Arts & Entertainment Community

Gig Harbor Now and Then | The best-known Gig Harbor fishing boat worker

As Gig Harbor’s second major industry, behind only logging, the town’s commercial fishing boats have had probably thousands of workers over the last 150+ years. The majority likely worked on the boats to earn a living, but quite a number used the money to further other pursuits. Many deck hands fished to finance their educations. For example, Leon Spadoni fished with George Ancich for eight years to put himself through college and medical school. Rick McCabe fished one year with George Ancich and six with Vincent Skansi to put himself through college and dental school.

Community Sponsor

Community stories are made possible in part by Peninsula Light Co, a proud sponsor of Gig Harbor Now.

A select number of the commercial fishermen and women became very well known in Gig Harbor, especially boat captains, and some developed strong reputations throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Bringing to mind the idea of that high level of familiarity should — at least for the purposes of this column — lead to wondering who might be the best known of all the people who ever worked on Gig Harbor commercial fishing boats.

The popularity of a person can peak and fade. Sometimes people who are well known during one part of their lives tend towards the obscure later in life or after death. So, before it becomes the question of the week, we’ll break the curiosity down into two parts: who was the best known during their time on a boat, and who is the best known today.

- Of all the men and women who worked on Gig Harbor commercial fishing boats, from 1868 to the present day, who was the best known during their time on a boat?

- Of all the women and men who worked on Gig Harbor commercial fishing boats, from 1868 to the present day, who is the best known today?

Those, then, are the questions of the week. They are definitely difficult. Both answers have interesting twists to them, but be aware that one or both of the answers we’re looking for may or may not have been a fisherman or fisherwoman. Mechanics, boat builders, electricians, painters, and other professionals worked on commercial fishing boats in Gig Harbor too.

Also stipulated is that the name or names in question worked on a boat or boats while it/they were under way, as well as at dockside.

Ahh, the plot thickens!

In a further attempt to keep readers from feeling mislead, I’ll offer a broad hint: you don’t have to know anything about the Gig Harbor fishing fleet to get the right answers. That means anyone can figure them out.

I’ll even give another hint, one so specific that it’ll all but give one of the answers away: As a child, the best known woman or man today who ever worked on a Gig Harbor commercial fishing boat played the part of The Wind in their elementary school’s production of the play Rumpelstiltskin.

Gave it away

Oh, for crying out loud, now I’ve all but printed the answer! The only way it could be easier is if I blurted it out directly.

With that almost dead-giveaway hint, let’s calculate the new odds of getting the right answer. With an average bi-weekly readership of about 12, at least eight of you should come up with the right answer within minutes, if not seconds.

Yes, just a few lines ago I said that both questions “are definitely difficult.” But that was before I softened up and all but gave one away with that second, layup hint. Now, who could possibly NOT get the right answer?

I don’t know what I was thinking. I work, and I work, and I work to come up with interesting questions that have interesting answers, and then I go and give this one away. If anyone can’t figure out at least one of the answers, that’s on you (every third reader), not me.

But if it will make you feel any better — every third reader — after I post the answers in two weeks, if you didn’t get either one right, feel free to come to the Harbor History Museum on the following Wednesday, and I’ll write the correct answers on your forehead with a ballpoint pen. Your choice of color.

I’ll even write it backwards so you can read it by looking in a mirror.

Yes, I know, that’s above and beyond the call of a local history column, but that just shows I’m willing to go the extra mile to try to help Gig Harbor Now and Then reach that elusive two dozen readership goal. Man, we’ve got a long way to go!

Not quite old business

As a small addendum to Tonya Strickland’s current installment of the Behind the Finds series, the story of the elder Wolfords coming to Washington from the Midwest, I have an observation concerning the current residents of their house in South Tacoma. For my comments to make any sense (if that’s even possible), Tonya’s story really should be read first.

I say that with full awareness that 98% of readers don’t click on links. It’s just a more polite way of saying in advance, “I TOLD YOU my comments on Tonya’s story wouldn’t make any sense unless you click on the link, but did you? Nooo.”

At least the other 2% will not be confused.

Here’s what I have to add to Tonya’s Behind the Finds story this week:

As with old photos, the stories of the people you meet in real life can sometimes be wonderfully surprising.

Anthony Hunter was a very warm and welcoming host, putting Tonya and I at ease when he spotted us on the sidewalk, gawking at his house. After he brought his wife out to join us, we engaged in interesting conversation on a variety of subjects, some concerning the Wolfords, and some not. When Julia took Tonya to explore the side and back yards, I casually asked Anthony what he had done for a living. That was the smartest thing I did all day.

Anthony had been a professional boxing trainer. With my next question I hit the fascination jackpot. I asked him if he had worked with any names I would be familiar with.

Among others, Roberto Duran, Ray Leonard, Joe Frazier. (!!!!!)

All of a sudden, the Wolfords weren’t so interesting anymore.

We talked about boxing until Julia and Tonya returned from the backyard.

While I do not, perhaps Tonya remembers how many times I said on the drive home, “Anthony worked with Joe Frazier!”

Yeah, sure, we accomplished quite a bit on the hunt for the Sharman, Stevens, Persing, and Wolford houses, but meeting Anthony Hunter was definitely the highlight of my day.

Old business

Our last column, featuring the incredible life story of Chuck Sharman, may have appeared to have no relevance to the Gig Harbor or Key peninsulas. Two years ago, when this column began, I noted that from time to time we might stray beyond the borders of the two peninsulas. The Chuck Sharman column was one of those times. But that doesn’t mean the story doesn’t have local ties.

The connections, one of which was left out two weeks ago because the column ran a little … more than a little … way too long, are not rock-solid direct, but are nonetheless real.

As we noted in the story, many Peninsula residents read Chuck Sharman’s comic strip, Salt Chuck, daily in The Tacoma News Tribune. In addition, the USS California, the ship that Chuck Sharman and Bob Mitchell were serving on when it was sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 (technically, it didn’t sink until a couple days after it was damaged), was repaired at the Navy’s shipyard in Bremerton. There is no doubt that Peninsula residents were among the workers who rebuilt the battleship.

With several Spadonis having been employed at the yard during that time, there is a good likelihood that one or more of them worked on the California. But none of them left us a list of the ships they worked on, so we’ll probably never know for certain.

Also, it should be noted that “Panama banana man” was not a phrase exclusive to Chuck Sharman and Bob Mitchell. Other Navy signalmen used it too, even after the war.

Even older business

The April 21, 2025, Gig Harbor Now and Then column noted that Tonya and I had tried to contact a variety of Chuck Sharman’s and Bob Mitchell’s descendants six times, via three paper letters, two Facebook messages, and one email. One of the letters had already been returned as undeliverable. A reader, Kathi Collum, kindly sent me another address to try, which I did with a fourth paper letter. While it wasn’t answered before press time on May 5, it was answered a week after. In the meantime I made an eighth attempt with another email address.

Out of the eight attempts, only two were ultimately successful. One was among the first three letters sent, to Tom Mitchell, Bob Mitchell’s son. He was very accommodating and helpful. The other, later one, was to Mitchell Sharman, Chuck’s oldest son. Like Tom, he was also very accommodating and helpful.

The point of mentioning the eight contact attempts is to show that the two-for-eight success rate, or 25%, is typical. In the April 21 column I had predicted a possible maximum of 33%, and a probable success rate of 0%, so receiving only two responses out of eight was not out of the ordinary. It also shows that this history research business isn’t a casual stroll in the park.

New/old business

With the too-late-for-publication response from Mitch Sharman (not his fault; he called me the same day he received the letter), I now have a lot more information about not only his dad, but several other people in the photos included in the previous column.

Chuck Sharman, as he did with Bob Mitchell, maintained a lifelong friendship with another one of the boys who appeared in two of the photos taken in front of Jean Wolford’s house.

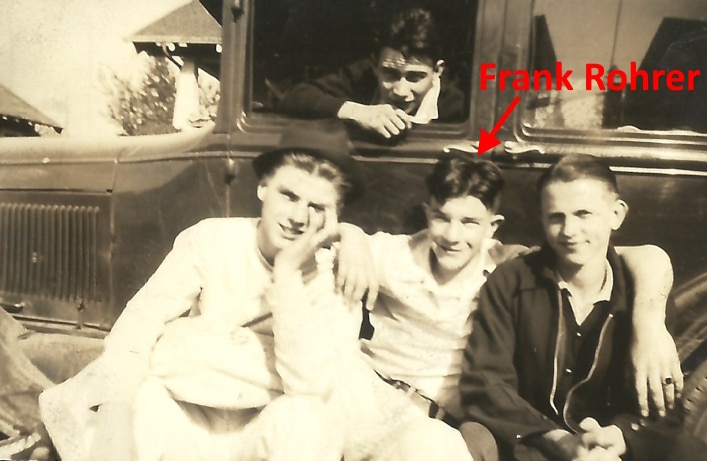

Thanks to Mitch Sharman, we now know that Frank’s last name was Rohrer. Photo provided by Heather Rennaker.

Without seeing the photo first, Mitch Sharman immediately came up with Frank’s last name, Rohrer, when I simply described it to him over the phone, and said I didn’t have a last name for Frank or Bill.

Finally having Frank’s last name, he was pretty easy to find in old newspapers and documents. He too served the entire war in the U.S. Navy. After his discharge, he spent the rest of his long life in the Tacoma area, reaching the age of 90.

Future business

While Chuck Sharman didn’t lose his life during World War 2, as was erroneously reported after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he did lose his girl. Tonya Strickland will tell that aspect of the Behind the Finds story in a future column. She’ll chronicle some really interesting twists in the love lives of several Lincoln High School grads of that era, all concerning people represented in the photographs we found in a Port Orchard second-hand store.

Next time

On June 2 we’ll of course give the answers to today’s questions for the three or four readers who haven’t by then figured them out for themselves.

We’ll also tell what the subsequent column’s subject will be, and it concerns photographs unrelated to the ones found in Port Orchard. With a picture being worth a thousand words, a photo and a half ought to fill the June 16 column. We’ve got a full month to figure out which half.

A parting pair of photos

There are times when stuff is left over from a Gig Harbor Now and Then column (almost every time, actually). Not everything collected for a story fits well. On the other hand, sometimes something totally unrelated is found that’s really interesting, yet unusable because it can’t sustain an entire column on its own. And more often than not, that really interesting something doesn’t fit anywhere else, either.

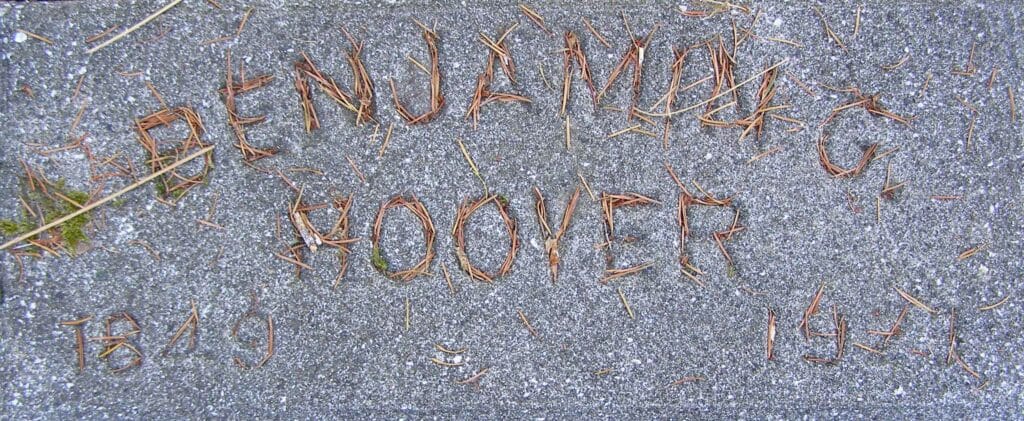

Just such an interesting something was found in the Artondale Cemetery when gathering information and photographs for the March 10, 2025 column, The Homestead Confusion. It was too cool to pass up, so naturally, I photographed it. With today’s column not threatening to be too overly long, now is a perfect time to use it.

Photo by Greg Spadoni

Needles shed by Douglas fir trees in the Artondale Cemetery filled in the letters and numbers carved into the headstone of Benjamin G. Hoover, 1849 – 1923. Not every letter or number is filled perfectly, but overall it’s impressively done.

No doubt there are people who will claim it’s some sort of signal from the afterlife; a kind of concrete Ouija board message from the dearly departed. But I’m going to be a killjoy and assume it was simply gravity at work, aided by wind and rainwater. If the dead really wanted to say something, they could’ve spoken to me while I was there taking pictures. I would’ve responded in some fashion or other. Depending on my mood, what they had to say, and their tone of voice, I may have chatted them up all friendly like, or beat a hasty retreat to my car.

Arthur Constable’s headstone was similarly decorated by the elements.

Photo by Greg Spadoni

As his monument recorded, Arthur Constable died in 1944. No matter the cause of death (for the curious among you, prostate cancer), fate played a cruel trick on him. As with everyone who passed away from 1942 to mid-1945, it’s sad that he never found out how World War 2 turned out. It was the biggest event in world history, and he missed the ending.

Having grown up in England, and with one of his four sons still living there during the war, the outcome would’ve been especially important to him. If he’d have just said something to me while I was taking his headstone’s picture, I could’ve told him what happened.

— Greg Spadoni, May 19, 2025

Greg Spadoni of Olalla has had more access to local history than most life-long residents. During 25 years in road construction working for the Spadoni Brothers, his first cousins, twice removed, he traveled to every corner of the Gig Harbor and Key Peninsulas, taking note of many abandoned buildings, overgrown farms, and roads that no longer had a destination. Through his current association with the Harbor History Museum in Gig Harbor as the unofficial Chief (and only) Assistant to Linda McCowen, the Museum’s primary photo archive volunteer, he regularly studies the area’s largest collection of visual history. Combined with the print history available at the museum and online, he has uncovered countless stories of long-forgotten local people and events.