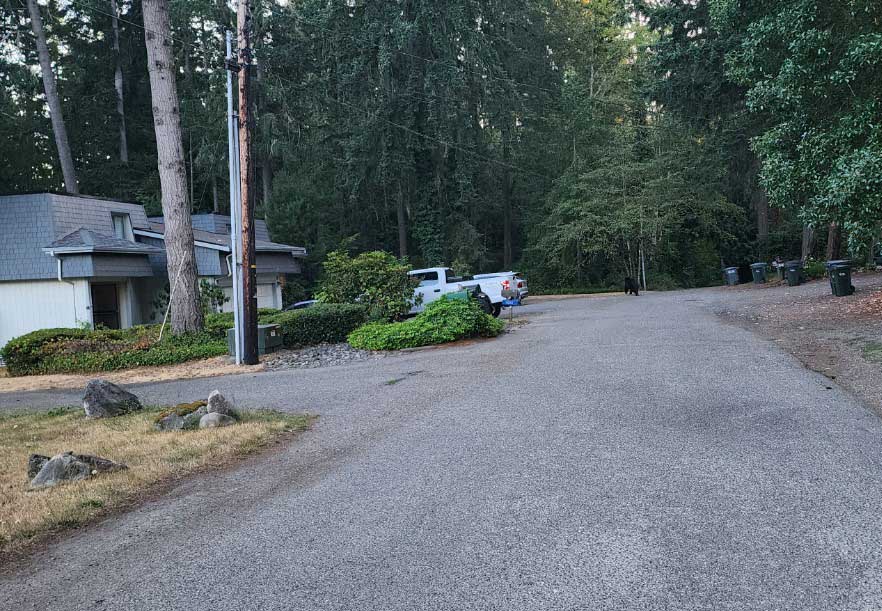

Ren last saw the bear sprinting along the residential street before vanishing into the forested canopy that borders her neighborhood near Gig Harbor High School.

It left behind a broken fence panel and an unsettled resident. “This is one of the biggest bears I’ve ever seen,” Ren said.

A lifelong hiker well-versed in nature and wildlife, Ren found herself perplexed. Why was she seeing a confused bear in a residential neighborhood?

A black bear retreats from Ren’s Gig Harbor neighborhood.

More bear, or just more cameras?

“Anecdotally, we are receiving more calls about wildlife sightings,” said Jennifer Becar, communications manager for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). “Bear, backyard deer, we are getting quite a few calls of that nature.”

The increase in calls, however, does not necessarily correlate to an increase in wildlife population, Becar said. “We suspect some of the increase in sightings is because there (are) more eyes on them.”

That means doorbell security cameras, for example, a home monitoring system that continues to grow in popularity. More than 1 in 4 Americans use a security system to protect their home and property, according to The State of Safety in America 2023, a report prepared by a home security organization called SafeWise.

Whether tech-assisted or by old-school eyeballs, bear sightings have been reported in various local locations, including Point Fosdick, Arletta, Trinity Ridge, Fox Island and even Gig Harbor neighborhoods adjacent to Highway 16.

A bear exploring a back yard in a Gig Harbor neighborhood in August 2023.

Humans encroaching on wildlife habitat

Coyotes have been observed in Wilkinson Park during daylight hours and their calls can be heard in and around Gig Harbor. Evidence of bear presence, such as scat, has been recorded in populated areas like Peacock Hill.

According to the WDFW, “as human populations encroach on bear habitat, people and bears have greater chances of encountering each other.” An estimated 20,000 black bears live in Washington state, not only in forested coastal and dry woodland habitats, but also in suburban areas.

According to the 2020 Census, Gig Harbor’s population soared by 69% growth over the span of a decade. That well exceeds the statewide growth rate of 14.6%.

One of the greatest threats to all species of bear is habitat loss. Less area for bears to hunt means a greater likelihood of human contact, sometimes resulting in human-wildlife conflict. Habitat loss brings wildlife, like bears and cougars, closer to the suburbs.

Timelapse video shows the growth of development in the Gig Harbor area since 1984.

Good eating

According to the WDFW, the primary cause of conflicts is people not acting responsibly. Each year, WDFW’s phone lines are inundated with reports of issues stemming from humans.

The reports often involve bears getting into trash cans, pet food and bird feeders. In some cases, campers don’t adequately secure their food while sleeping in bear country.

“Our human-supplied food offers so many more calories,” said Dr. Lindsay Welfelt, a WDFW specialist in bears and other wildlife. This allows bear to grow bigger.

Welfelt just completed retrieving data in a black bear monitoring project for the WDFW. Her most recent research site was west of Hoodsport in Mason County.

For 40 days at various sites throughout Washington state, Welfelt and her team retrieve data to determine black bear density with the goal of updating the estimate of black bears in the state. Wildlife density estimates help guide population management and provide important science exploring the relationship between habitat characteristics and a species’ abundance.

Gathering data

Gathering data for research is quite an odorous task. At each location, black bears are enticed into a hair trap enclosed by barbed wire, allured by a mixture composed of rotten cow blood and fish oil. “It is gross. No way to get around it, it is gross,” Welfelt said.

The bears catch a whiff of the enticing scent and maneuver through the loosely spaced barbed wire. As they traverse the wire, fragments of their fur get snagged. WDFW carefully extracts the fur and documents it for DNA analysis.

The goal is to look at trends, like “which areas have more bears and less bears, and associate that with habitat features,” she said. “If we know that bears have less population with more roads and people,” that is a pattern. Welfelt and her colleagues document that habitat feature.

Human-supplied food

The average-sized female bear weighs 140 to 150 pounds. The average male is 230 pounds.

But “with access to human-supplied foods, those weights can drastically change. They can essentially double,” Welfelt said.

When it comes to food, Welfelt said, it’s about time management for bears.

“If a bear were to eat 1 pound of huckleberries they’d get 160 calories, and it might take an hour. Whereas a pound of birdseed might take 10 minutes. They get 1,700 calories,” she said. “Human-supplied foods provide so many more calories and are densely located. Naturally (sourced) foods are spread all over.”

So why wouldn’t they go to one person’s backyard to get everything they need? “That’s why it’s so important not to provide that. If it’s there, they’ll take advantage of it,” Says Welfelt.

Black bears possess a remarkable ability to detect food through their sharp sense of smell. Scientists estimate that their sense of smell is seven times more potent than that of a domestic dog. Their vision and hearing also surpass that of humans.

A bear spotted in Grandview Park in Gig Harbor in June.

‘Patchwork habitats’

WDFW studies areas that are representative of habitats throughout the state, then draws inferences from these locations. Welfelt and her team studied the North Bend/Snoqualmie area, which bears the closest resemblance to Gig Harbor.

“In patchwork habitats, a mix of forest and housing — that can really facilitate bear use in that area. It provides habitat and it has access to human-provided foods,” she said.

The team attached GPS collars to a bear within the North Bend/Snoqualmie region. The findings revealed that a single bear can produce numerous reports. While monitoring two young bears, it became evident that they lacked a clear sense of direction. Older bears exhibited more proficient navigation through urban environments.

“A lot of times those calls tend to be younger bears when they leave their mom,” Welfelt said. Bears usually separate from their mother at about 1 1/2 years old. “Yearling bears don’t really know what they’re doing,”

They also witnessed the effect of displacement. In one location an entire habitat area “was wiped out the following year. You can imagine, you’re not going to move, you’re going to try and live in that area,”

The bears equipped with GPS devices supplied data to assess survival and reproduction rates, and hibernation patterns. The findings will provide the WSDW with the necessary information to update their management of black bears.

(1/2)

Black Bears are more common in our area than you may think. They generally mind their own business.Monday morning, we had 1 report of a bear near Grandview Forest Park. We have not had any additional sightings since. The bear has likely moved to another area. pic.twitter.com/2ZWjTHd2pO

— Gig Harbor Police (@GigHarborPolice) June 14, 2023

How weather comes into play

Weather and changing climate also impacts habitats studies. For example, areas in the Eastern Cascades experienced a spike in reports of bears getting into food.

“We had a huge failure in our natural foods because of the drought,” Welfelt said. When natural foods are not available, bears are even more likely to seek out those calorie-rich people foods.

The overarching message from Welfelt and WDFW: “Don’t have those attractants on your property. Don’t give them a reason to be near your house, or near your property. That’s the biggest thing.”

Preventing contact with bears

The WDFW suggests the following strategies around your property to prevent conflicts:

-

- Don’t feed bears. Over 90 percent of human-bear conflicts result from bears being conditioned to associate food with humans. A wild bear can become permanently food-conditioned after only one handout experience. The unintended reality is that these bears will likely die, perhaps killed by someone protecting their property or by a wildlife manager called to remove a potentially dangerous bear.

- Manage your garbage. If you have a pickup service, put garbage out shortly before the truck arrives, not the night before. If you’re leaving several days before pickup, haul your garbage to a dump. If necessary, frequently haul your garbage to a dumpsite to avoid odors. Keep garbage cans with tight-fitting lids in a shed, garage or fenced area. Spray garbage cans and dumpsters regularly with disinfectants to reduce odors. Keep fish parts and meat waste in your freezer until they can be disposed of properly. If bears are common in your area, consider investing in a commercially available bear-proof garbage container. Ask your local waste management company if bear-proof garbage containers are available or if individually purchased containers are acceptable and compatible with their equipment.

For more information about how to prevent human-bear conflict around your home and small livestock, as well as bear safety tips while hiking, camping, or hunting visit bearwise.org.

Bear Attacks

Although black bear attacks are rare, anytime you are in bear habitat you should know what to do should an encounter occur. If you come in close contact with a bear:

-

- Stop, remain calm, and assess the situation. If the bear seems unaware of you, move away quietly when it’s not looking in your direction. Continue to observe the animal as you retreat, watching for changes in its behavior.

- If a bear walks toward you, identify yourself as a human by standing up, waving your hands above your head, and talking to the bear in a low voice. If you have bear spray, get it out of the holster and remove the safety.

- If you cannot safely move away from the bear or the bear continues toward you, scare it away by clapping your hands, stomping your feet and yelling. If you are in a group, stand shoulder-to shoulder and raise and wave your arms to appear intimidating. The more it persists, the more aggressive your response should be. If you have bear spray, use it.

- Do not run from the bear. Bears can run up to 35 mph and running may trigger an attack. Climbing a tree is generally not recommended, as black bears are adept climbers and may follow you.

In the unlikely event a black bear attacks, fight back aggressively using your hands, feet, legs, and any object you can reach. Aim for the eyes or spray bear spray into the bear’s face.

More information

For more information about living with bears in Washington, see the following WDFW handouts: