Community

Chapin Day | What’s in a name? For the Shenandoah, it’s up in the air

How did the name of an East Coast river valley end up on the bow of West Coast purse seiner fishing boat?

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

Good question.

I asked it almost two years ago when I signed on as a Harbor History Museum docent.

“Most likely,” museum staffers would intone, “the boat’s original owner, Pasco Dorotich, named it after a United States Navy dirigible that impressed him during its visit to Northwest skies in 1924 while his as yet-unnamed boat was under construction here at the Skansie shipyard.” Or words to that effect.

Hmmm. “Most likely …”

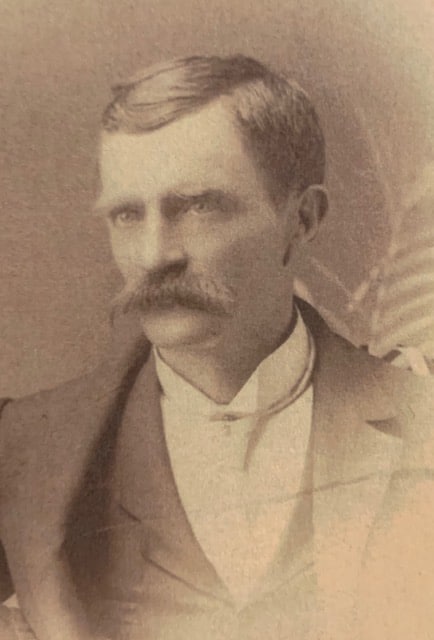

Pasco Dorotich

‘It’s a good bet’

Not what could be called a high standard of proof for history research, but a believable and somewhat charming story. I went with it.

Even museum director Stephanie Lile seemed to express a fondness for that narrative in a 2021 essay.

“It’s a good bet,” she wrote, ”that the mighty airship had been an inspiration” before conceding a few paragraphs later, “… we’ll never know what truly motivated Pasco Dorotich to name his boat.” (To read Lile’s essay, “The Mystery of the Name Shenandoah,” click here.)

For those of you who not familiar with the term docent, here’s how I explain my role to museum visitors: “You guests ask me a question and I say, ‘I docent know (pause for appreciative chuckle), but I’ll try to find out.’ ”

For me, the “finding out” can be more challenging and painful than waiting for the oft-omitted chuckle.

A few days back, inspired by the impending April 26 grand opening of the museum’s new Maritime Gallery, showcasing “Shenandoah,” I felt a need to shore up my knowledge about the origin of its name. I always strive to be a more decent docent.

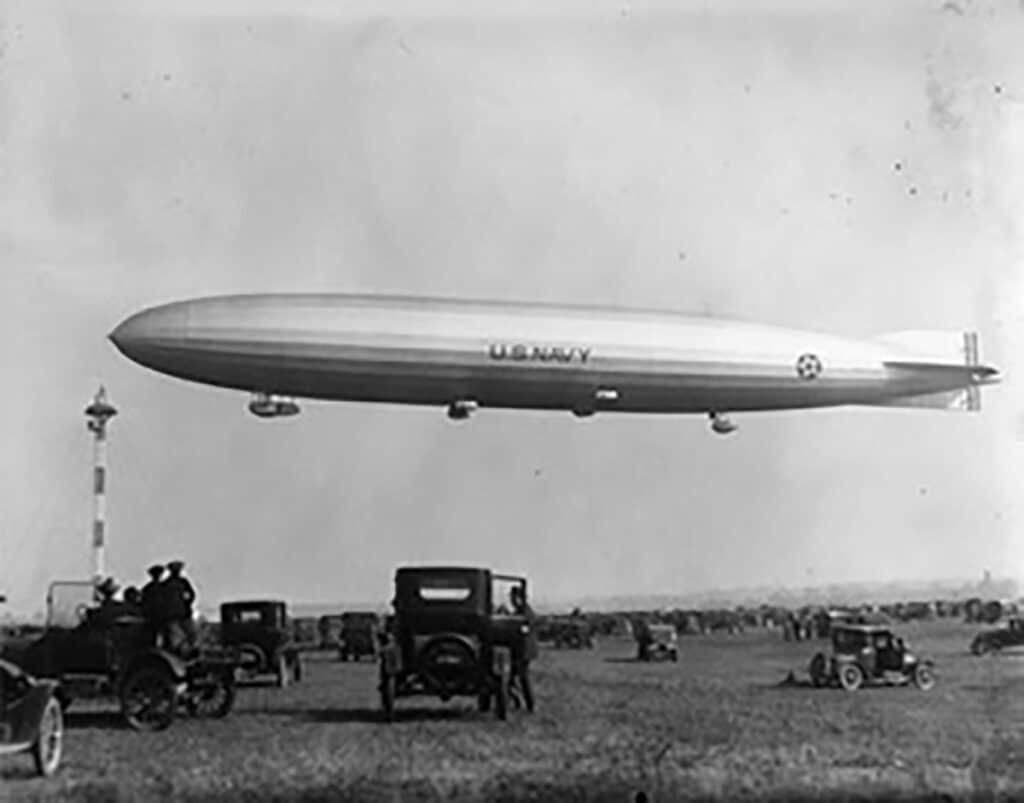

The Navy’s dirigible Shenandoah at Camp Lewis in Tacoma in 1924. Courtesy Northwest Room at the Tacoma Public Library, Image 3184.jpg

Plausible and probable

I turned, as I often do, to someone most likely to know about Gig Harbor history — and often most likely to be right— Jean Hannah, the museum’s Collections Specialist.

I found her, as usual, busy at her computer in her closed door, windowless, climate controlled office, a crammed cave of files, shelving, boxed history and artifacts towering all around her.

“What solid evidence do we have — documents, oral histories, whatever — that Dorotich named his boat for the dirigible?” I asked.

“None.” Jean can be charmingly blunt.

She went on to explain that the story evolved over time, made plausible by its probability.

Hmmm. “Most likely…” plus …”a good bet” in fancier English.

Now I was as hooked as a long-liner’s salmon. “Shenandoah”! Maybe it wasn’t the dirigible after all. I wanted to be sure.

A valley of undetermined length

My search began with the word shenandoah. So-called authoritative sources assured me that it was an attempt by English speakers to pronounce an Algonquin word or sounds meaning “great plains” or “spruce stream” or the name of a Susquehannock chief or an Oneida chief or an Iroquois chief or an Iroquoian phrase for “beautiful daughter of the stars” or “daughter of the stars.” Alternatively, maybe it was all or some of those.

I began to wish that these authoritative sources could get their act together. They similarly assured me separately that the Shenandoah Valley is either 140 or 200 or some other number of miles long. Seems to me that that one could be cleared up with a measuring tape.

Undaunted by these initial confusing forays into history research, I kept at it, still baffled by how the name Shenandoah transited a continent. Then, thanks to Director Lile’s essay and a Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum article, I refreshed my near nonexistent memory about Marion Bartlett Thurber Denby.

You remember her, don’t you? She married Edwin Denby in 1911. Surely you recall him: Secretary of the Navy in the Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge administrations, forced to resign his post in 1924 for his role in the Teapot Dome Scandal. You are summarily forgiven if you are a bit foggy on that scandal and those folks.

For our purposes today, you only need to know that on October 10, 1923, Edwin’s wife Marion had the honor of christening his Navy’s newest ship — its first rigid airship — a dirigible.

She named it after the Virginia valley where she was raised: Yup. Shenandoah.

This Shenandoah, now the anchor of Harbor History Museum’s soon-to-open Maritime Gallery, was probably named in honor of the other Shenandoah.

The dirigible

From its christening at Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, N.J., until its tragic demise in Ohio less than two years later, “Shenandoah” was a sight to behold.

She — boats and aircraft rarely get to pick their own pronouns — hovered over, dwarfed, and awed the estimated 5,000 spectators gathered inside a cavernous hangar for the christening ceremony.

Buoyed by more than 2 million cubic feet of scarce and costly helium, the silent Shenandoah floated aloft like some great, silvery, large-tailed fish, finned by six 300 horsepower Packard aircraft engines and a control cabin, all dangling on struts beneath the behemoth.

Proponents noted that she was the first dirigible inflated with relatively stable helium rather than with hydrogen, a cheaper, more abundant, more buoyant, but dangerously explosive gas.

She measured 80 feet in diameter and 680 feet long. That’s 40 feet longer than two end-to-end football fields complete with end zones and roughly three times as long as the largest Goodyear “blimp” in use today.

Goodyear corporate advertising executives were not the only folks recognizing the public’s awestruck reaction and PR value of giant aircraft lifting their logos into the sky. The nation’s generals and admirals noticed too.

In the wake of the first World War, the top brass were fighting the indifference of a Charleston-ing, distracted, Roaring ’20s public. Armed forces leadership sought ways to focus attention on their efforts to keep the nation militarily strong and — of course — taxpayer dollars flowing their way.

The Blue Angels of the 1920s

One strategy: Reinforce and encourage the public fascination with the flashy feats of those magnificent men and their new-fangled flying machines. The Army Air Corps held the distinct competitive advantage of having airfields scattered throughout the country from which to showcase its aviators and aircraft.

The Navy had to face the fact that it is tough to show off a fleet’s prowess in states lacking deep-water coastlines.

Ah … but a giant dirigible warship capable of long-range flight at speeds nearing 70 miles an hour could wow the citizenry above landlocked cities, towns and farmlands while proudly carrying the Navy flag.

A year after its christening, Shenandoah embarked from its Lakehurst homeport on a 19-day roundtrip transcontinental flight. In preparation for that voyage, planners had three mooring masts constructed — one in Fort Worth, Texas, one in San Diego and one at Camp Lewis in Tacoma (later known as Fort Lewis and today as Joint Base Lewis-McChord).

The Navy billed the trip as needed training for in-flight and ground crews. Other powerful motives: Publicity and inspiration of the sort provided in more recent decades by the Navy’s Blue Angels.

Slicing through an ocean of air Shenandoah stirred a coast-to-coast wave of patriotism and pride. Accounts describe Americans scrambling to get within eyeshot as she sped overhead. At her three (four counting Lakehurst) ports of call, throngs gathered to gawk and exclaim as she flew over or lay aloft at anchor on mooring masts.

Cruising around the Sound

Reports say that, upon her arrival in Tacoma in mid-October 1924, a technical delay in mooring freed “Shenandoah” to do a lap or so around Puget Sound, giving uncounted thousands of folks in Seattle and Bremerton areas inspiring views of this German-inspired, American-built marvel. Newspapers estimated that 10,000 spectators flocked to Camp Lewis after her eventual landing.

So, if you would like, go ahead and assume that Pasco, his son John, and his son-in-law Nick Bez, all outdoors men by profession, were among those dazzled. Seems a harmless supposition. After my tentative and ongoing trip along history lane, I have reached a firm conclusion.

Hmmm. Most likely…

Then, based on my general understanding that fishermen were a superstitious lot, I came up with another question for Collections Specialist Hannah.

Harbor History Museum Collections Specialist Jean Hannah aboard Shenandoah, the largest artifact in her care.

One year after its visit to Tacoma and just months after fishing vessel “Shenandoah” was launched in Gig Harbor, the dirigible broke apart and crashed during a thunderstorm in Ohio. Fourteen of the 43 crewmen aboard died.

“Do we have any evidence whatsoever that Dorotich gave any thought to re-naming his boat after the crash?

“None,” came her familiar reply.

Hmmm. Just hmmm.

Chapin Day

Chapin Day, certifiably not a certified historian, is an occasional volunteer contributor to Gig Harbor Now and a occasional volunteer docent at Gig Harbor Museum. Nothing in this column should be regarded as originating from or endorsed by either organization.